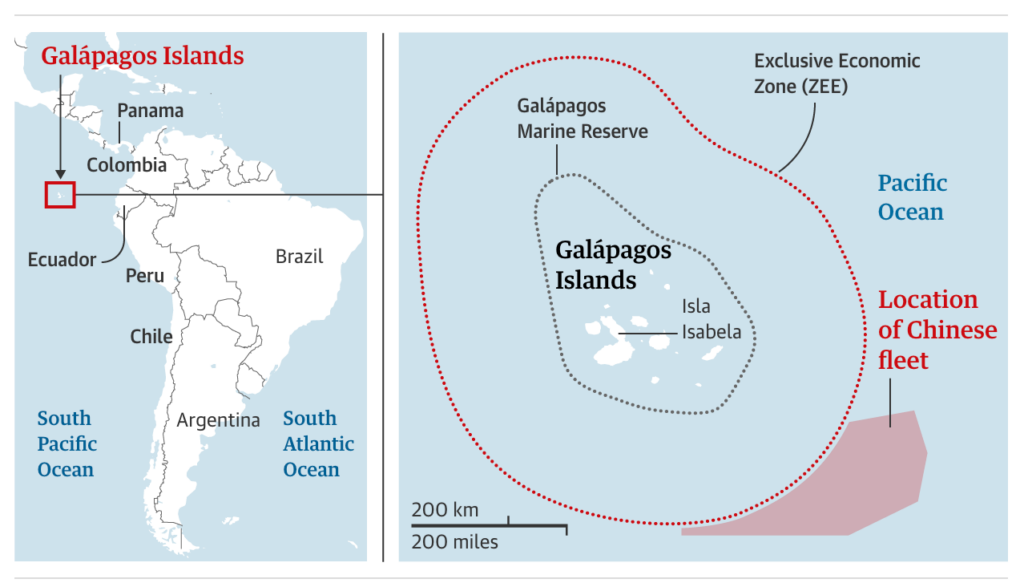

“Exactly what happens in the Galápagos [Islands] happens in locations around the world and it’s terrifying.” These were the words of Mercedes Rosello, director of House of Ocean, a not-for-profit legal consultancy that monitors illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUU fishing), in response to a massive buildup of Chinese fishing vessels off the coast of the Galapagos islands in the fall of 2020. Sadly, this is nothing new. This specific occurrence of long-distance fishing looked to have occurred just outside of Ecuador’s Exclusive Economic Zone, what has become a classic strategy of nations looking to extract ocean resources far from their borders while still maintaining a veil of legality. These vessels often use tactics such as shutting off their transmission responders in order to avoid detection. China’s vast fishing vessel fleet, now the world’s largest, has been found off the coasts of West Africa to Latin America, plundering ecosystems and disrupting coastal communities around the world. In West Africa, for example, a 2018 report by the Environmental Justice Foundation found that 90% of Ghanaian-flagged vessels had Chinese involvement. As detrimental as these vessels can be, the problem persists far beyond the global movement of Chinese fishing vessels, and global action is needed to correct the drivers, access and punishments for such activity. Apart from the environmental concerns stemming from the global overfishing threat, including declining biodiversity and damage to sea beds, overfishing causes damage to developing nations who rely on seafood as a major source of employment and subsistence and lack the monitoring capabilities to adequately protect their seas.

Out of Sight, Out of Mind

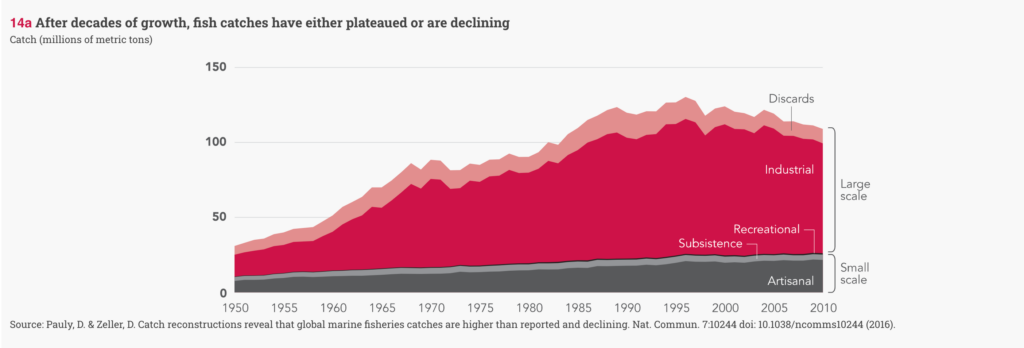

Overfishing persists largely as a governance challenge. Oceans remain a common pool resource, and therefore present a significant challenge of regulation. Attempts have been made to provide excludability to oceans, but much of our oceans remain like the wild west: lawless and unmanned. Regional Fishery Management Organizations (RFMOs) have primarily been charged with managing and conserving fish stocks in a particular region, but historically, they have been unsuccessful at preventing overfishing and maintaining healthy fish stocks. RFMOs were not made for and are not able to adapt to today’s plundering of the oceans as a result of their fundamental design structure. Ocean resources are clearly not unlimited, as they perhaps were once thought to be. Fisheries management must adapt as well. Countries such as China have virtually transformed the fishing game with massive fleet sizes that seem to answer to no one. Rethinking ocean governance that takes into account modern technological advances must be implemented to stop as well as reverse the negative impacts of overfishing.

A global fisheries management organization could be an answer to this issue. Borders do not exist in the open ocean, so how should we expect for regional management units to effectively manage the borderless existence of sea life? A global fisheries management organization could effectively convene scientists to ensure that catch limits are made with sound data, countries can coordinate on fishing issues of mutual concern, and create best practices for issues like port-based controls to combat overfishing, among other governance concerns.

Operating with Impunity

The high seas remain one of few modern wildernesses of our day. While this may sound a touch romantic, this vast swath of our planet is one that remains largely unpoliced with no clear international authority; a perfect place for criminals to operate with impunity. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), IUU fishing activities are responsible for the loss of 11–26 million tons of fish each year, which is estimated to have an economic value of $10–23 billion. Much of the illicit fishing activity coincides with forced labor and human trafficking. For example, take the case of Thailand, where such abuse is common. Men or boys are offered a job in construction or some other lucrative industry by a human trafficker. The trafficker tells the worker that the debt incurred during passage will be settled at a later time. When the worker arrives at the port and realizes the job is on a fishing boat, the debt the worker accrued is used to sell him to the fishing boat captain, at times keeping these boys and men captive at sea for several years at a time in inhumane conditions. Tackling the issue of illegal fishing as a contributor to overfishing and human rights abuses is essential. Monitoring and enforcement of such IUU fishing should be done in collaboration with organizations like the International Labor Organization along with the International Maritime Organziation.

Grades Matter for a Sustainable Fishing Market

Just as much as the decisions of commercial fisheries matter, so do that of consumers. Providing easily digestible information on the sustainability of seafood to consumers is of the utmost importance to transform demand for sustainably caught sea food. The Marine Stewardship Council has in fact already created an MSC blue fish label, which is applied to wild fish or seafood producers from fisheries that have been certified to the MSC Standard. The global volume of tuna caught to the MSC’s globally recognized standard for sustainable fishing more than doubled from 700,000 tons in 2014 to 1.4 million tons in September 2019. Further work on giving consumers the right information to make smart choices that enhance the market for sustainable fish could also go a long way in motivating fisheries to adopt more sustainable practices. Putting pressure on major international grocers to only buy MSC blue label certified seafood, but also approving the grocer as an MSC certified grocer could make for a strong incentive for grocers to “go green” with their buying choices, as well as arm consumers with information to make good use of their purchasing power.

Addressing overfishing from a governance, demand, and human rights perspective is needed to shed light on a topic that has not gotten its fair share of attention. At its surface, the term overfishing doesn’t often strike a tone of importance in the minds of your average person, but it should and must. As a consumer, you can use your purchasing power to shop sustainably at your local grocery store, or urge your store to stock such products. At the global level, governance structures need a complete overhaul along with revolutionary information and data transparency to drive informed decision making, and finally, a fundamental transformation of the issue is needed to take into account the grave human rights repercussions resulting from overfishing which persists around the world.

Caroline Corbett