The Amazon Rainforest is an invaluable resource not only to Brazil, but to the world as one of the planet’s major carbon sinks. However, in recent years, rapid deforestation poses a major threat to the Amazon and its climate-stabilizing abilities.

Can carbon markets help to address the issue of deforestation in the Amazon?

The Amazon

- Resources

- “Lungs of the Earth:” the Amazon is produces 20% of oxygen generated from land-based photosynthesis (Source)

- It is home to 400-500 indigenous tribes. (Source)

- The Amazon generates an estimated US$317 billion at least annually, (Source)

- and contributes to approximately 10% of Brazils GDP. (Source)

- Its wildlife has immense research and medical value. (Source)

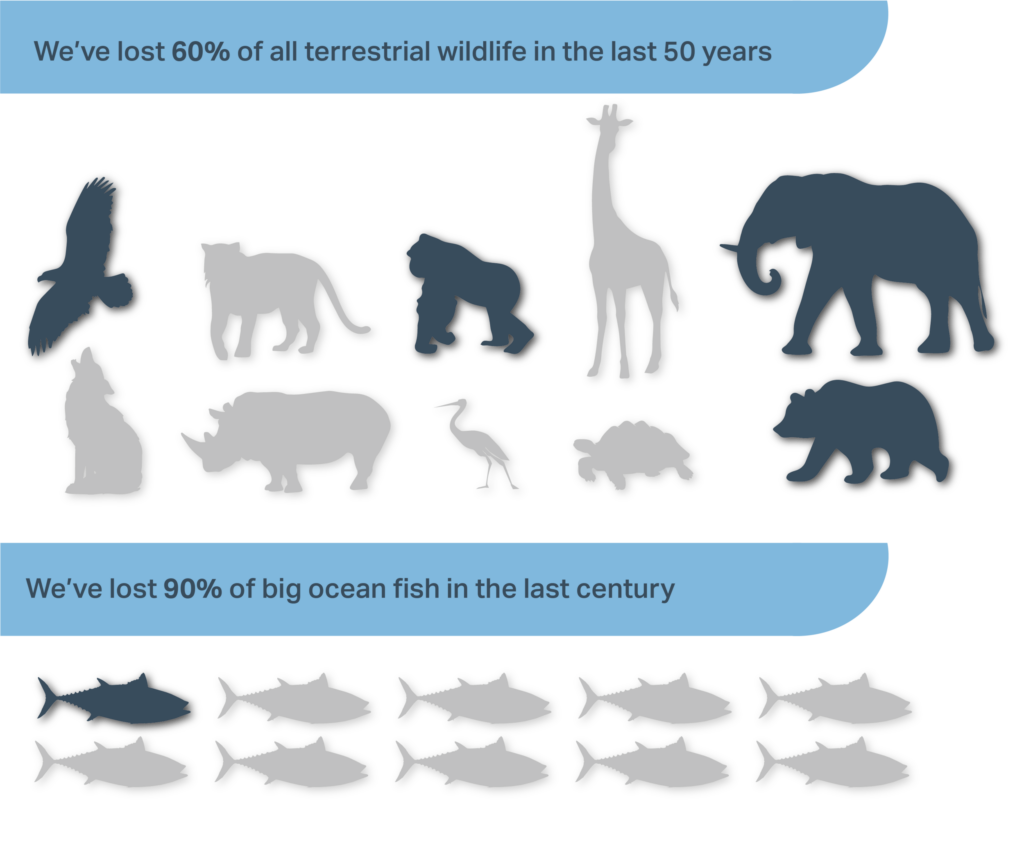

- Biodiversity

- The Amazon is home to:

- 40,000 plant species,

- 3,000 fish species,

- 1,300 bird species,

- 430 mammal species

- 2.5 million insect species

- Many endangered of which are endangered

- (Source)

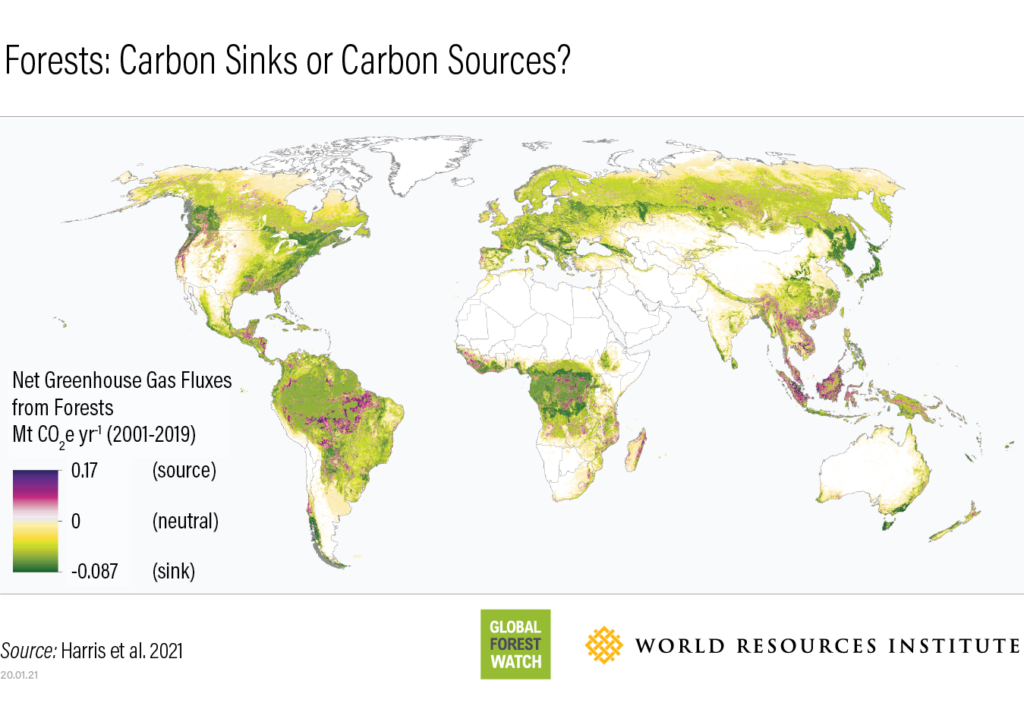

- Climate

- Carbon Sink: The Amazon currently takes in and stores more than 150 billion [metric] tons of carbon. (Source)

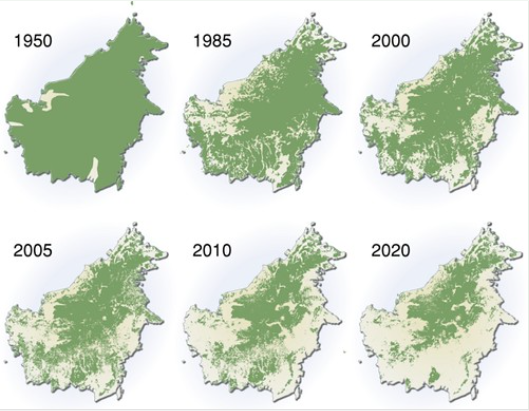

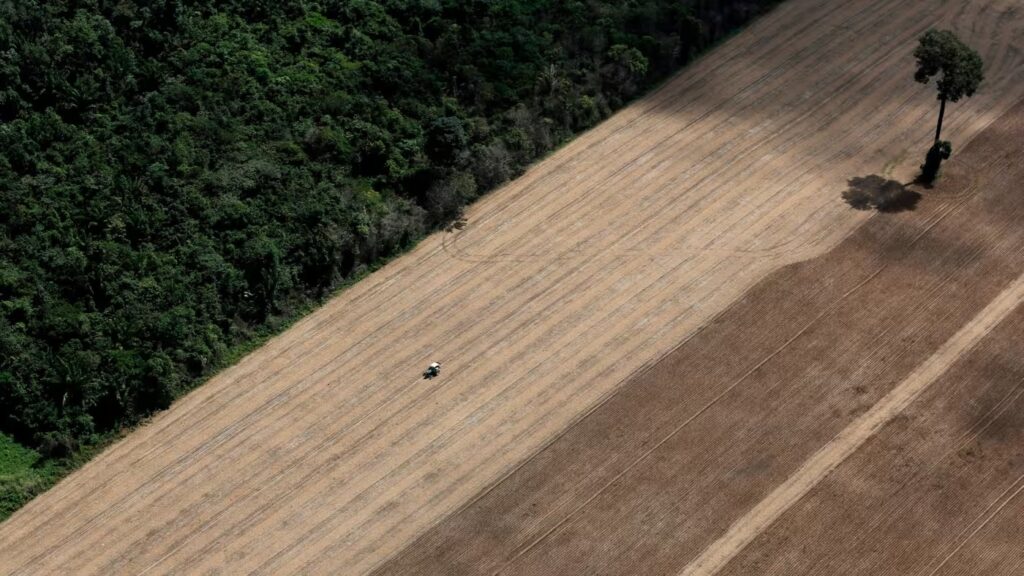

Deforestation

“Over the past 40 years, 20% of the Amazon Rainforest has already been cut down”

One Tree Planted

- The leading driver of deforestation both globally and in Brazil is cattle ranching. (Source)

- Almost all deforestation in the Amazon is unlawful, resulting from illegal ranching, mining, and logging. (Source)

- Deforestation increased under the administration of former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, which cut resources for environmental protection. (Source)

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva & Brazilian government restore pledge to “halt deforestation completely by 2028.”

Financial Times

Deforestation also generates emissions…

- Brazil is the 5th largest emitter of CO2 in the world

- Deforestation and agriculture account for 70% of Brazil’s emissions.

- 50% of emissions come from deforestation alone.

- (Source)

This means to meet Brazil’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of a 37% reduction of CO2 emissions by 2025, and a 43% reduction by 2030, Brazil must focus on reducing deforestation.

“Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has said he will do ‘whatever it takes to have zero deforestation.’”

Financial Times

Carbon Markets

To help address this issue, Brazil could turn to carbon markets.

How Do Carbon Markets Work?

- Creating Credits: Projects that reduce CO2 would earn tradable permits/credits/offsets.

- Forests & Credits: Projects that focus on reforestation, forest protection, etc. could sell credits since they reduce carbon by maintaining a carbon sink and reducing carbon released from deforestation.

- Creating Demand for Projects: Polluters who cannot meet emissions goals must purchase offsets, generating demand for these carbon credits. By allowing beneficial forest projects to generate credits, demand for projects that focus on forest protection and/or rehabilitation is also generated.

Recently, lawmakers in Brazil have introduced legislation that would establish a national cap-and-trade system, in which the government would set a “cap,” or “upper limit,” to the amount of CO2 emissions an entity could produce. If entities cannot reduce their emissions to this amount, they will need to purchase carbon permits/credits/offsets. (Source)

Brazil hopes that by tapping into both compliance carbon markets, and voluntary carbon markets (VCM), an estimated $120bn could be brought to Brazil’s economy. (Source)

Potential Problems

- Greenwashing: Skepticism has emerged around carbon credits, as recent reporting has shown that projects often do not generate the benefits they claim to. Studies have shown that only between 10% to 30% of credits traded on the Voluntary Carbon Market are delivering their claimed impact. (Source)

- Agriculture Exemptions: Concerns have also emerged around Brazil’s proposed cap-and-trade system due to exemptions made for agriculture; one of the leading drivers of deforestation and one of the largest sources of CO2 emissions in Brazil. (Source)

Here is how various actors can address this issue:

States: Brazilian Government

- Establish Cap-and-Trade system

- Establishing a compliance market will force polluters who cannot meet emissions targets to buy credits, driving demand for positive forest projects that generate credits.

- Create and enforce standards and regulations around Forest projects

- The Brazilian government would tightly regulate which projects take place and where, and should continue to work to enforce environmental protections.

- Work with IOs & Private Actors to ensure quality of credits

- Governments can help identify areas of priority for projects, and should work with private actors and IOs in establishing proper verification measures.

- Continue setting national goals related to Forest and Climate

- Setting goals like halting deforestation and NDCs drive national policies that promote forest protection.

- Explore other non-market options; such as Indigenous land tenure

- Indigenous land tenure has shown to be effective in increasing forest cover. The Brazilian government should work to promote policies that award Indigenous communities land tenure in the Amazon.

Private Actors

- Demand side offset buyers should purchase offsets strictly from projects using advanced baseline calculation methodologies such as…

- “Dynamic baseline,” which uses new technologies such as remote sensing, high-resolution satellite imagery, machine learning, LiDAR, artificial intelligence and real-time data transmission to improve project monitoring

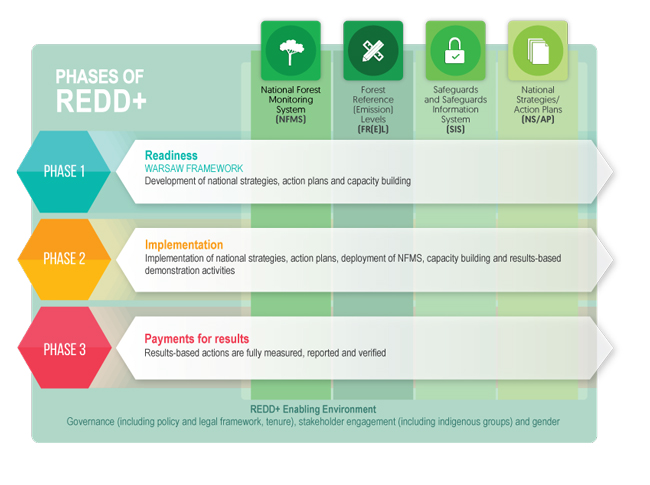

- Jurisdiction REDD+, which represents a new generation of forestry projects that uses jurisdictional forestry data to issue credits in ways that help prevent leakage

International Organizations: UNEP

- Set a common standard for evaluating and monitoring carbon credits.

- Work with communities and states to discover new opportunities to prevent deforestation.

- Facilitate transfers of carbon credits between states and private actors.

- Become a global, central authority on carbon credits to ensure long run validity.

Conclusion

The market for carbon credits in its current state is not going to achieve the goals we would like to see regarding deforestation unless it undergoes significant changes. However, steps can be taken to address this issue. States can continue setting national goals on deforestation, establish a cap and trade system, enforce standards related to deforestation, and work with IOs and local communities to identify priority conservation/reforestation areas. Additionally, Brazil can explore non-market options, such as Indigenous land tenure which has shown to effectively increase forest cover. International Organizations can become a central authority on carbon credits by setting a common standard, facilitating trades/transfers of credits, and working with states and locals to ensure credits are only being created based on at-risk areas. Private actors can come together to set industry standards, such as purchasing offsets strictly from projects using advanced baseline calculation methodologies. Alternatively, private actors can contribute to an international climate finance fund, such as the Green Climate Fund, to help developing tropical nations reach their nationally determined contributions.

Learn More:

Recent news:

- The Financial Times: Brazil to launch regulated carbon market

- The New York Times: Can Forests Be More Profitable Than Beef?

Posted on May 6, 2024 by: Brandon Mulder, Cody Steverson & Kate McCarroll