Mexico’s Law Enforcement Challenge: The Case Study of Ciudad Juarez

By

Ricardo Ainslie, Ph.D.

Introduction

With respect to Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs), there is a long-standing history of corruption and collusion within Mexican law enforcement that goes back to the 1970s when Rafael Aguilar, the head of the Federal Security Directorate (DFS by it’s Mexican acronym) in the state of Chihuahua, became one of the founders of the Juarez Cartel. Until his death in 1997, Amado Carrillo Fuentes, who rose to take over the Juarez Cartel, was known to have highly placed contacts within Mexican law enforcement, beginning with the Mexican Federal Judicial Police, which controlled the highways and the airports, to state and municipal police forces which he controlled outright in the states that were of importance to the Juarez Cartel’s operations. The same is true of the other powerful Mexican drug cartels – historically they have had a firm grip on the law enforcement agencies in the states where they operate and, at times, at the federal level as well. For this reason, there have been many efforts to clean up Mexico’s various police forces, and most have met with mixed results at best. Yet, effectively combating DTOs requires effective law enforcement.

Mexico’s president, Felipe Calderón, launched the war on drugs in December of 2006 immediately upon assuming office. It was well established at the time that Mexico’s five most important cartels (the Sinaloa/Pacifico Cartel, Juarez Cartel, Tijuana Cartel, Gulf Cartel, and La Familia) effectively controlled substantial swaths of Mexican territory. In the view of the Mexican government, the cartels had become more than a crime problem, they had become a threat to the Mexican state.[1] It is clear that the Mexican government believed it had reached the point of no return. Either they took on the DTOs or they lost control of significant areas within many states. It was already established that municipal and state ministerial police forces in states like Chihuahua, Sinaloa, Baja California, Tamaulipas, Sonora, and Michoacán, to name some of the more important ones, were for all intents and purposes already under the control of the DTOs. Officers who posed obstacles to the cartels’ interests were routinely executed. Police officers who were not colluding with the cartels were threatened and intimidated into silence and thus effectively neutralized. These facts on the ground made it evident that the Mexican government had few law enforcement tools at its disposal for achieving the task it had laid out for itself.

The Calderón government embarked on a two-pronged strategy[2]. First, it would use the Mexican army (a force of approximately 240,000 troops) to carry its campaign into the areas where the Mexican drug cartels had the strongest footholds. Second, it would embark on a massive effort to re-shape and build the force that would become the Mexican Federal Police. It was believed that the latter force could be both the spearhead in the efforts against the DTOs and, eventually, become the model for cleaning up and reforming state and local police forces. However, at the beginning of the Calderón administration there were but 6500 Federal Preventive Police[3] (the Federal Preventive Police became the Federal Police in 2009 when the role of the Federal Preventive Police was expanded to include investigation and analysis, however, for purposes of clarity of exposition, I use “Federal Police” throughout the rest of this contribution since the PFP and the PF are one and the same organization).[4] In the interim, the Mexican government deployed approximately 45,000 troops to the nation’s most violent cities and states. In other words, the Mexican military became the boots on the ground as a short-term strategy until the Federal Police could be recruited, trained, and deployed.

Ciudad Juarez

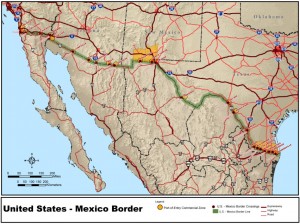

Throughout 2007, Mexican cartel violence was centered in places like Michoacán, Baja California (Tijuana), and Tamaulipas (Nuevo Laredo and Matamoros). Although other communities were affected to a lesser extent, these were the cities where the greatest violence was taking place. Ciudad Juarez, across the border from El Paso, Texas, had 301 executions that year[5]. Even though the number was record setting, the Mexican government’s attention was on places like Michoacán (where there were dramatic beheadings and grenade attacks against the general population), Nuevo Laredo (where municipal police ambushed a column of Federal Police arriving in the city after the execution of the local police chief), and Tijuana (where violence had been chronic).

In December of 2007, federal intelligence officials notified the mayor of Ciudad Juarez, José Reyes Ferriz, that they had evidence that the Sinaloa Cartel was poised to launch a major effort to wrest control of the city (and its lucrative smuggling route into El Paso and points beyond in the United States) from the Juarez Cartel.[6] That war started in January of 2008.

Municipal Police Collusion with Juarez Cartel

Perhaps the most infamous example of corruption within the Juarez Municipal Police is the fact that in January of 2008 the force’s former Director of Operations, Saulo Reyes, was arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents in El Paso for smuggling nearly a ton of marijuana and attempting to bribe a Federal agent. Reyes had only left the Juarez Municipal Police (where he was the most important official after the chief of police) three months prior, when the term of then-mayor Hector Murguía expired.[7] Murguía had appointed Reyes to the sensitive law enforcement post despite significant opposition from people who were concerned about Reyes’ alleged links to the Juarez Cartel.

In the spring of 2008, as the war between the Sinaloa Cartel and the Juarez Cartel erupted, the Juarez Municipal Police became a highly contested strategic asset that each of the cartels sought to control. The result was the execution of scores of municipal and state police officers the spring and summer of 2008 (see Table 1).

Table 1: Police Executions in Juarez 2007-2010[8]

Juarez Municipal Police Other Police Total Police Killed

2007 4 7 11

2008 38 33 71

2009 25 42 67

2010 67 82 149

134 164 298

The execution of police officers was a symptom of the conflict that was now raging in the city between the Sinaloa and the Juarez Cartels. The clearest indication of this is a poster that was left at the Monument to Fallen Police in Ciudad Juarez at the end of January 2008 in which the Sinaloa Cartel listed the names of five Municipal Police officers who had been assassinated. It labeled those five officers as “Those who did not believe.” Below that list was a second list of seventeen names of current Juarez Municipal Police Officers under the heading “For those who still do not believe.” The list was an obvious death threat against those officers. The prevailing wisdom is that the officers on the “still do not believe” list were either officers aligned with the Juarez Cartel or officers who had resisted Sinaloa Cartel efforts to enlist them. Within a year, all of the officers on the “Still do not believe” list were either dead or they had resigned from the police force.

In May 2008, ten police were executed, including one policeman who was decapitated and left with a new list of police who were targeted for execution. One of the executed was a commander of an elite strike force within the Municipal Police who was killed in his office, evidence that the killers were operating within the police department. By June and July 2008 there was massive panic within the Juarez Municipal Police, leading to work stoppages. Relatedly, the city was victimized by the outbreak of a serious crime wave.

The budget for the Juarez Municipal Police was approximately 60 million dollars a year.[9] Mayor José Reyes Ferriz estimated that the cost of neutralizing the entire force cost the cartels approximately $300,000 dollars. “For $50,000 pesos a month (less than $5,000 dollars) they could own a commander, and that person controlled what went on within his area. Operations people they could buy for anywhere from $20,000 to $50,000 pesos a month, depending on what they did.”[10] An interview with a Juarez Cartel sicario (hit man) similarly describes the mechanisms via which the Juarez Cartel controlled state and municipal police forces. The sicario worked within the Chihuahua state Ministerial Police. In his training class, there were 200 recruits, of which he alleged that one-quarter were employed by the cartel[11]. Whether or not the specific figures are accurate, the interview supports the idea that the cartels do not need to own all of the police, just key people who are strategically placed.

Operación Conjunto Chihuahua

In March of 2008, the Mexican government launched Operación Conjunto Chihuahua, in an effort to stem the violence in Ciudad Juarez. 2,500 army troops were sent to support law enforcement efforts. Initially, the army refused to patrol with the Municipal Police because of the extensive penetration of the police by the cartels. An additional problem was that the army troops, most of whom were from central and southern Mexico, did not know their way around Juarez’ neighborhoods (many of which, because they were established as un-regulated settlements, are labyrinth-like patchworks), a fact that complicated their response to criminal activity and emergencies. Eventually, this was addressed by having a single Municipal Police officer attached to each military patrol.

A systematic attempt to clean up the 1500 member Municipal Police force was launched at the same time, with the Federal Police administering a battery of tests, known as “Confidence Tests,” that included drug testing, polygraphs, voice biometrics, personality tests, background checks, and finger prints that were checked on the national data base known as Plataforma Mexico[12]. The testing resulted in the firing of approximately 400 officers in October of 2008. Another 70 had resigned prior to the results and another 17 had been fired in the preceding six months. Adding the 38 officers that were assassinated in 2008, over a third of the Juarez Municipal Police force was fired, resigned, or killed in the course of 2008.

The police who remained were sent to a military-style boot camp at a Chihuahua military installation called Santa Gertrudis. There, the received training in the use of assault weapons (at that juncture in Mexico no other state or municipal police force was equipped with assault weapons or trained in their use). In addition, police chief Roberto Orduña, a former army major, and the mayor set out to recruit and train a new police force. They travelled to military installations in Mexican states as far away as Oaxaca and Veracruz in search of new recruits who had a military background because it was thought that they might be more disciplined and more able to resist threats and corruption than local civilian recruits would be, especially given the extensive influence of the cartels and their gangs in the Juarez neighborhoods. However, the continued violence led to a massive attempt to recruit and train a force, mostly recruited in Juarez, that was called the “New Police.” In September of 2009 a force of 3,000 “New Police” were commissioned. The Mexican army trained the “New Police” recruits who began patrolling the city along side the army units.

Juarez experienced a five-fold increase in drug cartel-related executions between 2007 and 2008, when executions reached a record setting 1606 for the year (see Table 2). In February 2009, the cartels threatened to kill a policeman every 48 hours until the then Chief of Police, Roberto Orduña, resigned. Orduña, a former army major, had held the post less than a year and had been spearheading the efforts to clean up the Juarez Municipal Police. When the cartels made good on the threat, launching a new wave of police executions, the Chief resigned, prompting the federal government to activate extraordinary measures. In March of 2009, control of the Juarez Municipal Police was essentially transferred to the army under a unique agreement in which the army permitted more than 30 retired or active duty army officers to assume command positions. The army began patrolling alongside the police at this juncture. In addition, 10,000 army and 2,000 Federal Police arrived to reinforce policing functions within the city.

Table 2: Juarez Executions 2007-2010 (Source: El Diario de Cd. Juarez)

2007 301

2008 1,606

2009 2,754

2010 3,111

Total Executions 7,772

There were significant problems associated with the strategy of using the army as an interim force while a new police force for Ciudad Juarez was recruited and trained. The most obvious was that the military was not trained for civilian law enforcement work. In addition, there were no mechanisms in place for a smooth interface between the military and the civil judicial process. The military was not efficient at collecting and analyzing evidence, nor was it efficient at preparing such evidence for criminal proceedings in the courts where suspects were formally charged with crimes and trials were undertaken. In addition, complaints of human rights abuses took a precipitous jump, with citizens alleging that they were being picked up by the military and tortured for information. There were also many complaints that the military was entering homes without search warrants. In addition to these substantive problems, there were also logistical problems in terms of housing and feeding that many troops (the city rented out five enormous maquiladora -assembly plant- warehouses for this purpose).

Mexican Federal Police

From the outset of the Mexican federal government’s strategy in Ciudad Juarez and elsewhere, the intent was for the Federal Police to eventually replace the army units that were deployed to fight the DTOs. At the beginning of the Calderón administration, the Policía Federal Preventiva, the precursor to the Policía Federal, only had 6,500 agents. The Policía Federal Preventiva became the Policía Federal with the passage of the Ley de la Policia Federal in the Mexican congress that went into effect on July 2, 2009. The former organization, under the so-called “preventive” framework, was limited in its investigative capacities. The new legislation allowed for the Federal Police to both investigate federal crimes and take a more proactive role in its law enforcement efforts. Over the course of the last four years, the Federal Police has increased to the present force of 35,000 agents.

The Policía Federal Preventiva was created in 1999. It was originally under the Secretaría de Gobernación (Mexico’s Secretary of the Interior) and it drew from the Centro de Investigación y Seguridad Nacional (CISEN, Mexico’s federal intelligence agency), the Policia Federal de Caminos (which was within the Secretaría de Comerico y Tansporte), as well as the 3rd Brigade of the Military Police. It was Mexico’s initial effort at creating a single, unified federal police force.[13]

The Federal Judicial Police (PJF), a separate law enforcement agency that was rife with allegations of corruption, disappeared in 2001-2002 and replaced by the Agencia Federal de Investigación (AFI). The aim of the AFI was to create a more professionalized and modern federal law enforcement agency. There were significant efforts to create a clean force. Unlike the PJF, where commanders were appointed by legislators and influential businessmen and were permitted to hire and fire officers at will, within the AFI officers were recruited as a professional corps that was not as subject to political whims. The training was systematic and many officers were recruited from universities and had college degrees. Much of the AFI leadership also received training in investigative techniques and analysis of evidence from international law enforcement agencies such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Scotland Yard, and the French police. These were the first efforts to create a truly modern federal police agency in Mexico and, while the AFI was not immune to the corruption of some officers, it was head and shoulders above anything the country had known previously.

The current Federal Police, under the auspices of the Secretariat for Public Security (who’s director, Genaro García Luna, was the man who spearheaded much of the modernization efforts within the AFI) has continued to build on the framework first established within the AFI (the AFI is now a small force within the Federal Attorney General’s office). Seven thousand of the 35,000 officers that make up the Federal Police are university graduates, and the force is much better trained in modern law enforcement techniques than anything Mexico has known in the past. The Federal Police runs a national database (Plataforma Mexico) whereby police in every state may check suspects’ fingerprints and criminal backgrounds, for example[14]. Every law enforcement officer is also part of the database, thereby facilitating the ferreting out of errant officers who move to another state in order to continue their criminal activity. The Federal Police has an operational wing as well as an investigative and intelligence wing.[15]

Federal Police in Ciudad Juarez

In Ciudad Juarez, the Federal Police that were initially dispatched at the time that the military units were first deployed primarily had an administrative and intelligence role. They also set up the city’s Emergency Response Center. (Until then, the center was staffed by Municipal Police in the pay of the Juarez Cartel and they routinely shared vital information with the cartel, including who it was that was reporting on their activities. This fact was widely known and made citizens understandably fearful of calling the Emergency Response Center to report crimes).

Despite the presence of Ciudad Juarez’ “New Police,” the levels of violence continued unabated, with executions continuing at a record-setting pace, including the executions of police officers. The month of August 2009, for example, registered 320 executions in the city, thus averaging more than ten per day and making it the bloodiest month since the start of the war between the Sinaloa and the Juarez cartels. For this reason, the federal government decided to again reinforce the presence of Federal Police in the city. In September 2009, the second phase of Operativo Conjunto Chihuahua was launched. The army stopped patrolling the streets of Ciudad Juarez and switched to a supportive role, although they continued to be nominally in charge of policing activity within the city. 1,400 Federal Police agents, 400 of them specializing in intelligence, were added to the law enforcement efforts in the city and again, in January of 2010, the federal government announced that 2,000 more Federal Police would be sent to Ciudad Juarez. At present there are approximately 5,000 Federal Police agents assigned to Ciudad Juarez, including 412 patrol vehicles, 8 armored vehicles, 90 motorcycles, and 4 aircraft (three helicopters and one fixed-wing airplane).[16]

The profile of Federal Police activity in Ciudad Juarez had grown steadily since the launch of Operación Conjunto Chihuahua in the spring of 2009. For example, in July 2010, the Federal Police arrested Jesús Armando Acosta Guerrero, alias “El 35.” Acosta Guerrero was an important operational leader of the Juarez Cartel’s armed wing “La Linea” (he received orders directly from “El Diego,” the second in command within “La Linea”). In retaliation, members of “La Linea” set a trap in which a man whom they’d severely wounded was left in the street next to a Ford Focus loaded with explosives. A call was then placed to the city’s Emergency Response Center (CERI) indicating that there was a wounded man at that location. When the Federal Police arrived, “La Linea” operatives detonated the car bomb, killing one Federal Police officer, an emergency responder, a physician who had attempted to render aide and a bystander. The car bomb attack was the first time such a terrorist strategy had been used in Ciudad Juarez. A second and more powerful car bomb was defused in a similar attempt shortly thereafter. In addition, there have been numerous ambushes of Federal Police agents and convoys in the course of the last year, all new tactics.

There appears to be significant tension and mistrust between the current administration of Ciudad Juarez mayor Hector Murguía and the Federal Police. There have been at least two armed confrontations between the Federal Police and the mayor’s security detail. In one of these, one of the mayor’s bodyguards was killed.

In April 2010 the Federal Police formally assumed security responsibility for Ciudad Juarez, taking over all policing functions from the Mexican army. The international bridges as well as airports and highways remain under the control of the Mexican army, as well as the rural areas around Ciudad Juarez, in particular the area known as the Valle de Juarez, to the southeast of the city, long a stronghold of the Juarez Cartel and now a highly contested area between the cartels because its communities run along the U.S.-Mexico border, making them a strategic transit point for smuggling drugs and people into the United States.

In addition to operations against the DTOs, the Federal Police are placing special emphasis on combating the wave of kidnappings (120 of the newly deployed agents are specialists in hostage negotiation and other kidnapping-related law enforcement work) and extortion, crimes that have become epidemic and are increasingly affecting the population as well as commerce. Tactical analysis and field intelligence have become priorities and there are daily meetings with federal, state, and municipal law enforcement as well as weekly meetings with the army, the federal attorney general’s representative, and the Centro de Investigación y Seguridad Nacional.

The Federal Police created a new approach to covering the city. Out of the historic six police sectors, they divided the city up into nine sectors, breaking these up into 156 quadrants, with 24-hour response teams and air surveillance. This meant a more effective distribution of forces in relation to the city’s demographics. In addition, they have instituted a “secure corridors” program, identifying 39 stretches of streets and thoroughfares that have additional patrols and checkpoints in an effort to reduce the incidence of criminal activity are create safe zones within the city. The Federal Police also continued to man the city’s Emergency Response Center (the CERI has received 1,869,234 calls to date, 81 percent of which are hang-ups or prank calls).[17] The CERI was also upgraded, with up-to-date computerized workstations for each of the city’s sectors where calls were received and locations identified as well as the locations of Federal Police units via GPS technology. A citywide computerized map along one of the CERI’s walls permits the contextualization of activity within each of the city sectors in relation to the others. A new command center has been built to house the Federal Police, which indicates that the Mexican government intends to keep the Federal Police in Ciudad Juarez for the long haul. The command center has 100 workstations, 40 of which are dedicated to working kidnapping and extortion cases (these fall under the federal purview).[18]

Conclusion

The continuing violence in Ciudad Juarez altered the federal government’s original strategy. The “New Police,” inaugurated in the fall of 2009 continued to have problems and their limited effectiveness has required the emergence of an approach that includes a longer-term presence of the Federal Police in the city. This became especially evident once the shift was completed away from the Mexican army as the primary law enforcement tool in Ciudad Juarez.

There have been episodic accusations that some elements of the Federal Police were involved in the extortion of businesses. In August 2010, there was a mutiny within one of the command groups (the “3rd Group” or regiment) after agents accused their commanders of pressing them to participate in extortions and pocketing their per diem payments. Four Federal Police commanders who were part of the “3rd Group” in Ciudad Juarez were relieved of their commands and all have been prosecuted.

There is some evidence to suggest cautious optimism that the federal government’s strategy is having an impact on the violence in Ciudad Juarez. The average number of executions for the first six months of 2011 has dropped to185 per month, or close to 2008 levels (134 per month)[19]. By contrast, in 2009 the average monthly toll in Ciudad Juarez was 229 and it was 259 in 2010. Hopefully, such trends can be sustained, although they still translate into six executions per day on average. Similarly, drawing from their own data (which sometimes differ slightly from El Diario’s numbers) the Federal Police reports a 32-percent drop in executions in the first five months of 2011 as compared to the first five months of 2010.[20]

The long-term goals for Ciudad Juarez are to continue efforts to establish the Juarez Municipal Police as a viable force. In addition, the government plans to continue strengthening of the Federal Police on a national level beyond its current 35,000 agents. Finally, the federal government is intent on developing a single police force within each state which would be modeled after the Federal Police. Such a force would be better trained and equipped than are current state police forces and they would work in greater coordination with the Federal Police. Finally, the federal government continues its efforts to improve the Mexican judicial system, presently a weak link in the efforts to control the levels of criminal activity in the country.

[1] Interview with Eduardo Medina-Mora, Mexico’s ambassador to Great Britain and Federal Attorney General until September 2009. London, United Kingdom, September 15, 2010.

[2] Interview with Guillermo Valdés, Director of Mexico’s CISEN – Centro de Investigación y Seguridad Nacional. Mexico City, November 14, 2010.

[3] At the time an additional number of agents were drawn from the CISEN, the army, and other existent law enforcement agencies, but these additional agents remained assigned to their home agencies (Personal Communication, Manuel Balcazar Villareal, Presidencia, Mexico City).

[4] Source: Alejandro Poiré interview at the University of Texas at Austin, April 2011.

[5] Data for number of executions in Ciudad Juarez are from El Diario de Cuidad Juarez.

[6] Personal communication, anonymous.

[7] Hector Murguía was re-elected mayor of Ciudad Juarez in the July 2010 municipal elections and assumed office in October 2010.

[8] Source: El Diario de Ciudad Juarez

[9] Personal communication, José Reyes Ferriz, mayor of Juarez October 2007 – October 2010.

[10] Ibid.

[11] “El Sicario, Room 164,” documentary film directed by Gianfranco Rosi (2011).

[12] February 2010 interview with Facundo Rosas, head of the Federal Police.

[13] Personal communication, President’s Office, Mexico City July21, 2011.

[14] Interview with Genaro García Luna, head of Mexico’s Secretariat for Public Security, Mexico City, November 20, 2010.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Source: Policia Federal en Ciudad Juarez Junio 2011 (Secretaría de Seguridad Pública, Mexico, D.F.) (p.24)

[17] Source: Policia Federal en Ciudad Juarez Junio 2011 (p.24)

[18] Policia Federal en Ciudad Juarez Junio 2011 (p.74)

[19] Source: El Diario de Ciudad Juarez

[20] Source: Policia Federal en Ciudad Juarez Junio 2011 (p.25)