اليسون لايمن طالبة الماجستير في كلية الشرق الاوسط قي الجامعة تيكساس في اوستن. هي تدرس الشريعة الإسلامية و بعد ذلك هي تحصل على الماجستير، هي تريد تحصل على الدكتوراه، ولكن هي تمكن تعمل في شركة. قبل ما تدرس هنا، هي كانت طالبة في جامعة أركنساس وهي تخصصت في العلوم السياسية و اللغة العربية والعلاقات الدولية. هي تحب أوستين أحياناً وتحب الأكل في أوستن ولكن أشياء أخرى منيحة. في رأيها أحسن مطعم “Suerte” في شارعة ٦ ولكن هي تحب تأكل في “sweetgreen” والأشياء مثل ذلك عندما هي في منطقة الجامعة. هي تتكلم اللغات العربية والإنجليزية فقط وما لغة أخرى. السباحة بالنسبة لها احسن هواية في الصيف. سافرت إلى بلدان كتيرة مثل كولومبيا وبيرو في أمريكا اللاتينية والمانية وإسرائيل أيضاً. تعمل كل يوم في الاسبوع لابها طالبة ومعيدة فدائماً مشغولة. هي مثلك على الا أمك لان عندها أسرة كبيرة (عندها ثلاثة أبناء وأربع بنات!) وعملت كل طفولتها. هي ليس عندها كلب أو قطة الآن ولكن هي تريد كلب ممكن في سنتين.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

الأستاذة ريما

ريما بركات امرأة من أصل سورية. هي لها عائلة كبيرة و هم في سورية. عندما ذهبت على الولاية المتحدة هي ذهبت على ولاية نيويورك. ريما ما تحب نيويورك لأن الطقس كان بارداً جداً كل يوم. هي انتقلت على تكساس و سارت مدرّسة في جامعة تكساس في أوستنً. ريما تحب شغلها كثيراً بسبب الطلاب ممتازين والثقافة مع اللغة. هي حصلت على الماجستير في جامعة تكساس في أوستن. كانت متخصصة في اللغة العربية. ريما تحب تسافر إلى بلاد يتكلمون اللغات الإسباني. أستاذة ريما عندها هوايات كثيرة. تحب الاستماع للموسيقى و تحب الرقص وتلعب “تنس”. بالنسبة للأستاذة ريما أحسن مطعم في أوستين هى مطعم “مزة”. مزة مطعم فيها أكل عربي. المطعم في جنوب اوستن. هي تحب المطعم لأن الناس مبسوطين هناك. بالنسبالها السفر إلى سورية جيد جدا و هي قالت ان احسن بلد هىي سورية. بعد العمل هي تذهب الى موسيقى مناطق في اوستن. تستمع موسيقى عربية. احسن موسيقى في رأيها هي موسيقية فيروز. الأستاذة ريما تحب الطلاب الصف العربي. أيضا في رأيها أحسن طقس هي الطقس البارد و الفصل الربيع.

Biography of Reema Barakat By: Mayy Alsawfta and Hadeed Ahmed

encounters with modernity in the arab world

My aim is to identify three stages of the encounter with modernity as they unfolded in the Arab World over the last two centuries, with the hope of understanding the

driving forces that helped define and redefine Arab concep- tions of the modern. The narrative begins with the intensi- fying interaction with Europe in the early nineteenth cen- tury, which spurred the start of the cosmopolitan phase—a period illustrated primarily by the Levantine culture of the coastal cities of Egypt and the Levant. Conceptions of modernity then largely transitioned to a nationalist phase with its powerful dream of a supranational identity. This Pan-Arabism spread across the Arab World from Morocco to Bahrain, setting the stage for the present day’s phase: a reli- giously-imbued and at the same time a neoliberal capitalism best represented by the rich oil countries of the Arabian Gulf. The sequence is not a neat one; the stages overlap and bleed into each other to create a particularly complex form of Arab modernity unevenly distributed across regional, religious, ethnic, and class fault-lines. The result is there for everyone to see in a contemporary Arab World mired in several civil and sectarian or ethnic wars.

levantine cosmopolitanism

Modern European influence came by sea and seeped slowly into the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. First were the commercial outposts established in many eastern cities by European states. This began with Venice, Genoa, and Aragon in the late Middle Ages, and continued with France, Holland, and Britain from the sixteenth century onwards. While the resident merchants’ interaction with local communities was strictly limited during this period, they nonetheless intro- duced novel European products to local markets—a pro- cess that accelerated considerably in the nineteenth century. After this came the religious missions of the late eighteenth century, and the small schools started in predominantly Christian towns in Palestine and Mount Lebanon. The first Jesuit schools were established in 1770, but these missions grew in number and influence in the second half of the nine- teenth century. They educated a new generation of mostly Christian boys and published Arabic translations of the Old and New Testaments before branching out to more general interest publications.

The military invasion of Egypt led by Napoleon Bona- parte in 1798, and deceptively called the French Expedition, soon followed as the first modern colonial foray into the Arab World. Although it lasted for only three years, it was later exaggeratedly cast as the catalyst for the awakening of the Arab “Orient” to the achievements of European

modernity. This awakening was painfully demonstrated in Egypt through the military superiority of French troops, which easily defeated the Ottomans and the Mamluks in several encounters. It was also perceived in the divergent French administrative organization and legal structures, as well as certain scientific innovations that the French savants occasionally demonstrated to a group of awestruck Egyptian ulama. One of these ulama, Hassan al-‘Attar, went on to write about his admiration of the French scientific experiments he witnessed and his strong belief in the need to modernize the curriculum of al-Azhar, the premier traditional educational institution in Egypt, which direly needed reform and which al-‘Attar would lead as the Grand Imam from 1830 to 1835.

But the idea of modernizing à la franca was not seriously pursued until the 1820s when Mohammad ‘Ali Pasha, the semi-independent and ambitious Viceroy of Egypt (1805– 1848), and the reformist Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II (1789– 1839) almost concurrently concluded that, if they wanted to have a place in the new world order, they would have to adopt the latest European military systems, technological inventions, and managerial and economic methods. To that end, they imported scores of European experts to both Cairo and Istanbul in order to help modernize the army, adminis- tration, and economy, and to later introduce new norms of city planning, hygiene and public health, and industry and commerce.

Modernization e≠orts, however, turned out to be a mixed blessing. While new, disciplined armies were formed, they were defeated in every major confrontation with the European powers that ultimately came to colonize both Egypt and the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire. Education also received a boost: specialized schools were established in the two capitals, and secular curricula and professional training were introduced where none existed before. Slowly, an educated middle class emerged, whose members stated the bureaucracies needed to run the modernizing state. They acquired new tastes and lifestyle habits similar to their European counterparts, even though some conservative customs, such as gender segregation and the status of women generally, proved to be resistant to change. The economies of both states were also transformed with their incorporation into the global trade system. European corporations, which controlled most means of industrial production and distribution in the region, won concessions in the Ottoman Empire and Egypt to modernize infrastructure and open up markets.

As part of this development effort, however, modernizing rulers also had to yield to mounting pressure from the same European imperial powers with which they were eager to catch up and accept the imposition of legislation that under- mined state authority on their own soil. Aptly named the

“Capitulations”, these laws granted extraordinary financial

and legal advantages to foreigners living in their realms and to native minoritarian subjects (mainly Christian Syrians of all denominations, Greeks, Armenians, and Jews) who could claim the protection of a European imperial power. Consequently, a new, ethnically-mixed social group formed that benefitted from the preferential treatment provided by local authorities, and came to dominate the developing one- way trade with industrialized, capitalist Europe—a group that fast began displacing the indigenous mercantile class that had controlled the traditional local economy.

Within a few decades, the cities where this rising new bourgeoisie was concentrated, Smyrna (Izmir), Salonica (Thessaloniki), Istanbul, Alexandria, Cairo, and later Beirut, turned into vibrant cosmopolitan centers of trade, complete with ports, wide avenues, department stores, banks, o∞ce buildings, and all the trappings of modern urban living. These fast developing cities presented not only a new façade of the “Orient,” but also a foothold for Western interests where the two cultures, with their diverse religions, ethnicities, and languages, could meet, interact, and cohabitate in ways that would have been unthinkable in the more ethnically homogenous inland cities.

A new type of individual with the very expressive name “Levantine” emerged in this freewheeling environment. The name came from the French term Levant: the place where the sun rises, which, from Europe’s vantage point, is the

Eastern Mediterranean. The name itself thus imaginatively blends Eastern locale with a European cultural referent to designate the dual ethnic background of its bearer. The emerging Levantine culture embodied this mixed, hybrid identity. It was “Oriental” in its beliefs, customs, forms, and provenance and European in its mores, sensibilities, styles, and ambitions. City-based and urbane, it was multinational, or perhaps even supranational, as it belonged neither to the place of its dwelling nor to that of its cultural aspiration. It stood for the possibility of bringing together people of diverse religious and ethnic backgrounds to live, trade, make money, and be merry together. Gaston Zananiri, a consummate Levantine with a Syrian-Ottoman father and an Italian-Hungarian-Jewish mother, who lived in Alexandria, described this culture as “brilliant, rich and superficial, open to the Mediterranean while closed to Egypt (and presumably the rest of the Arab interior).”

In fact, contrary to Zananiri’s hypothesis, Levantine culture played a major role in defining the era across the Arab interior, especially in Egypt and the Levant. This is partly because the coastal enclaves of Izmir, Smyrna, and to a lesser extent Istanbul and Thessaloniki, lost much of their Levantine character and Levantine inhabitants after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the establish- ment of staunch nationalist governments in Kemalist Turkey and in Greece. In Egypt, however, Levantine culture was

actually energized with the imposition of European colo- nialism at the end of the nineteenth century. A similar e≠ect took place in the interior Levant at the end of the First World War. In both areas, colonial authorities saw the Levantines as indispensable commercial middlemen and interpreters of local mores, as well as exotic reminders of the cultivated refinement they left behind in their colonial metropolises, although they never granted the Levantines the coveted title of “European” or treated them as equals.

The Levantine culture, or at least its outer appearances, did not remain particular to the Levantines themselves. It spread among the native upper class throughout the Arab

World, who found in the Levantine form a suitable arrange- ment that integrated their acquired European outlook and tastes with their conservative and traditional milieu. In the Arab World, a Levantine hybrid culture thus became the prevailing expression of the Westernized “Orientals,” both native and Levantine, who nonetheless remained socially separated by class, religion, and sense of belonging. They could do business with each other, attend the same foreign or missionary schools, use French as their main conversa- tional language, read the same books and newspapers, meet in cafés, clubs, and horse racetracks, frequent the theater and art exhibitions together, shop at the same grands magasins. At the same time, they rarely intermarried or built intimate relationships across social fault-lines, and of course they did

not share the same political views or ties to the European authorities.

Thus, during its heyday in the Arab Mashreq (the coun- tries of the Arab World east of Libya) between 1880 and 1950, the Levantine culture found its expression primarily in an exuberant and cosmopolitan lifestyle, which was lived in beautiful homes, trendy cafés, restaurants, and caba- rets; supported by businesses housed in large o∞ce build- ings; and supplied by fashionable department stores that rivaled those of Paris, the distant trendsetter and archetype. Levantine architecture was cast in a charming eclectic mix of styles that ranged from Neo-Moorish and Neo-Baroque to Art Nouveau and Art Deco and every style in between. Many relics of that age—outdated, exhausted, and abused—still stand across the Mashreq in Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. They are the subject of continuing intellectual and emotional battles among the educated bourgeoisie over their significance and whether they should be preserved from realistic developers, who see them primarily as underutilized real-estate assets devoid of any true meaning or historical relevance to the masses.

Levantine culture never aspired to or managed to penetrate the lower native classes. Take, for instance, the famous book by Lawrence Durrell, The Alexandria Quartet (pub- lished between 1957 and 1960), whose first three volumes are set in cosmopolitan Alexandria at the onset of the Second

World War. Durrell’s inventive modernist narrative is replete with a≠ectionate descriptions of Alexandria seen through the eyes of its European and Levantine inhabitants, who otherwise evince ambivalent notions of belonging and pro- nounced haughtiness towards the “Arabs,” their preferred term for the Egyptian natives. Those natives, of course, constituted the vast majority of the city’s residents despite their minimal role in the lives of the Quartet’s protagonists, save as servants and background décor, a function they also occupied in real life.

Or consider the famous Alexandria: A History and a Guide (1922) that E.M. Forster wrote while stationed in Egypt during the First World War. The book is deemed among the best modernist literary presentations of a city, and consists of an exhaustively researched and idiosyncratically structured history followed by a series of visits executed mostly by tramway excursions to the city’s important sites. But what history and what sites? Forster spends much time and e≠ort recounting Ptolemaic and early Christian Alexandria between the third century bce and the sixth century ce, reimagining its monuments and contextualizing them by quoting at lengths from Classical authors and European literary figures. He then casually skips over more than ten centuries of Islamic history, which he calls “years of silence,” before resuming the narrative in the sixteenth century to culminate with colonial Alexandria and its cosmopolitan

present, literally mapped onto its presumed Hellenistic glorious past. In other words, Forster not only ignores the native inhabitants, he actually erases their past from the city’s history and expunges their still standing architectural heritage from its topography. In a nutshell, Forster denies the Egyptian Alexandrians any claim over their city, which he sees as the exclusive domain of its Western or Levantine citizens.

There were exceptions to this narrative, most nota- bly Beirut, which was a city that came relatively late to its Levantine phase. It is a city whose bounty of cosmopoli- tanism extended to all its inhabitants: natives, foreigners, Levantines, and Arab émigrés. Beirut benefited in particu- lar from its inclusive, some would say lax, approach to the notion of belonging, as it built its mid-twentieth-century reputation as the “Paris of the East.” It became a hub of com- merce, pleasure tourism, and espionage, and the prime ref- uge for Arab captains of industry, as well as intellectual and political dissidents fleeing other Arab countries that were succumbing one by one to autocratic, ideologically rigid military regimes. These developments made Beirut the unexpected center of Arab culture with its relatively free press, robust American University steeped in the liberal arts tradition, thriving theater, music, and art scene, and literary cafés where expatriate Arab intellectuals of all political colors met, debated, and dreamt of a better future.

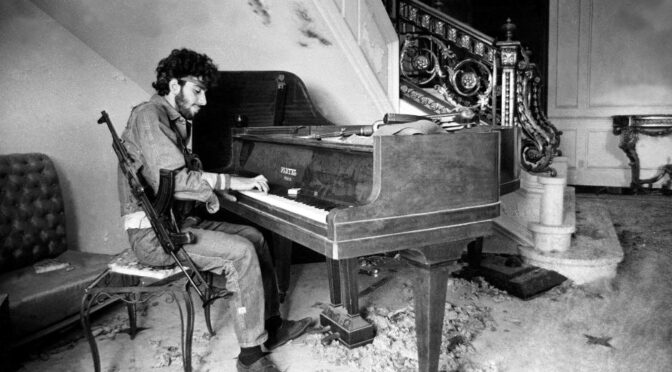

Beirut tragically lost that status during its brutal fifteen- year civil war (1975–1990), which destroyed both its cosmo- politan spirit and the favorite hangouts of its urban maze. Somewhat anachronistically, and despite the turmoil sur- rounding it, Beirut has been recently trying to recreate that vanished image with all its nostalgic accouterments from cafés to art-galleries to cabarets, especially in the downtown Solidere reconstruction project. But the rebuilding, some- times done from scratch and exquisitely attentive to authen- tic architectural details, is marred by the leftover politics of the civil war and a contrived neoliberal funding scheme tinged by the tastes of the desert and the lure of black gold. It has yet to recover the allure of the cosmopolitanism of old Beirut.

Levantine cosmopolitanism understandably retreated with the end of colonialism, its main manipulator, bene- factor, and protector. It was dealt a second blow with the violent splitting of Palestine and the creation of Israel as a Jewish state in 1948. The dispossessed Palestinians took ref- uge in the surrounding Arab countries, while many of the Levantines, including Iraqi and Egyptian Jews, moved to Israel or Europe. They left behind abandoned businesses, empty palaces, deserted cafés, and a handful of stragglers that largely withdrew from public life to live with the reminders of their former glitzy days. In response to these changes, a few turned their sense of loss and nostalgia into

art. The Armenian-Egyptian photographer Van Leo (born Levon Boyadjian, 1921–2002), for example, celebrated the age that just passed in polished, poignantly black and white self-portraits fashioned after stylish Western models and in images of celebrities resonant of the carefree and chic life- style of yesteryears.

The most nostalgic Levantine artist was perhaps the late director Youssef Chahine (1926–2008), whose series of films on Alexandria, Alexandria, Why? (1978), Adieu Bonaparte (1985), and Alexandria Again and Again (1989), tell the story of his native city from the perspective of the unapologetically Westernized cosmopolitan yet Egyptian-to-the-core gentleman that he was. In Alexandria, Why? and Alexandria

Again and Again he weaves his thinly-veiled autobiographical narrative around the glamor, tolerance, and open-mindedness that marked the city of his youth in contrast to the narrow-minded, conservative, and ill-mannered way of life that he saw rising around him. He criticized that hardening of values directly in his later film, al-Masir (The Destiny, 1997). That movie was set in Ibn Rushd’s Cordoba of the eleventh century but dealt with the authoritarianism, censorship, fundamentalism, and violence of the contemporary Arab World; a film for which he was later severely attacked by religious conservatives.

arab nationalism

The end of colonialism bequeathed center stage to another form of modernity in the Arab World: nationalism. The lib- eration movements and political parties that took over from the withdrawing colonial powers rushed in to shape their countries’ sovereign identity. New powerful concepts, such as historical identity, authenticity, and the recovery of Arab cultural roots, rose to the pinnacle of political and public interest. Concurrently, the center of gravity in urban life shifted from the cities of the seacoast, open to the West and its tempting influence, towards the grand cities of the inte- rior, Cairo, Damascus, and Baghdad, the old capitals of Arab golden ages. Arabic supplanted the cacophony of languages spoken by the Levantines, and Arab history and culture became both the focus of the intelligentsia and the foun- dations of the state’s cultural and educational policies. This focus on Arab identity would also receive a significant boost from the more radical ideals brandished by the regimes in Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Algeria, and later Libya and the Sudan, that came to power through military coups during the 1950s and 1960s.

Lacking some of the crucial components of legitimate governments, the military regimes overcompensated with an exaggerated reliance on the politics of class and identity.

While all of them pursued a statist agenda bedecked with

the trappings of nationalism, most also simultaneously sub- scribed to a mixture of supranationalism, a pan-Arabism combined with a hollowed form of state socialism. Modeled on badly translated French and German theoretical models, and equipped with its own historical and territorial claims and symbolic programs, political Arab nationalism peaked in the 1960s. It particular, it found its fulfillment in Egypt’s charismatic leader Gamal Abd al-Nasir who led a hastily con- structed United Arab Republic between Egypt and Syria that lasted from 1958 to 1961. In the beginning, the euphoria of unity dominated the public sphere; millions sang with Abdel Halim Hafez, al-‘andalib al-asmar (the “Black Nightingale”) of Egypt, watani habibi, al-watan al-akbar (my beloved country, the great country) in anticipation of the coming full Arab unity. Slowly many Syrians came to feel that their country had been shortchanged and they eventually backed another military coup that broke up the union with Egypt.

Despite this debacle, however, Arab unity remained for a generation a dream of the masses and a political inter- est pursued by the so-called progressive military regimes, especially among those who were looking to legitimize their authority. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, a series of hastily-conceived unification attempts alternately involved Syria, Egypt, Iraq, Yemen, Sudan, Libya, and Algeria. All of these were short-lived, and left behind only a plethora of modified flags that ri≠ed on the themes of the eagle and the

star against the backdrop of the alleged colors of Arabism, black, white, red, and green.

These same regimes adopted ambitious socialist modern- ization programs, complete with land reforms, socialization of basic services, and grand public projects that were meant to herald the new age of progress. The socialist framework was predicated on a modern working class that was defined and celebrated through grandiose, poorly conceived, and hastily implemented agricultural, industrial, educational, and infrastructural projects. This changed the face of Arab cities, which rapidly acquired large governmental complexes, whole new administrative and industrial districts, a variety of public housing, and universities and schools. This formal architectural modernism, sometimes softened by symbolic references to history or gestures toward climate and site, apparently rested on the assumption that modernist building projects could stand-in for expressions of cultural modernity.

Progressive modernization remained an incomplete project in the face of inherited or created geographic, historical, and social contradictions. It further suffered from corruption, autocratic mismanagement, incompetence, and ignorant naïveté, compounded by the protracted yet irresolute conflict with Israel and the overwhelmingly interventionist Cold War politics that drowned the region in endless political scheming. On top of this, the startling defeat of Egypt,

Syria, and Jordan in the 1967 war with Israel spelled the end of the grand plan of building modern states that would lead to a unified and triumphant Arab nation. A mood of defeated melancholy and wounded ego pervaded the culture and the arts everywhere in the Arab World. There were some who tried to respond to this defeat with measured calls for ideological and intellectual revisions to how the Arab World should approach modernity. They included thinkers such as Sadik Jalal al-Azm, author of Al-Nakd al-Dhati Ba’da al-Hazima (Self-Criticism After the Defeat) (1968) and Naqd al-Fikr al-Dini (Critique of Religious Thought) (1969). It also included artists such as Youssef Chahine, who blamed endemic corruption for defeat in his iconic film The Sparrow (1972), and Saadallah Wannous, whose play Haflat Samar min Ajl Khamsa Huzayran (Evening Party for the Fifth of June) strongly indicted the entire Arab political system. These intellectuals, however, were all strongly rebuked, and some- times prosecuted, by regimes that adamantly refused to acknowledge their role in the Great Defeat and that held on to the belief that the territories would someday be recovered after the (rhetorically downgraded) al-Naksa (the Setback).

The hope of Arab nationalism was soon rekindled by a newly-invigorated Palestinian Liberation Organization (plo). The plo provided an opportunity for the Arab world to commit to not only a revolutionary liberation movement, but also an entire project of building Palestinian national

[18]culture complete with art, literature, and the scholarship of remembrance. Yet these hopes were repeatedly dashed: first by the Black September War between Jordan and the plo in 1970, then by the excruciating Lebanese Civil War in 1975, and finally the October War of 1973 between the Arabs and Israelis. This final encounter resulted in the Camp David Accords of 1978 between the Egyptians and Israelis, which broke any remaining semblance of Arab cohesion. The death of Abdel-Nasser in September 1970, possibly out of exhaus- tion at trying to broker a deal between the plo and King Hussein of Jordan, darkly presaged the closing of a chapter in modern Arab history.

The 1970s and 1980s saw an economic-political reversal in most Arab republics with the dismantling of the falter- ing socialist experiments of the 1950s and 1960s and their gradual replacement with a statist form of crony capital- ism. In Egypt, this process was initiated by Anwar al-Sadat, Abdel-Nasser’s successor in Egypt, and given the mislead- ingly liberal name Infitah (opening up). The net e≠ect of this project was deepening economic inequality in the coun- try with little political gain. Similar, though more carefully disguised, economic reorientations followed in ostensibly Arab socialist or quasi-socialist countries, such as Syria, Iraq,

Yemen, Libya, and Algeria. In these countries, the military regimes hardened into tyrannical dictatorships devoid of any political pretensions, whose sole purpose was to stay in

[19]power and to enrich their narrow bases of supporters. Most of these countries experienced acute problems of urban and rural degradation, infrastructural exhaustion, demographic explosion, and socioeconomic inequality. In the 1980s and 1990s, despondent rural migration flooded the cities. The cities swelled uncontrollably, and at an unprecedented rate, to house the bursting poor population in peripheral, min- imally zoned, and badly serviced areas that were strangu- lating the old urban cores. These dismal living conditions, su≠ered by the vast majority of Arab urban dwellers, were at the root of various violent riots over the years, and eventually culminated in the revolts of the Arab Spring, which unfor- tunately devolved into the exceedingly destructive armed conflicts a±icting most of the countries that revolted against their dictators in 2011.

political islam and capital

The revolts of the Arab World did not erupt until the begin- ning of the second decade of the twenty-first century and, as a result, the Arab masses had to endure their ageing and hardening dictatorships even after the end of the twentieth century. During this period, Arab nationalism waned as the premier rallying call for the region and a di≠erent and pas- sionate political discourse that saw “Islam” as a more truthful framer of identity rose in its place. Of course, the politicization of religion was not new. It had been operative since at least

[20]March 1928 when, in Isma‘iliyya, Egypt, Hassan al-Banna founded the Muslim Brotherhood, by some accounts, the intellectual and organizational fountainhead from which most later Islamic political parties evolved. These more recent movements, however, developed in radically diver- gent contexts that molded both their outlook and their modi operandi. In the left-leaning military regimes, where Pan- Arabism was the dominant political ideology, political Islam existed as an underground current that emerged on the surface in the 1980s. On the other hand, in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Sheikhdoms, where national image was already based on Islamic identity, a tamed and heavily controlled form of political Islam thrived as state dogma. It was, however, only after two momentous events in 1979—the triumph of the Iranian Islamic Revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan—that political Islam galvanized as a response to the failure of Pan-Arabism to address the contemporary challenges of Israeli aggression, foreign interference, eco- nomic corruption, and moral decadence.

Political Islam has sometimes taken a violent turn. Part of this violent response is inspired by radical Islamist think- ers like Sayyid Qutb. In his manifesto, Ma‘alim fi-l Tariq (Milestones) (1964), Qutb advocates for jihad against jahili- yya (pre-Islamic ignorance or secular authorities, whether Islamic or Western) as the most reliable means of recovering

[21]the true Islamic polity that recognizes only God’s sovereignty (hakimiyya). Contemporary militant, and at times exceed- ingly violent, Islamist organizations have taken up this fight against what they perceive as secular and Western-controlled Arab regimes. Some use stealthy methods, such as assassination and suicide bombing, to spread terror. Others wage military campaigns against regular Arab armies or foreign forces. Their political programs are often rather ambiguous but their ultimate goal is to re-establish what they perceive as a more authentic Islamic form of governance, drawn from a strict and literalist reading of scriptures, to rule over al-Umma (the Islamic nation). The Islamic State, currently expanding in Iraq and Syria despite the counteroffensive of an international coalition, is but the most successful manifestation of that movement to date.

This badly understood movement of political Islam is still evolving. Its byproducts have been spreading since the early 1980s under the watchful eye of the brutal, yet per- haps complacent, regimes in the form of vestmental and behavioral modifications, such as veiling among women and growing beards among men; louder and more defiant presence of religious practices and symbols in the public space; and more vocal, and sometimes very violent, objec- tions to all cultural and social practices perceived as “secular” or as modern Western imports. Despite its apparent ascen- dancy, political Islam has had surprisingly little influence

[22]on creative culture, which remains largely nationalist and Western-influenced. Aside from crude proselytization through populist web portals, publications, and television stations with their tele-Islamists, political Islam has not penetrated the arts, literature, or media in general in any

significant way, save for the few and far between “awaken- ings” of actors or singers and their subsequent retirement or conversion to religiously-sanctioned practices. Cat Stevens, a.k.a. Yusuf Islam, is a famous international example who restricted his singing after his conversion to religious hymns with no musical accompaniment. Admittedly, he seems to be coming back nowadays. Another, more militant example is Fadl Shaker who was a popular Lebanese singer until his withdrawal from public life in 2012, when he joined the extremist Salafi leader Ahmad al-Asir in his botched confrontation with the Lebanese army in Sidon.

By contrast, another group that has wielded a similar, but less radical, view of Islam as a frame for identity is the elite of the exceedingly rich states of the Gulf region. Decidedly comfortable with the nation-state framework and its modern structures, this leading political and economic group has had a tremendous impact on decisive cultural, social, financial, and urban changes in the Arab World in recent years. Having laid on the edge of the desert, away from the centers of Arabic culture, and, with the exception of Saudi Arabia and Oman, having not achieved independence until

[23]the 1960s and even 1970s, the people of the Gulf had no role in the early development of modern Arab culture. This situation began to change shortly after the discovery of oil in the 1940s and, more dramatically, after the 1974 oil price surge when these poor countries became super-rich. The empowerment occasioned by the huge financial surplus accumulated from oil, the deeply religious and conservative outlook of the Gulf elite, and the fervent desire for politi- cal and cultural prominence in the region, created a great demand for a contemporary and dynamic yet recognizable Islamic identity, which found its most visible expressions in lifestyle and urban forms.

Developments on the regional and world stage at the end of the twentieth century intensified the already potent blend of conservatism and capital in the makeup of the Arabian Gulf states. First was the foolish and ill-fated invasion of Kuwait by Saddam Hussein in 1990, which only further deteriorated the trust between Arab countries. The attempt by the United States-led international coalition to repel Saddam eventually resulted in the devastation of Iraq, the strongest Arab nationalist state leftover from an earlier age, and the strengthened United States hegemony over the secu- rity and economies of the Gulf countries. Internationally, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the dissolution of its socialist model further emboldened an already rampant capitalism to extend its reach all over the globe. The Arabian

[24]Gulf, awash in cash, relatively underexploited, and eager to diversify and secure its sources of income presented the perfect combination of willing lucrative market and loaded potential partner to global capitalism.

Dubai, with its entrepreneurial spirit, unrestrained laissez-faire economy, and aggressive pursuit of investments, led the way. The entire city, from desert to coast, became the world’s most phenomenal real-estate development with gargantuan business parks and malls, luxury residences and hotels, and showy entertainment complexes. In this make-believe setting, the “utopian capitalist city,” as writer Mike Davis called it, emerged as a branding instrument and spectacular wrapping for new lavish enterprises, which broke all previous norms of size, form, function, fantasy, and, often, economic purpose and urban vision. Yet, the fierce pursuit of extravagant projects aimed at the global wealthy spread uncontrollably to other Arabian Gulf cities. Eventually, they all acquired super-slick high-rises tower- ing over their skylines; lavish shopping malls with trendy boutiques; investment banks, stock markets, and venture capitalists looking for investment opportunities; outposts of “American” universities seeking to benefit from the superior reputation of their namesakes; cultural monuments that they hope will put them on the world travel map; satellite channels and print and online publications that have regional and even global aspirations; and enormous state

[25]mosques exclaiming their Islamic and deeply conservative identity.

Although the implementation of huge developments in the Arabian cities during the last twenty years has brought an influx of people of myriad nationalities, ethnicities, and religions that vastly surpassed the population of native inhabitants, no real cosmopolitan urban society has materialized. Instead, separate communities live side by side in their distinct districts with little interaction and cross-fertilization, and with a clear hierarchy that converts the pre-modern tribal order into a contemporary polity. The ruling families monopolize all political power, granting the native citizenry extraordinary economic and civil services while denying expatriate communities rights to much of their city. The professional expatriates, who come mostly from the West and some Arab countries such as Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, and Palestine, enjoy considerable financial advantages and some minor civic rights, but they have no legal way to achieve true citizenship. The masses of poor laborers—the South and Southeast Asians who constitute the majority of the Arabian cities’ residents—are deprived of even the most basic civil rights. They are discriminated against, poorly paid, offered no social security or access to due process, and crowded in ill-kempt camps or dilapidated rental neighborhoods away from the city. Despite recent signs of change in some of these states, yielding to pressure from international human rights

[26]organizations, the grave problems that this situation has created have yet to be properly addressed and resolved.

The harsh e≠ects of the extreme conditions of real estate capitalism, however, are felt more acutely in the older and poorer Arab cities that cannot sustain this kind of financial and urban extravaganza. Many were nonetheless invaded by Dubai-style developments that accelerated physical decay by cutting through their urban fabric, siphoned funds away from their public services, and deepened the discrepancy between their haves and have-nots. But the most alarming consequence of this relentless manipulation of capital is the fading of the civic qualities that were slowly acquired over the last two centuries, and their replacement by a double- headed market-driven commodification process, which has split the city into two extremes. On one end, the old, poor quarters are robbed of the last vestiges of urban life and turned into run-down contiguous village-like neighbor- hoods cut o≠ from the authorities and the law and left to live by their own informal and traditional codes. On the other end, the new rich suburbs acquire a consumerist and glo- balized identity that has no local feel or sense of belonging.

When the 2011 revolts of the Arab Spring erupted, they were partially a response to these conditions. The activists who initiated the protests aimed at nothing less than to redress the perversion that had for more than half a century impressed upon their people the obligation to sacrifice their

[27]civil rights for their repeatedly hijacked national integrity. They were in fact seeking to restore to their countries the principle of citizenship as the basis of belonging and the ideal of equality under the rule of law, both of which are of

course modern concepts. But things did not go as hoped for and the promising Arab Spring degenerated into a patch- work of gloomy prospects. Why did this happen?

The most obvious answer is that the long-lived dicta- torial regimes have so severely damaged the fiber of their societies that it will take a long time to fully restore civic virtues, assuming that the new rising forces have the will and the desire to repair to a civic political system. But, as I have tried to show, the roots of the problem go farther back. They are to be found in the particularly complex history of the uneven engagement with various aspects of modernity in the last two centuries. This incomplete process has fostered acute discrepancies in identity, ideology, and wealth among the mosaic of sects, ethnicities, tribes, and civic groups that share the same space and relentlessly compete over the right to define it. Their fighting has now come to the open in a very vicious and devastating manner. At this moment, the buoyant beginning of the Arab Spring in 2011 appears like a blip in a long and very hot summer.

طلاب برنامج اللغة العربية في جامعة تكساس نرغب غالباً في الحصول على تجارب أكثر مع الثقافة العربية وممارستها خارج الصف. ومن الطرق الجيدة للحصول عليها هي الالتحاق بالأندية والمنظمات الموجودة في الجامعة. وبحثت على بعض الأندية وتحدثت مع المنظمين من أجل استكشافها ومشاركتها معكم في هذه المقالة.

طلاب برنامج اللغة العربية في جامعة تكساس نرغب غالباً في الحصول على تجارب أكثر مع الثقافة العربية وممارستها خارج الصف. ومن الطرق الجيدة للحصول عليها هي الالتحاق بالأندية والمنظمات الموجودة في الجامعة. وبحثت على بعض الأندية وتحدثت مع المنظمين من أجل استكشافها ومشاركتها معكم في هذه المقالة.