Ocean Acidification Needs Attention

The earth’s oceans are known to be in danger. Plastic pollution, oil spills, and diminishing fish populations are just some of the popular threats people will recognize. One threat, however, poses potentially greater and longer-term damage but is relatively unknown and under-researched — ocean acidification. Acidification is an enormous threat to marine life, ocean and global environmental stability, and communities across the world. The biggest obstacle, though, is we do not know nearly enough to make effective policies.

The oceans play a significant role in the stability of our planet’s climate and systems. Specific to the discussion, the oceans function critically in the carbon cycle by sequestering 50 times more carbon than the atmosphere. Through a variety of paths, such as wind and waves, surface waters absorb carbon dioxide (CO2), which dissolves into the water as carbonic acid and breaks down into bicarbonate and hydrogen ions. Since the start of the industrial revolution, humans have dumped almost 40 gigatons of CO2 into the atmosphere, which has made its way into the oceans. At the current level of oceanic CO2, the pH of surface waters has lowered (grown more acidic) by .1 pH units, which seems like a small number, but represents a 30% increase in acidity since pre-industrial levels.

Ocean acidification poses a significant threat to marine life and communities. All marine life rely on stable ocean chemistry for their security. Changes in ocean acidity have shown to affect the sensory skills, formation, and life span of several species of flora and fauna. Mollusks and other calcifying animals, like crabs and coral, build their shells and skeletons by using the calcium and carbonate from seawater. The process of acidification leaves fewer carbonate ions for these animals to use. Worse still, if the seawater becomes too acidic, it can dissolve the shell or bone. For example, one study placed pteropod shells in seawater with the pH level predicted for the year 2100, and the shells dissolved within 45 days.

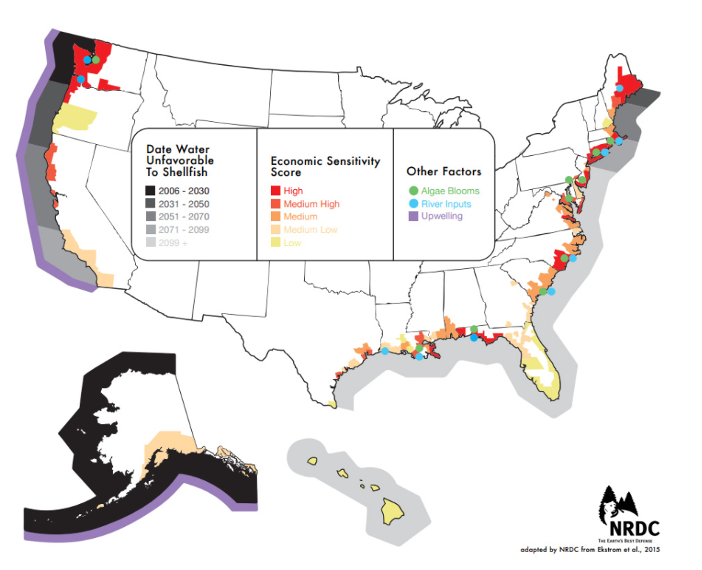

Our oceans directly support the economies and communities around the world. For 8% of the world population, the oceans and marine life provide income. And, for the rest of the world, the oceans provide a staple of their diet and form a large part of their cultural identity. Ocean acidification threatens these communities by ruining the future of these economies and cultures. In the United States, the Pacific Northwest population of North Pacific crab, which is the highest revenue fishery in the region, is decreasing significantly due to rising temperatures and acidity. Toxic algae blooms are on the rise and force the closure of nearby fisheries because of the risk to human life. The American economy could experience a $230 million USD loss in the shellfish industry and a $150 billion USD loss in benefits from tourism and recreation.

Acidification is occurring at a faster rate today than any other point in the last 66 million years and maybe even the last 300 million years. By the end of this century, the oceans could be twice as acidic as they were last century. While these tipping points may seem far, far away, the chemistry of the world’s oceans cannot change in a year or even several. For the oceans to return to an optimal pH level, the world would have to stop all CO2 emissions immediately and wait hundreds of years for natural cycles and processes to sequester the carbon. This is why action on ocean acidification is so urgent. The consequences of inaction will last for generations!

Unfortunately, because ocean acidification is relatively new in the science community, there is a lot of uncertainty in the problem itself and only a few theories on solutions. Therefore, there are primarily three ways to mitigate ocean acidification and prevent the planet from reaching that threshold: reducing carbon emission levels; invest in carbon sequestration technology, such as seaweed beds; and, promote and fund programs that researches and monitor acidification and its impacts.

Carbon Emissions Reduction

With the current level of technology and understanding of the issue, the primary tool against acidification and our greatest hope to prevent the worst outcome is the reduction of global carbon emissions. Continuing the current rate of emissions would only ensure water acidity reaches catastrophic levels. This would require a global, collective effort to shift to renewable, carbon-neutral energy sources. A step further would include the prevention of large forest fires and other forms of air pollution.

Emissions reduction seems like and is a large goal. But, similar to Climate Change, until we have technology with the ability to quickly and efficiently remove carbon from water, emissions reduction is the best bet. On a global scale, this will work efficiently with technology sharing, transparency, and clear goals. Although a complete halt in emissions is nearly as easy as a fantasy, any reduction will affect the severity of the problem and how far we will need to adapt.

Carbon Sequestration

Although I just mentioned the lack of sequestration technology, there is an organic and potentially viable method to capture some carbon and affect local acidity levels — seaweed. If you are familiar with forestry and its role in Climate Change, or wetlands and water quality, then you will understand how seaweed can affect ocean acidification. Particular plants have an awesome ability to filter water of pollutants, excess nutrients, and more. Seaweed is proven to be successful in capturing carbon and nitrogen from its surrounding water. For example, kelp, a type of brown seaweed, can take in five times more carbon than most land-based plants.

I consider seaweed as separate from the mentioned missing technology because they are really only an option for addressing local acidity levels. In California, it is being used along the San Fransisco coast for oyster farms and other fisheries as a way to ensure optimal pH levels. The government is also funding marine plant life near wastewater treatment plants to capture any pollutants. Similar seaweed forests can be planted around the globe. They are appealing to wildlife conservationists and ecologists because they form the habitats for many sea creatures and are threatened by warming oceans, too.

Form a Global Community

The biggest obstacle to finding solutions and acting on them is the uncertainty within the science and policy communities on the issue itself. As mentioned, ocean acidification is a newer problem and still being researched on larger scales. Institutions like NOAA, OA-ICC (Ocean Acidification International Coordination Centre), UNESCO, and more, are releasing programs that aim towards increasing the collective body of research on this important issue. A greater understanding of this problem will be instrumental in finding better solutions and better ways to adapt.

A long-term global community is the first step. Once we have better research and better information, we will need institutions and actors that build capacity among global communities to make changes and advocate across governments for policy initiatives. These institutions will need to reach local communities just as well as they reach state governments. On the local level, scientists face huge gaps in information and capacity. A primary function of this community will need to include reaching local stakeholders and partners to assess needs and support the implementation of solutions. A global community built on the foundations of transparency, communication, and science will be best structured to tackle an issue like acidification, an issue that requires a collective effort.

On an individual level, the most important thing you can do to help fight ocean acidification is to spread the word and reduce your own carbon footprint. The snowball of change will not start rolling and growing until more people know the stakes of inaction. Advocating for clean energy and better policies will point the public opinion in the right direction. The future of communities, cultures, and marine ecosystems is threatened. We need to push the ability of science and policymaking in order to protect the future of our planet and its life.

Written by Weston Weber