Here is a contextual story in the Valley that places a systemic perspective of those involved in police corruption as money and drugs cross in greater numbers the Rio Grande. Questions keep getting closer to Hildago County’s Sheriff Lupe Trevino with the recent indictment of Sheriff’s Commander, Jose Padilla as detailed in this story from the Houston Chronicle. County and city law enforcement have been indicted by Federal authorities in a pattern of involvement with the drug trade for over a decade.The reasons include the proximity to Mexico, the land routes of contraband through these counties and the existence of family and friendship ties.

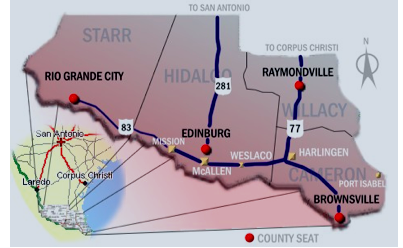

Hildago’s population is just over 800,000 and adjoins Cameron County to the east that has a population of 415,000. McAllen in Hildago and Brownsville in Cameron are “twin cities” with Reynosa and Matamoros, respectively. A third border town with twin cities is Laredo and Nuevo Laredo in Webb County with a population of 260,000.

The three Mexican cities are in the State of Tamaulipas which is a major route for drugs from Mexico and immigrants from Central America headed to the United States. For the last decade two Cartels, the Gulf and the Zetas, have fought each other and the Mexican government for the control of the state and its roads and railways to move contraband. State and municipal police are frequently corrupt or impotent in dealing with the far wealthier and powerful cartel forces.

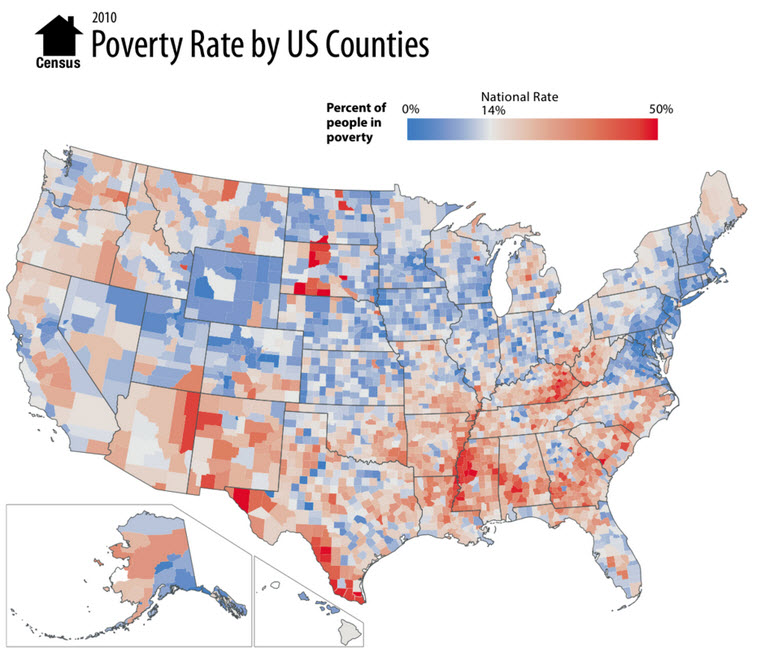

Poverty is endemic in the Valley but far more so across the Rio in Mexico. The Valley is the poorest part of Texas as well as in the United States with reported unemployment averaging over 10 percent. Coupled with very low education levels, low wage jobs and population growth, it is a region readily susceptible to promises of quick money and corruption of officials.

But in Mexico the unemployment rate is 50 percent in many areas. With a young population Cartels have many ready recruits and the proximity of the continent’s greater base of drug customer draws many into the Valley to move drugs north.

Slippery slope of crime is mapped in Valley

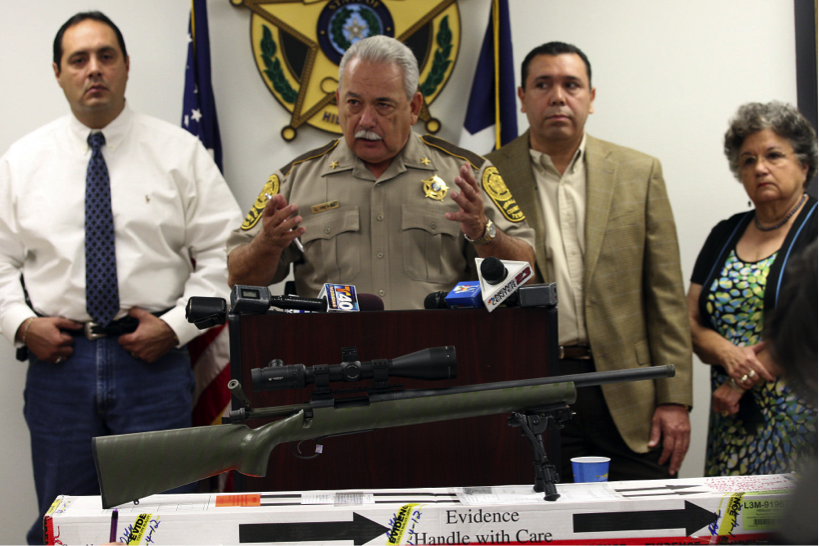

Joel Martinez, AP

Jonathan Treviño (left), seen walking with attorney Robert Yzaguirre, is the son of Hidalgo County Sheriff Lupe Treviño.

By Jeremy Roebuck

August 4, 2013

It started with a political donation and a request for a small favor in return.

That simple exchange gradually would lead James Phil “J.P.” Flores into a relationship with narcotics traffickers, the former Hidalgo County sheriff’s deputy said as he testified last week in the trial of a colleague accused in a wide-ranging drug conspiracy. A local smuggler with deep pockets knew Flores faced pressure to raise money for his boss’ campaigns. He offered the deputy cash. When the trafficker later asked him to check a few license plates, the request seemed harmless enough. It was the least he could do, said Flores, who pleaded guilty to his own role in the conspiracy earlier this year.

“We were using him,” he said. “But he was using us, too.”

That relationship, detailed in testimony at the ongoing trial of former sheriff’s Deputy Jorge Garza, lays bare a frequently overlooked aspect of how corruption often takes root in Rio Grande Valley law enforcement. In a region where sheriffs, prosecutors and local officials fall with disturbing regularity to federal charges, the descent from upstanding public citizen to corrupt official rarely occurs in one giant leap.vMore often, said Anthony Knopp, a professor emeritus of history at the University of Texas-Brownsville, that slide occurs at a creep.

“There’s a susceptibility there to accommodate people that are compadres or family and who may be doing something on the questionable side of the law,” he said. “But once you start down that path, each new favor tends to push the line a little further.”

Jerry Lara / San Antonio Express-News

Jerry Lara / San Antonio Express-News

Although his son has admitted his guilt, Sheriff Treviño (at lectern) has not been charged and repeatedly has denied any knowledge of the Panama Unit’s illegal activities. In Flores’ case, requests to scan license plates became plots to guard drug loads and schemes to rip off competing traffickers, the former deputy said. Eventually, Flores, Garza and seven other law officers, many of them members of a multi-department narcotics task force known as the Panama Unit, found themselves in handcuffs. All but Garza, a retired warrant officer and a man prosecutors have described as a bit player, pleaded guilty to accepting bribes and guarding drug shipments and stash houses.

And as witness after witness took the stand at his trial last week, their testimony detailed tight family connections, pressures at work and longstanding personal relationships that led them to the wrong sort of people. Their stories described a line between the law-abiding and law-breaking that’s often frustratingly hazy. Garza’s own sister, Alma, is a prominent local defense attorney and perennial candidate for district attorney on county ballots.

And testifying Wednesday, Fernando Guerra Sr., Flores’ smuggler contact, said he often stored cocaine stolen by the deputies at the home of a colleague’s girlfriend.

Federal prosecutors alleged in 2008 that Starr Sheriff Reymundo Guerra struck up a relationship with a Gulf Cartel operative. The woman, Aida Palacios, had once worked as an investigator for the county’s district attorney. And her aunt, Mary Alice Palacios, a one-time justice of the peace, often stopped by to visit. Asked whether the ex-judge had ever seen the cocaine her niece allegedly stored, Guerra testified that she did. Mary Alice Palacios’ attorney later declined to answer questions about Guerra’s statements.

Nowhere, though, have those family bonds cast deeper shadows than with Jonathan Treviño, one of Garza’s co-defendants and the son of Hidalgo County Sheriff Lupe Treviño. The younger man has admitted his guilt; the elder has not been charged and repeatedly has denied any knowledge of the Panama Unit’s illegal activities. Since his son’s arrest, the sheriff has walked a tightrope expressing personal support for his son while loudly condemning his bad acts.

“The actions of those deputies — including the actions of my son — are just despicable,” he said in an interview Thursday. “It’s just something you don’t do as a law enforcement officer.”

But those denials haven’t convinced the sheriff’s critics, who question how he could be unaware of the corruption rooted within his own department and family. That suspicion, said Knopp, is born out of the prominence that family bonds and small favors have played in the recent history of the region’s fallen lawmen.

A string of convictions

A bribery scandal involving a drug trafficker and conjugal jail visits ended the career of Trevino’s tough-talking predecessor, Brig Marmolejo, in 1994. Federal prosecutors charged Sheriff Gene Falcon in neighboring Starr County four years later for taking bribes.

And a decade later, another Starr County sheriff, Reymundo Guerra, found himself in the unwelcome spotlight. Federal prosecutors alleged in 2008 that Guerra struck up a relationship with a Gulf Cartel operative in the neighboring Mexican city of Miguel Aleman. The sheriff later admitted in court that it began with small requests for information delivered over family barbecues and eventually grew to more.

But Alonzo Alvarez, a longtime friend and retired schoolteacher, testified at one of the sheriff’s court hearings that year that he had little trouble reconciling the family man and career law enforcer with the corrupt cop who helped bungle ongoing drug investigations and gave up the names of informants working with police. Alvarez told the court that growing up, he and many of his friends, relatives and neighbors turned to smuggling or knew others who had as a way to make a living.

Asked by the judge whether he was admitting on the stand to involvement in drug trafficking, Alvarez shrugged and replied: “If that’s what you want to call it, then, I guess so.”

Aaron Nelson of the Rio Grande Valley Bureau contributed to this report.

jroebuck@express-news.net

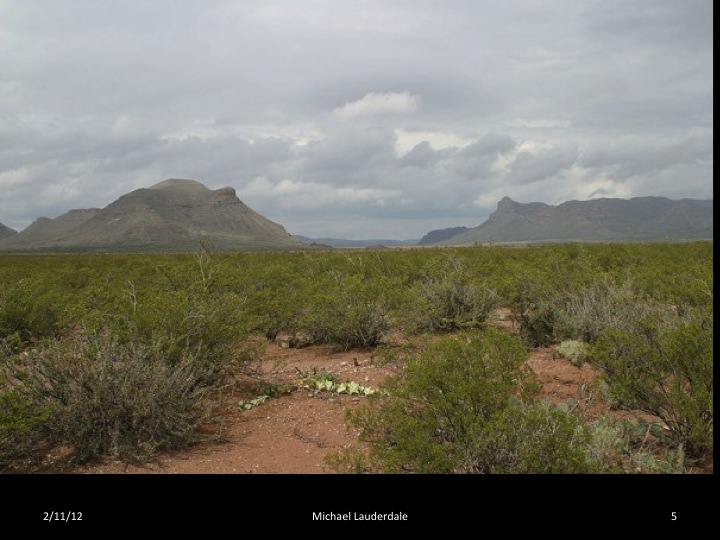

Countryside in western Tamaulipas