Over-tourism is both part of the problem and the solution.

Coral reef bleaching episodes have increased in frequency and intensity over the last few decades, and projections indicate that live coral reefs could decline by 70-90% by 2050 without drastic action to limit global warming to 1.5°C. Coral reefs are among the most biodiverse and economically significant ecosystems on earth, and their preservation is essential. When corals become stressed due to higher ocean temperatures, pollution, or some other stressor, they expel symbiotic zooxanthellae, which removes their color and increases their susceptibility to disease and death.

While climate change and overfishing are significant contributors to the coral reef bleaching crisis, attempts to reach an international consensus regarding such topics have failed. However, the tourism industry, also to blame but often overlooked, has the unique opportunity to influence reef management and conservation practices from the bottom up.

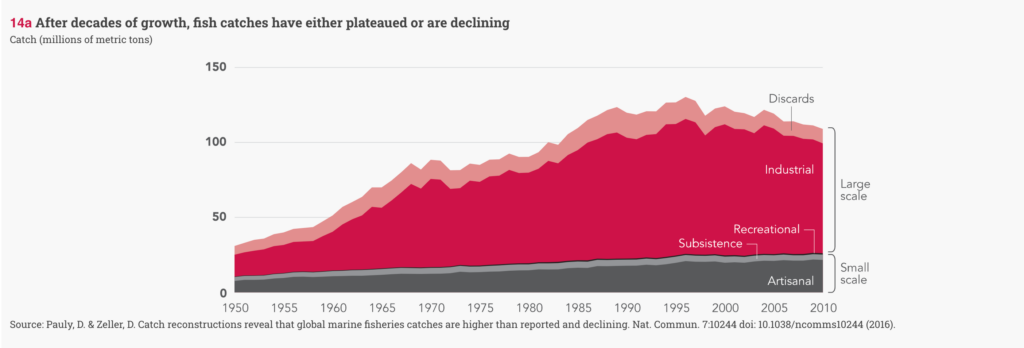

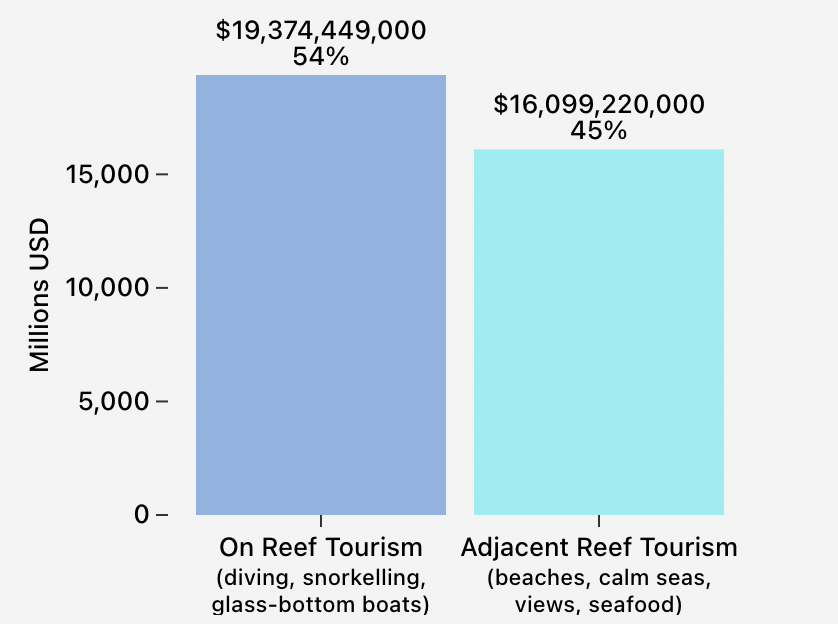

With a staggering 70 million people flocking to coral reefs each year, coastal tourism, accounting for 85% of global tourism, has placed immense pressure on these fragile ecosystems. The demand for reef tourism is reflected in the economic footprint of on-reef and adjacent-reef tourism, amounting to about $19 billion and $16 billion each year, as depicted in the graph above. Unfortunately, the repercussions of over-tourism are severe, exacerbating reef vulnerability to bleaching and other environmental stressors. Moreover, it poses a long-term threat to the health of these ecosystems and the communities that depend on them, underscoring the urgent need for sustainable tourism practices.

Over-tourism harms coral reefs.

One major concern is direct physical damage. Even well-meaning snorkelers and divers can accidentally bump into coral with their fins or struggle with buoyancy control, causing breakage. Additionally, recreational boats can leave a devastating footprint. Their anchors scrape and break fragile coral structures, leaving lasting scars on the reef.

Beyond physical harm, chemical pollution poses a serious threat. Sunscreens containing chemicals like oxybenzone and octinoxate wash into the ocean as tourists swim. These chemicals disrupt coral growth and reproduction, weakening the very ecosystems we come to admire. Reef-safe sunscreens help to combat the problem because they are made with less harmful ingredients, but very few know about this problem and even fewer are incentivized by government interventions to make the switch. Improper waste disposal and inadequate sewage treatment further compound the problem. This influx of pollutants smothers corals and disrupts the delicate balance of the reef’s ecosystem.

The tourism boom also drives unregulated coastal development to accommodate hotels, restaurants, and infrastructure. This development, in turn, leads to increased sedimentation. Sediment runoff chokes coral, blocking sunlight penetration, a vital source of energy for these organisms. Deforestation to clear land for development further exacerbates erosion and sedimentation problems.

Well-managed ecotourism could actually benefit coral reefs.

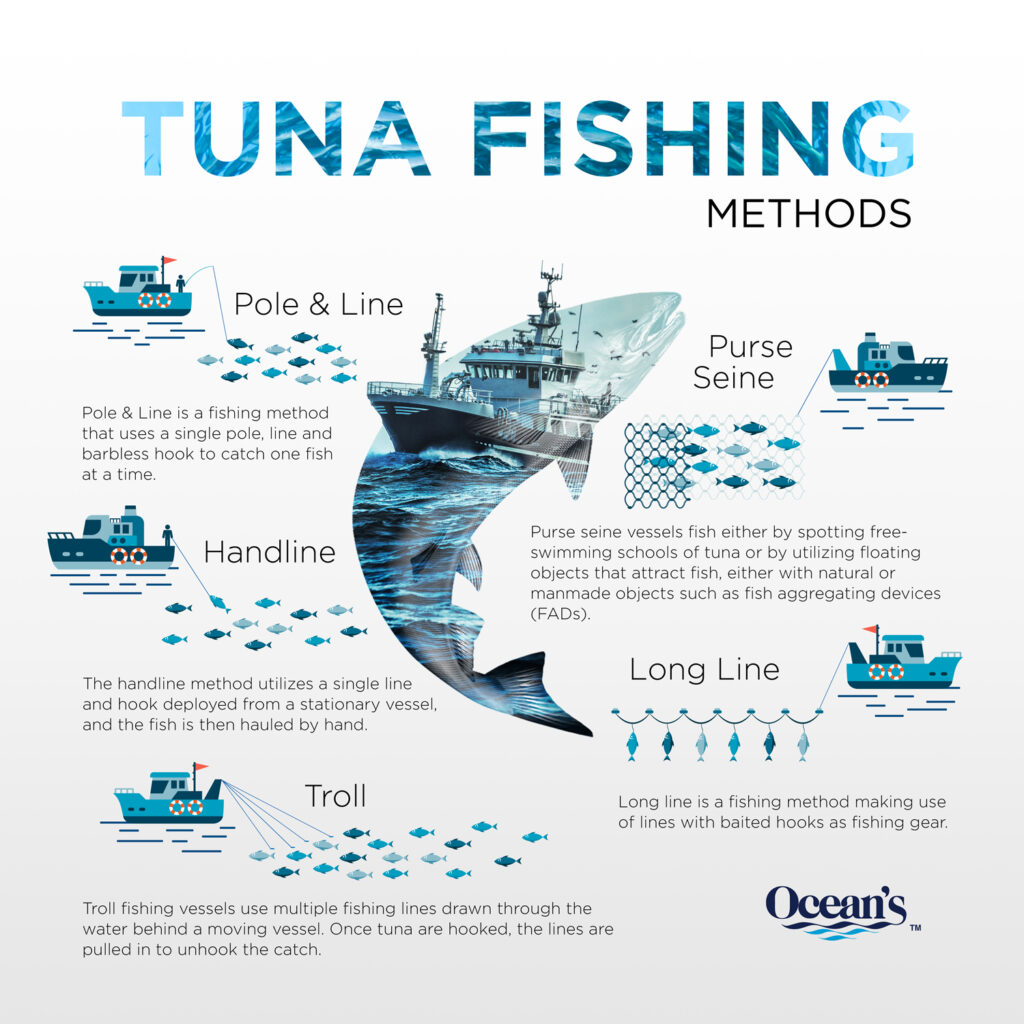

However, there’s a silver lining. Tourism doesn’t have to be a one-way street of destruction. By adopting sustainable practices, tourists can become eco-warriors and contribute to reef conservation efforts. One way to do this is by supporting eco-friendly tour operators. These responsible businesses prioritize reef-safe diving practices and use mooring systems instead of anchors, protecting reefs from major physical damages. Tourism businesses also have the unique opportunity to educate tourists on proper reef etiquette and limit the number of people near the reefs at a time to minimize crowding and associated stress. Tourists may even be asked by their diving or snorkeling guides to use reef-safe sunscreen.

Tourism and fishing businesses also have the opportunity to influence behavior and contribute to the preservation of their ecosystems directly through reef restoration projects. Coral rehabilitation, larval seeding, and coral transplantation allow locals and tourists alike to participate in reef preservation, while still being able to enjoy the scenic views and ecosystem services coral reefs provide. Additionally, tourists may wish to make financial donations or volunteer, both of which have significant impacts on the future of these vital ecosystems. Finally, spreading awareness about sustainable tourism practices is crucial. As more people understand the challenges coral reefs face, the greater the collective impact.

Saving the reefs may seem like a daunting task, but there are many options in the tourism sphere alone that provide hope for the preservation of these underwater wonders. The success of these potential solutions, however, will depend on the coordination of efforts between states, NGOs, and private businesses.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/f3/a6/f3a6fe69-8562-490e-82b8-1f47d7440842/ap_17322182296131.jpg)