“If you take care of the land, the land takes care of you,” said Wenceslaus “June” Provost Jr., a fourth-generation sugarcane farmer from Louisiana. “For me, farming is everything. It’s my life. It was never a job.”

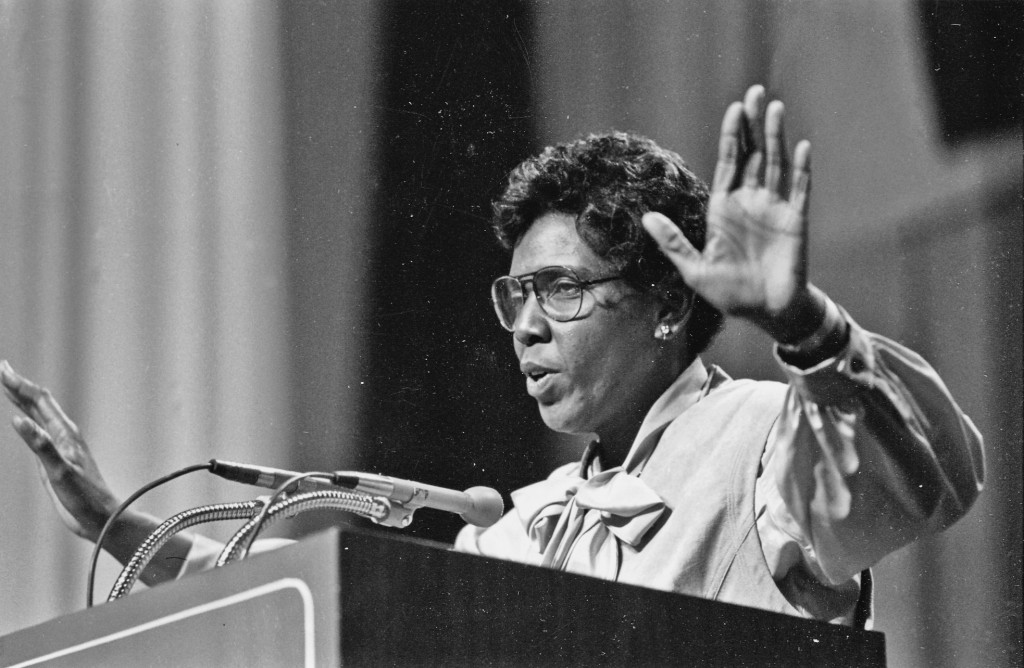

Provost spoke to a packed room on Feb. 19 with his wife, Angie, as part of the LBJ School’s 23rd Annual Barbara Jordan National Forum. The Provosts, who were featured by the New York Times’ acclaimed “1619” podcast, spoke about the legacy of black land ownership in America and the racial discrimination and harrassment they experienced as black farmers in the South.

Provost grew up working his family’s 5,000 acre farm with his father and brothers, going out in the fields with his father when he was as young as five. In 2008, the Louisiana Farm Bureau named Provost “Farmer of the Year” for Iberia parish. After his father retired and Provost took over the farm, things started to unravel.

The Problem

It started at the bank. Loans typically provided in February were not approved until June, and the loan amounts Provost received were for far less than he needed. Not able to hire enough workers to start planting until the money came in, Provost was stuck planting sugarcane too late into the fall. This led to poorer harvests and left his farm in disrepair.

After years of underfunded loans, impacting his ability to buy and repair equipment and hire workers, Provost lost his family’s farm in 2014, and four years later, June and Angie Provost foreclosed on their home.

According to reporting by “1619,” June realized the bank’s actions may have been intentionally discriminatory after a local U.S. Department of Agriculture officer tipped them off and allowed them to review the loan files. Provost alleges that the files show First Guaranty Bank changed his loan applications without his knowledge, including photocopying his signature and reducing the requested loan amounts. Due to an ongoing lawsuit against First Guaranty Bank, the Provosts were unable to discuss the allegations in detail at the event.

The Provosts said what happened to them is not unique, but rather a pattern of racial discrimination and evidence of a “land grab happening across the South” to black farmers, representing a huge loss of generational wealth. Provost said when he was growing up, there were around 60 black-owned sugarcane farms in the area, making up about 60,000 acres of land. Now, there are only four black families operating in the area. According to Provost, nationwide, black Americans make up less than 1 percent of U.S. landowners, and they’re losing up to 30,000 acres of land a year.

“It starts with all of these tactics of plantation economics that have stemmed from enslavement to Jim Crow to now,” said Angie Provost. “The system is not broken, it’s doing what it was exactly designed to do…the discrimination is so systematic and complex.”

Part of the problem is that getting restitution for civil rights is difficult, especially in the South, Angie Provost explained. It is difficult to find civil rights lawyers or sympathetic politicians to serve as advocates, and the vast amounts of money funneled into the sugarcane industry create a monopolistic culture that is difficult to navigate. Sugarcane is the number one lobby crop at the federal level, making it the “cash king” of the South, the Provosts said.

The Provosts went public with their story to raise awareness for what is happening to black farmers across the South, and they say their new cause is promoting and protecting black land ownership. They see the solutions as two-fold.

The Solution

The U.S. must increase the statute of limitations for civil rights laws, so other black families who lost their land can speak up and get restitution. Angie Provost said many families were forced off of their farms decades ago, and have no recourse with the current legal system.

“People who are suffering…they’ve been out of farming since the early 2000s. But what if they could go back? They hear our story and they go ‘Oh this happened to us!’ But now, they’re blocked from speaking up against it because of the statute of limitations,” said Angie Provost. “So I think a big part of that would be to get our civil rights laws—treat them more like criminal laws, because they’re crimes against humanity.”

Secondly, the Provosts believe it is critical to engage and educate the next generation of black children so they see farming as a viable career path. The Provosts frequently visit schools, and said they eventually want to build a heritage center, where families could learn about the history and science of agriculture and black farmers. Ultimately, they want to teach young people that building wealth stems from land ownership, and the ideas of farming and slavery must be decoupled.

“We can all talk about the imagery of the American Gothic painting and what that means to White people, right? But every time I look at a book about farming and black farmers, they’re showing me a picture from 1830 of someone picking cotton,” said Angie Provost. “That’s not to disparage them, because we stand on their shoulders, but it also means that we have a right to our legacy, we have a right to what we built here, and we have a right to take that story and that narrative back.”

Learn more about the LBJ School’s 23rd Annual Barbara Jordan National Forum here: https://lbj.utexas.edu/23rd-annual-barbara-jordan-national-forum

Or learn more about the Provosts and their work at: https://www.facebook.com/cultivateequity/