This question was posed in a blog post on The Economist web site on September 23. Why does the question matter? It matters because it forces us to think about the nature of globalization, its history, and its interpretation. And it forces us to address the question of whether globalization has benefited humanity over time. In that sense it is important to understand whether globalization started in Antiquity, around 1500, in the 19th century, or in the 1980s, as arguments can be made for all scenarios.

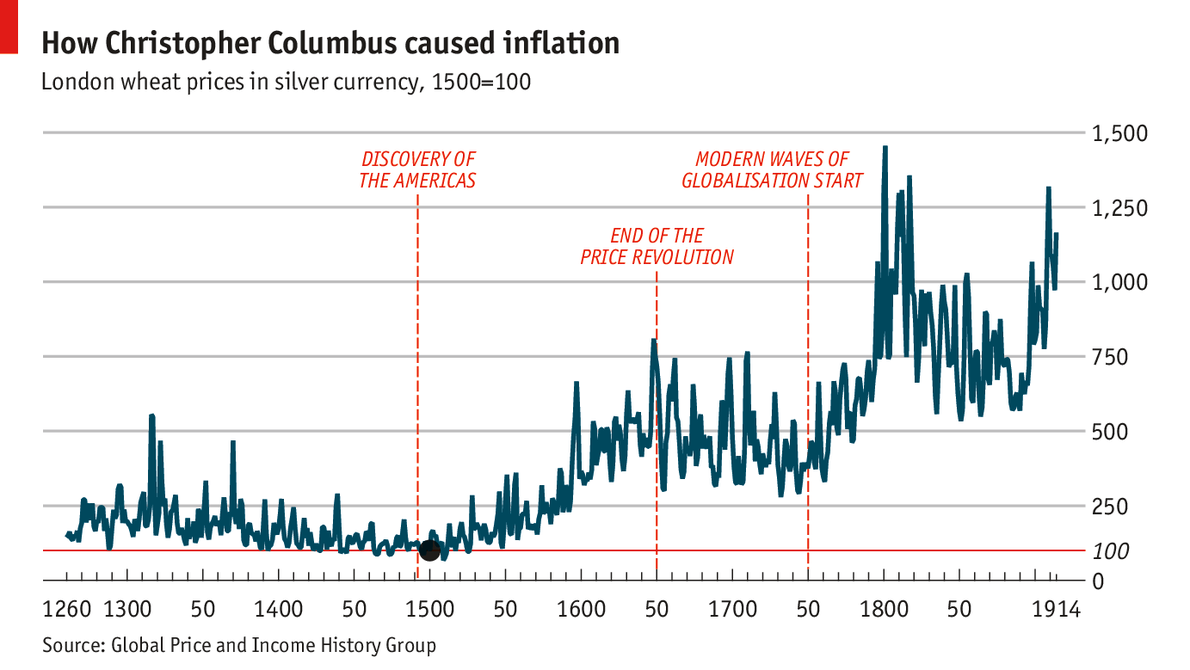

Economists like to connect globalization with a convergence and integration of markets, enhanced by a progressing division of labor and expanding trade systems. The great European discoveries around 1500 thus must be seen as a major incubator for globalization. Already Adam Smith argued that the influx of great amounts of silver from mines in Mexico and Bolivia in the 16th century profoundly affected the markets in Europe by dramatically lowering the price of silver–to which the value of European currencies was pegged–while accelerating inflation. Inflation only slowed around 1650, so the theory goes, “when the price of silver fell to such a low level that it was no longer profitable to import it from the Americas.”

The fact is that Europe suffered from serious inflation between 1500 and 1650 which had a destabilizing effect on European societies. Inflation was real, and it was feared. In church hymns of the time, inflation joined illness, hunger, disorder, celestial events, and the Turks as the most serious ills of the time that required God’s assistance. But did Columbus cause inflation?

While the story of American silver is a compelling one, there are a number of destabilizing factors after 1500 that contributed to inflation: the Protestant Reform, the transformation of a feudal society into a mercantilist one, the rapid growth of urban production with rising wages, the Little Ice Age, and the Turkish threat, to name just a few. Then there was the demographic collapse created by the arrival of the plague around 1350 which caused low prices, and the rapid rise of the population starting in the late 15th century which caused a rise in price levels and promoted a rapid expansion of the European trade system. Inflation was also driven by the Thirty Years War (1618-48) which created both shortages and high demand for weapons and provisions for soldiers. The 1648 Peace of Westphalia ended the high demand, and coupled with a massive population loss in the Empire it also ended inflationary pressures.

But there is a larger point to be made. Globalization is a way of thinking about the world and the role of the human in it. Around 1500, the way humans thought about space and the way they related to it changed profoundly. The earth now was thought of as a sphere that could be traveled on endlessly, the universe became infinite, and art marked the centrality of spatial relations through Leonardo’s innovation of the perspective. It is in this context that Columbus’s westward travels to Asia and Vasco de Gama’s travels around Africa and across the Indian Ocean became thinkable. So globalization reflects a state of mind which allows humans to see the world as a whole, to understand spatial relations, to make connections between its parts, and to act upon this insight. The transformation from the old T-O world map, printed as late as 1475, and the Waldseemüller world map of 1507 that first marks “America” indicates this intellectual leap.

Vasco de Gama may have stopped at this protected natural harbor on Mozambique Island in 1498. The Portuguese built their first fort here in 1507.

The second element in this globalization story is competition. It is no accident that Columbus and Vasco de Gama ventured out almost simultaneously to find a sea route to Asia. Both Spain and Portugal were in an open competition to find a commercially viable route to Asia to enhance their trade in high-value goods such as silk and spices. While quickly seizing the opportunities the newly discovered continent offered, the Spanish for three decades were feverishly looking for navigable passages through or around it.

The third element was that the discoveries were driven by commerce, not by sheer curiosity. As opening a sea route to Asia had great economic promise, many merchants and investors financed expeditions to lands unknown. Voyages of discovery were financed by private venture capital under license from the Spanish and Portuguese crowns to a significant degree. Santo Domingo, the first Spanish hub in the Americas, became a city with stone buildings teeming with investors, entrepreneurs and adventurers within a decade of Columbus’s arrival. From there, the new Atlantic trade system evolved with breathtaking speed–which included mining and plantation operations in the Americas, the Transatlantic slave trade, and an intensifying trade with Asia. But it is the intellectual leap of seeing the world holistically which is the true moment of globalization, the evolving system of global trade just being its logical outgrowth.

The Calle de las Damas in Santo Domingo in 1502 became the first paved road built by the Spanish in the Americas, just 10 years after Columbus first arrived here. These stone buildings were built as investment properties around the same time. One tenant was Hernán Cortés.