Spillage and Under-reporting

Everyone remembers how crazy it was to hear about the BP oil spill and the sheer extent of damage caused to marine life and habitats. Pictures and videos of volunteers washing the sludge off of seabirds and marine mammals could be seen everywhere. It was close to home, and it really began to bring public attention in the US to the devastation that these accidents could cause. A nation where hundreds of miles are occupied by refineries, pipelines, and rigs. But why did it take this long for people to notice, or even care? I mean, even without oil spills, according to the US Department of Energy, the amount of petroleum that ends up in US waters averages to about 1.3 million gallons per year, with the potential to double in the case of an oil spill. That is, if all the dumps were reported.

Back in 2004, Hurricane Ivan knocked loose a lip of sediment on the continental shelf, which resulted in an underwater avalanche that knocked down an oil platform owned by Tyler Energy, severing its connection with more than a dozen wellheads in the Gulf of Mexico. Instead of going public with the information about the massive oil spill, however, the Louisiana-based oil company decided to secretly work on recapping the well, unsuccessfully, for six years. Due to lack of immediate impact to local communities and no loss of human life, Tyler Energy and the government continued to keep it under the table until in 2010, when researchers were doing a flyover to measure the extent of the damage of the 4 million gallon BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill. It wasn’t until 2019 that the United States Coast Guard, in coordination with a private contractor, were able to cap the well after 15 years of spillage at 300-700 gallons of oil a day.

Under-reporting has been a prevalent issue in the Gulf, as there are fines for not reporting leaks, but none for under-reporting. Oil companies are incentivized to keep the extent of leaks and spills secret, reporting numbers that are sure not to garner too much unwanted attention from the public or environmental groups. COVID has only amplified this issue, after the legislation passed by the Trump administration early last year. Last year during the beginnings of the pandemic, the Trump administration declared that it was no longer mandatory to comply with monitoring and reporting of pollution, so the reporting for oil spills and other environmental pollution for the year of 2020 is scattered, and the actual extent of environmental damages is unknown.

More than just Oil Spills

Offshore drilling holds more risk than just oil spills. As explained by the Surfrider Foundation, offshore drilling comes with a myriad of environmental impacts, causing far more damage than oil spills and are much less visible.

Oil Exploration through seismic surveys, or commonly referred to as ‘air gun blasting’ are conducted to find the location and parameters of potential oil reserves. These ‘blasts’ of high decibel impulses can harm or kill marine life, deafen marine mammals, disrupt migratory patterns, and have also been implicated in whale beaching and stranding. Drilling muds, the combination of polluted water and drilling chemicals released from drilling and processing oil, contain high concentrations of metals and are toxic to marine life, but are dumped back into the ocean if measured to be under a certain level of toxicity. Air quality is also degraded as a result of offshore drilling, as volatile organic compounds are released into the air from oil platforms, leading to water quality deterioration, smog, and more.

Onshore, environmental impacts are felt too, as extensive infrastructure is needed to support the refining and transport of oil on land. Pipelines, refineries, and production facilities all need to be operated to support offshore drilling facilities. The space and resources needed to operate these facilities takes away from the environmental resources of local wildlife and can from local tourism associated with the coast, as shorefront property is utilized to facilitate the refining and transportation of oil. The on-land transportation of oil also has its own risks, as seen with the Keystone Pipeline, which burst twice in two years and on its second spill leaked over 400,000 gallons of crude oil into a North Dakota wetlands in 2019.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/f3/a6/f3a6fe69-8562-490e-82b8-1f47d7440842/ap_17322182296131.jpg)

What’s in the Future for Offshore Drilling?

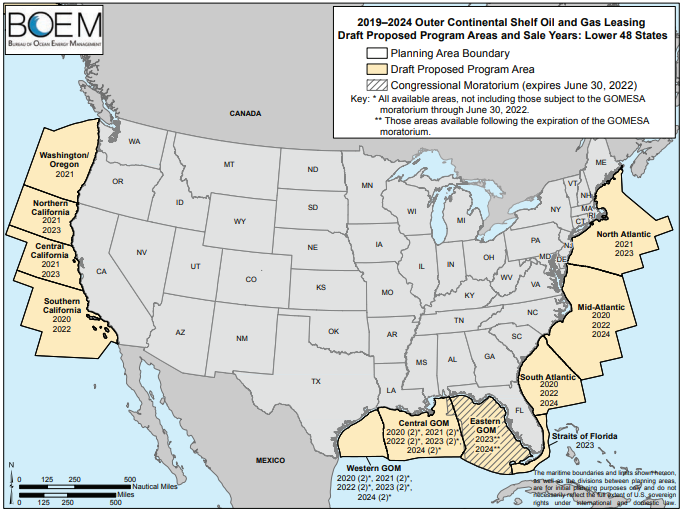

Despite the negative tone of this article, the future is looking cautiously optimistic. Last week, New Jersey Rep. Frank Pallone announced his intention to move forward with filing for a bill that would ban offshore drilling in the Atlantic permanently. This legislation comes as President Joe Biden pushes the American Jobs Plan, which aims to rebuild America’s energy infrastructure, supporting the production of clean energy while investing in the cleanup of old and abandoned oil and gas wells and mines. These proposals come as a welcome change of pace for environmentalists and ocean conservationists, after the Trump administration’s proposal to open oil and gas deposits off the coastlines of the Atlantic, Pacific and Arctic oceans in 2018.

Farther south of America’s borders, however, plays out a different story. BPC, Bahamas Petroleum Company, is focusing on developing oil reserves off the coasts of Trinidad and Tobago and Suriname, moving in alongside the oil giants ExxonMobil and Total after the latter discovered large reserves off the coast of Suriname earlier this year. This decision only comes after 48 days of exploratory drilling in the Bahamas, when the company determined that the reserves were not commercially viable and that the site would be sealed and abandoned. The Our Islands, Our Future campaign has been vehemently opposed to these operations, and have taken the government and BPC to court for the non-transparent granting of permits late last year. Damages caused by the initial drilling are yet to be determined if they fall under insurance provided by the company, and leaders of the campaign are fighting to prevent any more action taken by BPC in the Bahamas. You can sign their petition here to help fight for the permanent ban of all fossil fuel exploration in the Bahamas.

Though under-reporting and the adverse environmental issues of offshore drilling remain an issue, current legislation to fight these industries seems promising, and the quicker that America can become less reliant on fossil fuels, the faster these operations will become less prevalent.