Why A Dying Elephant?

For decades the nation of Mexico has been barely on the radar screen of the United States. But in recent years attention has begun to be paid to the border of Mexico. Part of the reason for the attention is the cascading violence that began in the northern cities of Mexico and now has clearly spread throughout Mexico. Less recognized is the “fall out or spillover” occurring in the United States from conditions in Mexico. The violence has reached such a crescendo that discussions have begun about whether or not Mexico is a failing state or, most serious, a failed state. Failed states exist when the control of the central government collapses and smaller units such as tribes, regions and families become the paramount in-stitutions. Current illustrations are Somalia on the Horn of Africa and Yemen near the oil fiefdoms. His-tory is filled with examples as in time all states failed and among the prominent in our intellectual histo-ry is France in the late 1770’s, the Chinese under Chaing Kai-shek when faced with the Maoist Revolu-tion and the Soviet Union in 1991.

We examine the conditions that exist that lead to state failure as well as the markers of a failed state in Mexico.

The title of the presentation, “The Dying Elephant”, comes from conversations held over the years by Americans that work with Mexico, most frequently from the State Department. When relations with Mexico would reach a frustrating extreme, a seasoned employee, “an old hand” would caution walking away and would note that the alternative is a “dying elephant” left on the American doorstep. That is the consequence of a failed state in Mexico for the United States.

Prospects For Mexico

The purpose of this narrative is fourfold. The first is to provide some facts about the border as well in the two nations. The second is to examine aspects of their relations and activity that give rise to con-cerns along the border as well as frequent misperceptions on both parts. Third, is to forecast likely con-ditions along the border as well as to define forces within each country that manifest themselves in each country and configure border relations. Fourth is to estimate the conditions and the degree that Mexico is tending toward a failed state. A separate article will examine steps that can be taken by each individ-ual country, Mexico and the United States, jointly and separately that could reverse this progression to-ward a failed state.

Several facts at the start will help to understand each country and why tensions arise. America is the world’s largest economy both in terms of production and consumption. Its economic activity affects the whole globe and its interests and military presence have become those of an empire. Mexico has grown into a large economy, as well, ranking as the 12th or 13th largest in the world and in the whole of North and South America. The United States, Mexico and Brazil are far and away the largest economies with the most advanced communications and transportation systems. Canada and Argentina are equally ad-vanced but far smaller in terms of population.

Understanding The Border

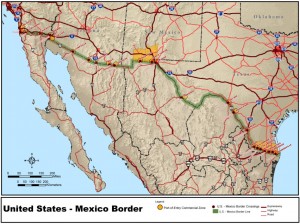

The United States and Mexico share a 2000 mile border with more than half, about 1200 miles, between Texas and Mexico. There are four Mexican Border States across from Texas: Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nue-va Leon and Tamaulipas. Both nations are among the world’s most populous with Mexico having about 115,000,000 and the United States, 310,000,000 people. America’s population is substantially older with a median age of about 36.2 years and, by contrast, Mexico has a median age of 26.1 years. Ameri-ca is wealthy and well-educated while Mexico is relatively poor, less educated and needing education resources.

An understanding of the border between United States and Mexico is advanced by examining a map of the two countries along the region where they meet. From the far western edge in California where San Diego and Tijuana are about 20 miles apart, the border extends eastward until one reaches the Gulf of Mexico and the cities of Brownsville and Matamoros separated only by a narrow band of water, the Rio Grande. It is useful to use the metaphor of geology and think of two large tectonic plates that are collid-ing at the Texas-Mexico border. The northern plate is the United States and the southern plate is Mexi-co with the Rio Grande as the subduction zone where the two plates collide. Energies from this collision then radiate both north and south for at least 200 miles. Such a metaphor helps us to understand that cities like Houston, San Antonio and Austin in the United States and Matamoros, Monterrey, Durango and Chihuahua in Mexico experience the perturbations from these collisions.

The land, itself, is a high arid desert ecology that does not permit intensive agriculture but rather is best used for grazing sheep and cattle. The one exception is the region along the Gulf Coast that can have heavy rainfall and is often exposed to hurricane- based storms. Because of the ecology, historically, the population has been sparse but the pull of the markets of the States has changed that centuries-old real-ity of large ranches and small villages in the last 30 years. The entire 200 miles zone on either side today has approximately 20,000,000 people with almost all in urban areas. Far higher wages exist on the Unit-ed States side incurring continual Mexican migrations to the north. Indeed more than ever in its history northern Mexico is oriented toward the United States like the needle of a compass to its north pole!

Mexican History

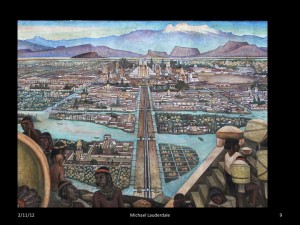

When European explorers reached North and South America in the 1500’s, they encountered not empty lands but substantially populated villages and highly varied, complex cultures occurring irregularly across both continents. In the Central Highlands of Mexico, they found the Aztec culture then about 300 years old and existing as the region’s most powerful colonial entity subjugating other Indian tribes miles to the north and south and east to west from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific.

In time it was discovered that the Aztecs had been preceded by three or four other older cultures dating back probably 2000 years. The Aztecs, themselves, appeared to have migrated around 1200 AD during a great drought from the Four Corners area of the American Southwest arriving in the Valley of Mexico initially as a poor, small tribe of hunters and gathers. In about three centuries they achieved colonial domination in the Valley of Mexico using aquaculture in the great lake at the center of the Valley establishing the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan and having a population of 40,000. Thus the Aztecs were at the height of their empire about three centuries old when European contact occurred. Europeans learned of the Aztecs through the reports of Hernan Cortez, the Spanish conquistador who invaded the Aztec empire in 1519, and that Indian empire was, simply, the latest in an ancient world of conquest, migration and conquered peoples in the Americas. The war against the Aztecs by Spain lasted about 50 years resulting in a new colonial power from Europe, the complete destruction of much of the Aztec culture and a population reduction from approximately 10,000,000 in Mexico to 1,000,000 Indians by the 1700’s.

Patterns of Oppression and Revolt

Mexico then saw for the next 450 years from first European contact, oppression of the native popula-tions and successive revolts against Spain, France, large Mexican landholders and the Roman Catholic Church and as late as the 1940’s efforts to expel foreign interests, particularly American and British oil companies. Thus the history of Mexico is one of repeated wars and the imposition of one political pow-er violently over existing societies. Much of the culture and political discourse of Mexico, even today, reflects concerns of domination by foreign interests and efforts by the Mexican population to secure independence.

This history also illustrates, returning to the geological metaphor, that change in Mexico comes not smoothly and progressive but rather through sharp discontinuities, earthquakes. Indeed Mexico sus-tains a revolution about every hundred years as it betrays a brittle response to change pressures.

Aided by horses, armor, cannon and subjugated, exploited Indian tribes ready to join efforts to destroy the Aztecs, the Aztec empire fell abruptly in Mexico City and then gradually in the outlying areas over the next fifty years.

Spain then spent the next nearly 200 years consolidating the colony of Mexico seeking to extend its con-trol into South America and north from Louisiana to the Pacific Northwest. It sent armies accompanied by traders to secure wealth for Spain and Catholic priests to convert the residents to loyal subjects of Spain as well as providing vast agricultural and mining resources to Spaniards choosing to come to the New World. The years were filled with bloody conflict and prepared the stage for successive revolts in these conquered territories over five centuries.

The First Attempt At Mexican Independence

The next most significant revolt after the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs in Mexico began on May 5, 1810 through the efforts of a Roman Catholic priest, Father Juan Hidalgo. Outraged at the treatment he saw of the Indians and Mestizos (the offspring of Spanish men and Indian women), he urged them along with Spaniards born in Mexico (Corriolos) to rise up against the European colonial power. Mexico like Bolivia and Venezuela to the south was moved by the forces of the Enlightenment and Reformation be-ginning in Europe that had stripped the British colonial powers of the American Colony. That American Revolution created the first full expression of those movements of a society freed of the world of the ancien regime where power was vested in hereditary royalty, landed gentry and the Roman Catholic Church. Central to the appearance of American Exceptionalism in the 1700’s is the sense of the authority of government rooted in the consent of the governed and that consent expressed through voting among other mechanism of social participation including free assembly, a free press and government structures representative of the will of the populace.

Much of Latin America sought similar freedoms and yet those lands like Mexico saw much of their revo-lutions’ promises stalled or reversed. Father Hildalgo was executed by government forces and set a pat-tern in many successive revolts with the untimely deaths of revolution heroes. But some sense of de-mocracy grew in Mexico with Spain agreeing to its independence in 1821 and reached its height in the 1860’s with the election of Benito Juarez. During the years from Mexican Independence until the 1850’s wars occurred with Texas and then the United States that severed the claimed territories of Mexico in much of North America. France attempted a re-conquest of Mexico with an invasion of Mexico City in 1863 but was repulsed by 1864. Then a brief period of elections followed. However traditional forces regrouped and installed Porfirio Diaz via election, who ruled as a dictator though formally elected as President from 1876 to 1911. The agricultural and banking reforms achieved under Juarez were com-pletely reversed and by 1910 a few land owners and once again the Catholic Church owned most of the land in Mexico leaving 90 percent of the people landless.

During most of the years of Mexico’s existence the ownership of land was crucial as little factory or trade work existed and people secured their existence by farming and animal husbandry. In many parts of the country the land was not surveyed, registered and owned but rather held as a communal proper-ty with rights to use coming from tribal membership. European activities including property rights of land ownership and associated taxation were alien to the bulk of the Mexican population and in the ear-ly 1800’s and then again after the 1860’s saw land ownership concentrated in the hands of the few, the establishment of a landless peasant class with rights less than under a feudal system.

Repeatedly in the 19th and into the 20th Century revolutions would attempt to meld the various groups in the Mexican population into a common national vision.

Cultural and Economic Fundamentals of The Modern Mexico

The most recent significant Mexican revolution was between 1910 and 1920. This revolution began not in Mexico City but in the north, particularly the state of Chihuahua led by Pancho Villa and in the south by Emiliano Zapata. There were other leaders in this revolution but these two are significant in that they were viewed as coming from the peasant class, uneducated, illiterate and from the ranks of the Indian and Mestizo population of Mexico. Though both were killed and in treachery not combat at the end of the conflict, the revolution once again broke up large land monopolies by Mexican wealthy, remaining European families and the Roman Catholic Church ushering in the modern Mexican State as it exists to-day.

A final paroxysm of the 1910 Revolution came with the Cristero War in the late 1920’s. It was an effort by conservative Catholics in states northwest of Mexico City, Jalisco and Guadalajara, to reverse Federal government actions against the Catholic Church. The Roman Catholic Church has long been a controver-sial institution in Mexican culture. Forced conversion by the Church of Indians began with the Spanish conquest though at other times such as the efforts by Father Hidalgo, the Church was a mechanism of efforts to better the conditions of the poor and landless. But during much of the 19th Century the Church worked hand-in-hand with the wealthy and politically powerful and, itself, became a wealthy landown-er. Thus in the 19th Century the Roman Catholic Church appeared in Mexico as a powerful and conserva-tive land and wealth monopoly much as it was viewed in the 1770’s in France, Italy and Spain. Priests and the Church, itself, were among the focus of the 1910 Revolution and resulted in a sharp reduction of wealth holdings and power by 1920. The Cristero War was an effort to reverse that situation but ended in defeat though with the loss of 90,000 lives. An aftermath of this war was an even sharper curtailment of the presence and power of the Catholic Church with the Church being forbidden to own property, run schools and for priests and nuns to appear in public in clerical garb.

In the soul of the Mexican culture and state are concerns about foreign domination and wealth concen-tration. These concerns were expressed in the 1930s and 1940s with the expropriation of American and British Oil properties in Mexico by then Mexican President, Cardenas. During those years and significant throughout the 20th century are Mexican involvements with Marxist perspectives and in many ways the monopoly of the state in much of Mexican society in the 20th Century shows Marxist as well as state-controlled monopoly capitalism.

The experiences of Mexicans across hundreds of years extending far back beyond the Spanish conquest are those of cultural contact, war and conquest. Heroism and betrayal of the hero are common themes. Revolutions succeed, heroes are assassinated and dark powers reassert their control. Social classes, ra-cial lines and exploitation are recurrent themes. Rather than building an optimistic culture with a belief in successful social engagements it is a cautious culture, often fatalistic and one where only the family exists as a true and safe harbor. Family ancestors are revered and remembered and the individual is for-ever faced with the security of family and the risks of the outside world. These cultural memories are part of the psychology of the individual Mexican and play a critical world in defining Mexico today and to varying degrees the thinking and behavior of those with Mexican heritages in the United States.

Mexico in The Popular Mind

Photographs, paintings and posters help illustrate the popular notions of Mexico, today. The reality of the Mexico we know bears a heavy imprint of the past including the means Cortez used to overthrow the Aztec state, the interplay of Indian and European cultures, the march of peasant armies for land re-form and against foreign domination, and ancient symbols of the past like Mayan Temples in the south-east of the country. The past shapes the modern including the national cathedral in Mexico City built with stones from a ruined Aztec sacrificial pyramid, the statue of the angel in Mexico City, and enduring regional flavors such as native dress in Guadalajara, bullfights, sombreros, the Day of the Day remem-brance and a welcoming poster from the government of Mexico with a saguaro cactus, sombrero, sera-pe and guitar! Beneath the mariachi band and vaqueros, is an aerial photograph of Mexico City, one of the world’s great cities of more than 25,000,000 and some of the most beautiful beaches in the world on the western coast. This is the Mexico of the popular conscience in the world and the face Mexico wants the world to see.

Mexico: The Hidden View

But there is another Mexico emerging from economic growth, more democracy and the vestiges of a middle class. It is a country of singular monopolistic institutions, powerful regressive unions, authoritari-an leaders, extremes of wealth and grinding poverty and exploding passions. Long the dominant and autocratic Mexican political party, the Party of the Institutionalized Revolution, the PRI, lost its hold on Mexico at the end of the 20th century and genuine democracy began to appear in such persons as Vicen-te Fox and the National Action Party, the PAN electing in 2000 the first Mexican President in modern times that was not a creation of the PRI.

While corruption and organized crime have long been a feature of Mexico what was less known or popularly acknowledged in the rest of the world was the complex intertwining of the corruption with the agents of the Mexican State, itself. From the local cop who required “mordita” for to fix a traffic ticket to arrangements for regulated alcohol, prostitution and drugs in certain restaurants, bars and clubs of the town to the cabal that choose the nominee for the PRI every 6 years for the Presidency were all an enduring feature of Mexico since the 1920’s.

The Soul of 20th Century Mexico: The Party of the Institionalized Revolution

However the breakdown of the control of the single national party provided an opportunity for orga-nized crime, the Mexican Cartels, to grow explosively. To understand the cartels of today we must exam-ine the history of Mexican politics. For decades the PRI maintained a vertical grip from remote villages to Los Pinos, the Mexican White House. At the local level towns would have a designated “red light district” where contraband was available including prostitutes, drugs and gambling. Operators would “license” the business through the local PRI representative or in some cases, law officer. The law and the PRI were often indistinguishable. To get almost anything accomplished in Mexico required somehow including the PRI. Larger businesses such as the telephone, television, energy and water utilities, railroads and airlines were simply government-owned enterprises. The most profitable then and still today is PEMEX, the oil production, refining and retailing monopoly. The service fields including teaching, health care, hotel and restaurant workers are controlled by unions and part of the PRI structure.

This control of the state began in the 1930’s and reached its zenith in the 1980’s. However several forces began to demand change and to lessen the control of the centralized Mexican government. One was simply the need to make the society more productive and innovative. A second was the increased awareness of the Mexican population, especially the emerging middle class, that the United States, Eu-rope and Japan, all with higher standards of living accomplished some of those standards via a more open marketplace of ideas than could occur than in the fixed political arrangements of Mexico. Mexico was also influenced by the collapse of the Berlin Wall and then the Soviet Union in 1991, a paradigm of a command and control economy much as Mexico was. The appearance of the PAN election, the decline of the PRI was also the beginning of an increase in private groups creating enterprises not the Mexican State, not the PRI.

The First Democratic Current Since the 1910 Revolution

Visible political change began to occur in northern Mexico in border cities like Juarez during the 1980’s and 1990’s. The city long closely tied to El Paso began to develop political practices influenced by Ameri-can thought. The mayor in 1983 Francisco Barrio was the first PAN mayor in Juarez and of any major Mexican city and later became the Governor of the state of Chihuahua. Other large landowners in bor-der cities became attracted to the changing regulatory relationships between Mexico and the United States and began to build maquilas (assembly plants) that could use cheap Mexican labor to assemble items for duty free export into the United States. Jaime Burmudez, one of those landowners became a leader in building these plants and served as Juarez Mayor after Barrio. Though he was aligned with the PRI, his ties in El Paso accelerated an electoral process in Mexico that drew from American culture of some level of competition among candidates and parties as well as a far larger private as compared to a public sector.

By 2000 the climate in Mexico had moved strongly away from the appointed Presidential candidate of ten decades of the PRI rule and for the first time an alternative party, the PAN, mounted a strong cam-paign and elected the President, Vicente Fox. This Presidency then followed by a second PAN, Presiden-cy, Felipe Calderon, would break the old arrangements of petty crime, organized crime and perhaps, in time, political ties with the wealthy oligarchy of Mexico.

The result of the PAN election was part of a civic revolution in Mexico, a revolution long delayed and thwarted. It began with the 1810 Revolution that overthrew Spanish control but failed to establish a democracy as Mexican patriots looked to the United States as a model. European powers, Spain and France, large property owners and the Roman Catholic Church thwarted the Revolution and reasserted a Mexico as powerless, peasant regime. Electoral reform came again in mid-century with the election of the only Mexican President from the indigenous population, the Indian Benito Juarez. For a few suc-ceeding elections democracy flourished but with Porfirio Diaz, it retreated into a dictatorship with the Church and a few large landowners partners again in total control. By the start of the 20th Century 90 percent of the population was in dire poverty existing as peons on lands owned generations ago by their forebears but now by less than a hundred families and the Catholic Church. The 1910 Revolution again was thwarted by the PRI that under the label of being a continuation of the Revolution restored the dic-tatorship by a few and the impoverished and control of the Mexican population.

The PAN victory in 2000 was a renewed attempt for a culture trying to break free from dictatorial con-trol. The victory inevitable came into conflict with many of the structures of the iron hand of the PRI and that included corruption in the government as well as criminal gangs in many areas of Mexico but great-ly in the northern cities near the American border.

Unintended Consequences of a Democratic Mexico: The Rise of the Cartels

The efforts to break with the past have come quickly and in many dimensions with frightening effects. In 2007 Mexican President Felipe Calderon declared war on the Cartels and from 2007 to 2010 there were over 35,000 violent deaths in the war against and among the Cartels.

To understand the growing waves of violence in Mexico and the implications for the United States we must look at three factors in Mexico and the United States. These are the economies, demographic fea-tures, and cultures of each, but with the focus on Mexico. Unlike in all of the decades of the past Mexi-co’s economy is integrated with the world. Thus Mexico will be affected more than ever in its history by events in the United States, Europe, Asia and the Middle East.

Major Mexican Economic Engines

Mexico is the third largest economy in the Americas behind Brazil and the United States. It is rich in agri-cultural, fishing and mining potentials with a young but not highly educated workforce. There are five major engines that vary in terms of the numbers employed, gross revenues, percentage of profits and source of control of the sector. Below are the major engines and the Table below outlines the economic impact of each.

1. Export of Crude Oil Primarily from the Bay of Campeche

2. Export of Temporary Workers 10 to 30 Million

3. Tourism and Services More than 70 Percent of Employment

4. Assembly Manufacturing (Maquilas)

5. Drugs, Human Trafficking and Extortion

Probable Profits From Major Engines

Export Item Dollar Amount Profit Percentage Profit

1. Petroleum $130 billion 10% $13 B

2. Tourism $185 billion 8% $12 B

3. Visiting Workers 20 million people $300 billion 10% $30 B

4. Manufacture and Assembly $100 billion 15% $15 B

5. Narcotics $50 billion 80% $40 B

The Mexican Oil Boom

Mexico’s natural resources have long been a dominant feature of the country. Silver mines about two hundred miles north of the capital in the Sierra Oriental have been worked for more than 500 years and prominent fisheries on both coasts have supported great populations for more than a thousand years. Trading routes in turquoise, coral, gold, silver, seashells, birds and animals have been traced from the Pacific Northwest, the American Southwest, through the Valley of Mexico to Highlands of Guatemala and El Salvador since 2000 B.C. The most recent natural resource wealth was the discovery in the late 70’s of vast offshore oil deposits near Veracruz. This oil that is owned and controlled by the state mo-nopoly, PEMEX, created the first middle class in Mexico starting with the employees of PEMEX providing salaries multiples of what other sectors earned and including retirement and health benefits with free or low cost housing. The PEMEX employees set a pattern, a goal for the middle class of Mexico.

Using Oil Wealth To Grow The Population

These oil riches caused an explosion in the wealth of many Mexicans and the Mexican State. Part of the state’s response from the oil export earnings was to increase the subsidies on basic agricultural items such as beans, rice and corn. It used the earnings to lower the cost of food and enlarged a policy began in the 1930’s to encourage population growth in Mexico as well as ensuring the support of the poor for the ruling political classes.

For centuries Mexico has feared invasion and domination by an external enemy, a fear based on an event that had been repeated many times. In the 20th Century this became fear of the United States and the concern that Americans would annex the largely vacant areas of northern Mexico as part of a Manifest Destiny to expand America. The evidence was there as the United States had done that in the 1800’s. Mexico’s response was to encourage big families with the assumption that large populations in the northern states of Mexico would be a barrier to American annexations. A large and young popula-tion has become an important feature of modern Mexico.

Mexico Becomes Urban

Modern Mexico is characterized by the changing population distribution in the country. For centuries it was a rural land with only one large population center, Mexico City, always being less than 100,000 peo-ple. However, through the last 30 years the Mexican population has moved to urban areas growing the Mexican Federal District to more than 25 million and several cities along the border with the United States to a million or more. Mexico, always a rural nation, now has become one where only 20 to 30 percent of the population live on and are supported by the land!

The Mexican rural population was self-sufficient in food, housing and utilities. Housing was rudimentary; water came from streams or hand-dug wells and waste disposed in dry toilets. Gardens and domestic animals provided the food supply and maintaining all of this was the definition of work for the rural res-idents.

The Search For Jobs

Urban populations participate much more fully in specialization and an exchange economy and require jobs with food imported from the countryside. Thus, job growth became by 1980 a desperate need for Mexico in response to where the population lived. So desperate that Mexico did two things, one irre-sponsible and one heretical. The irresponsible was to urge Mexicans to leave Mexico but send money back to support families. Leave they did with more than 10 and as many as 20 million going to the Unit-ed States by late 2010. The heretical was to reverse the policy of forbidding foreign interests to own properties in Mexico as what was first a border assembly plan in Juarez became an all-out effort to get foreign manufacturers to locate plants in Mexico. These plants, at first, did not do major manufacturing but rather completed labor intensive assembly of parts manufactured elsewhere in the world and were called maquilas.

Industrialization Via The Maquilas

The maquilas provided three desperately needed resources for Mexico. One was capital investment that built physical plants, provided sophisticated manufacturing tools and created a tax base to extend utili-ties and transportation to the factories. This was an important gain for Mexico as estimates in those years was that it required a dollar capital investment of $250,000 to create each factory job. The second resource was the job, itself, and the earnings it provided for an urban worker. The job was what one must have to survive if one is not living in rural Mexico. These jobs also provided much better wages and a standard of living than was available in the rural areas. These attractive jobs would have another unan-ticipated effect and that was to accelerate the movement of rural labor to the cities. The third resource was the training and education that a foreign manufacturer brought to the Mexican worker. Workers learned how to operate and maintain a variety of mechanical and electronic machines, the routines re-quired of factory work, being supervised and learning to supervise; all of the complex of knowledge, atti-tudes and skills for successful performance in a modern workplace. For many with only about 6 years of education and environments with little technological features it was a cultural transformation.

Mexicans Working in The States

Working in the United States, where almost all of the surplus workers, went was a similar transfor-mation. Food processing, construction and service work absorbed most of these 10 to 20 million work-ers as the agricultural worker pipeline was already full. From 1980 until 2007 the United States was booming and the Mexican workers spread out far beyond Texas and California settling in cities and small towns all across the United States. Most of the workers were males and would send money back to wives and/or parents in Mexico and make treks back each year or so to visit families. While they often lived in proximity to other Mexicans they were influenced by the American culture and language and like the factory worker in the maquilas were a different sort of person than the humble, conservative, reli-gious and cautious Mexican farmer. Most developed some facility in English and increasing reluctance to return as well as fewer ties with homes and relatives in Mexico.

The females that made the journey changed more than the males. The rights of women are far less in Mexico and the young Mexican women rapidly incorporated views of American women and their rela-tive independence of males in where to live, shopping and entertainment. If they had children, they found that the American school system with children in school for 8 hours rather than 4 as would often occur in Mexico, meant the ability to create and sustain an identity beyond a mother at home. Like oth-er American women, they would develop dual identities of workplace and home.

Working in Tourism

The expanded labor force in tourism changed the worker far less than those working in oil or the middle class professions made possible by the oil wealth. Being a waiter, maid or maintenance worker in a hotel provided cash income but not the margin of income or the skills to change the worker.

Roots of the Cartels

The sixth area of significant income for Mexico is activities associated with the movement of illegal drugs increasingly controlled by organized crime, the cartels, and rapidly growing ancillary crimes of kidnap-ping, extortion, cybercrime and theft. Most of these activities had their initial greatest growth in cities near the American border.

Tijuana and Juarez were the early most prominent. The two cities, in both cases, had organized crime units that went back to the era of American alcohol prohibition and supplied illegal alcohol as legal drink in their bars and as a source of shipping alcohol into California and Texas. Heroin was also available as Chinese immigrants grew opium poppies in the western Mexican states of Sinaloa, Michoacán and Guer-rero during the 1940’s to supply American medical needs when the war in the Pacific interrupted sup-plies from south Asia. From the 1920’s until 2000’s this illegal activity existed under the control and like-ly franchise-like arrangements with the PRI including local government officials. However by the late 1990’s drug consumption in the United States was drawing greater production in Mexico and young farm workers were learning that they could undertake the risks of smuggling marijuana and cocaine and make more in a trip than in ten years of farm work. As efforts to curtail the movement of cocaine in the Caribbean succeeded, much greater opportunities emerged for Mexicans to smuggle drugs across Mexi-co and then at the key border cities into the United States.

The business influenced the popular culture. A new form of music developed from the country corridos or cowboy ballads in the ranch culture and was called narcocorridos. Bands appeared with popular rec-ords that recorded some of the “daring do” tales of the young smugglers, their sudden riches which they used to purchase new pickups and SUVs and the much desired silver-plated .45 ACP as well as more formidable automatic weapons. The romantic ballads and bands began to serve as a recruitment vehicle for the growing cartels that were organizing the individual entrepreneurs into more focused and skillful smuggling operations.

Open Efforts By The Mexican Government To Curtail Cartels

Figure 6 Cartel Violence Using Psychological Warfare-Acapulco Fall 2010

By the 2000 elections the environment of the cartels began to change. The franchise arrangements that existed in some areas with law enforcement and in all cases with the approval of the PRI became unpre-dictable. The PAN presidency viewed those arrangements as both law violations and as a fund flow to PRI operatives and a threat to democratic institutions. By 2006 a second PAN President, Felipe Calderon declared open war on the cartels and initially focused force on Juarez. At the same time a struggle had begun between the long dominant Juarez cartel and a new force appearing from the west, part of the Sinaloa cartel.

For the cartels, control of key cities and sites in the cities is like a fast food business such as McDonald’s or Burger King seeking a key corner location or near an exit and entry ramp on an Interstate Highway. Location is nearly everything and it is for drug smugglers, too. Drugs, unlike the five other major sources of wealth in Mexico, have an astonishing ratio of cost of product relative to what it brings on the market and to those that sell. Estimates run between 50 and 90 percent profit! This means the business includ-ing the plazas are extremely lucrative and the cartels will and can spend heavily to seize and defend them against all comers, the Mexican authorities, rival cartels and the Americans. They will use a variety of tactics including psychological warfare such as brutally torturing, murdering and dismembering oppo-nents. They offer bribes to police and judges with the bribe and the warning of death if the person re-fuses.

Since Mexico City started the effort to shut down the cartels at least 40,000 have died. Most are said to be deaths among cartel members but thousands are innocent people and those that were criminals are not enough deaths in all likelihood to deplete the cartels. More than half the Mexican population is in its earning years and jobs are difficult to find. Much of the population is young, unemployed, limited in ed-ucation and skills, and willing to take risks. That is the advantage that a large youthful age cohort, a weak economy and an urban population provide the cartels in recruiting new persons to fill their ranks.

Oil Not Cartels -The Greatest Security Risk

But the cartels are not the most major security risk to either Mexico or the United States. For the United States the greatest risk is the loss of oil imports from Mexico. America imports 70 percent or more of the petroleum consumed and the trend increases as the economy grows and in-country reserves are natu-rally depleted. The largest source for imports is Canada from its oil sands, but an expensive source. The second source is Mexico. As the following table illustrates the other major sources are countries with high stability problems or countries not friendly to the United States.

The fragility of the Mexican supply, and it is very, very fragile, is not the disruptions posed by cartel vio-lence but the fact that Mexico is suffering rapid depletion of its largest oil producer, the Cantarell field. When it was originally mapped, it was thought to be similar to one of the great Saudi Arabian fields such as Ghawar that has lasted for decades. While the Mexican oil is similar in quality to low sulfur, high qual-ity oil from Texas, the field has proven to be shallow and Mexico is thought to lose its ability to export oil by 2014 to 2015. There may be other fields especially offshore to explore but PEMEX holds the monopo-ly and is notoriously incompetent and corrupt. If oil exports stop and they seem sure to do so, it re-moves the foundation of the middle class professions: medicine, nursing, teaching and higher education that have been built since the oil boom years of the 1980’s.

This creates a two-horned dilemma for the United States. Oil prices will likely rise and Mexico will grow more unstable with much greater attempts of Mexicans to migrate to the United States and cartels will use the chaos to strengthen. Moreover without oil export earnings Mexico will lose its major source of funds to import food to feed an urban population as well as to underwrite the middle class professions. Such forces only produce a more chaotic environment for the drug cartels to ply their trade.

Major Security Risks

United States Mexico

Must Import 70 Percent of Oil History of Revolutions

Has Major Empire Interests and Attendant Ene-mies Susceptible to Fragmented Border Great Wealth Disparities with Unemployment as High as 50 percent

Needs Secure Neighbor on the South and North Potential Food Shortages in Urban Areas

Failure of Oil Exports

Cartel Violence and Breakdown of Civil Order

Pattern of Development of the Most Significant Security Risk

Not Drugs But Interruption of the Flow of Oil

Next, the Decline of Mexican Oil Fields

This causes the collapse of the Mexican middle class paid by oil exports from PEMEX

These are police, government workers, teachers, physicians and nurses

Crude Oil Imports for U.S. (Top 6 Countries)

Country (Thousand Barrels per Day) YTD 2010 YTD 2009

CANADA 1,972 1,943

MEXICO 1,140 1,092

SAUDI ARABIA 1,080 980

NIGERIA 986 776

VENEZUELA 912 951

IRAQ 414 449

Darkness Along The Border

Texas shares a 1,200-mile border with Mexico that has a dozen legal border crossing points and a thou-sand that only the locals know. Trade is an important part of the crossings and has many old patterns and several newer. Among the older patterns are cow-calf outfits that move young animals born and raised on Mexican ranches across the border to be fattened and slaughtered for urban markets in Texas and then to the West and Midwest. Cheaper land and labor costs in Mexico makes this a viable business. Mexico does not have substantial grain harvests to “fat finish” cattle thus a few months in a feedlot in the grain-growing areas of Texas and the Midwest materially improves the meat for the American mar-ket. A less known aspect of the business is the trade back into Mexico of raw hides from Texas feedlots into states such as Leon in central Mexico where large leather processing industries turn the hides into items like shoes, belts, jackets and purses for French and Italian high-dollar brands that sell in the most exclusive stores in Rome, Paris, Tokyo, New York City, Dallas and San Francisco.

Field labor, as it has for decades, crosses from Mexico in the lower Valley to work citrus, onion, peppers and tomato fields and then north into the Midwest for other agricultural harvests including berries and apples. This is seasonable labor with migrants returning to Mexican farms and villages in the winter. In-variably some stay in the United States working in meat processing, restaurants, hotels, yard care and other occupations with low skill levels or no or limited union rules to restrict immigrant employment. These are the 10 to 12 million Mexicans that become Mexican Americans.

Several factors began to change this rhythm of trade between Mexico and Texas starting in the 1980’s. One derived from the creation of OPEC in the 1970’s as the United States moved from a net oil exporter to an importer. It was the first worldwide warning of Peak Oil and the slow shift from a century of drop-ping prices for all natural resources including food and water to one of rising prices. Coupled with this awareness of growing scarcity of oil was the discovery of a very large oil field in the Bay of Campeche off Veracruz in the Gulf of Mexico. While oil had been produced in Mexico since the 1920’s, this new dis-covery was a giant and appeared to rank Mexico with Saudi Arabia in terms of promising oil reserves; reserves that could fuel prosperity in Mexico for generations.

The final change of great consequence was the opening of political process with the timid initiation of a civic space to discuss alternatives in political leaders and parties. Since the late 1920’s there has been only one political party in Mexico, The Party of the Institutionalized Revolution, the PRI. There were lo-cal, state and national elections. But at the national level the PRI candidate always won. That candidate for the Presidency and for many other offices was selected every six years in a highly opaque process within the PRI. The PRI and the state were the same and the state owned everything including large businesses such as oil production, railroads, airlines, telephones, utilities, television and controlled the unions in all sectors. The political change that occurred was the capture of the Presidency by Vicente Fox of the PAN. PAN, the National Action Party, traces back to the Christeros Revolt in the 1920’s, who sought to reverse the 1910 Revolution and long reviled by the PRI as a predatory Catholic machine in-tended to return the Mexican middle class to peasants requiring priests and caudillos to lead them. The campaign of 2000 and the loss of the Presidency from the PRI was the first experience of electoral choice in more than a hundred years!

This brewing mix of Mexican events exploded in late 2007 with the international economic collapse. Oil prices dropped but more ominously so did oil production in Mexico. The bursting of the real estate bub-ble in the United States removed a huge source of jobs for Mexican men. The recession in the United States meant both fewer tourists coming to Mexico and far fewer purchases of the assembled goods in America that had engendered the Mexican boom in factory jobs. True unemployment has surged in Mexico reaching 50 percent in many areas.

Mexico is no longer a nation of small villages and farms where people stay home and tend gardens, chickens, goats and cows providing food for themselves. This is an urban Mexico where jobs are survival. The worldwide economic collapse has created a fundamental threat to the continuation of the Mexican state.

Economic Disasters Feed The Cartels

In this growing mire there remains one source of employment and that is associated with the illegal movement of drugs and people from Mexico into the United States. Here is a source of potential wealth that does not require extensive education, ownership of arable land or expensive equipment. To get started in the illegal drug business requires daring, ingenuity, the ability to make contacts in informal networks and a willingness to use brutality against one’s competitors and the police. And here is rough and tumble capitalism at its coarsest as young men, working solo and in gangs, compete to control the trade in moving drugs and people into the United States.

There are several major dimensions of this trade in Mexico. One is either growing the drugs including marijuana and heroin poppies, or importing meth feeder chemicals from China or transporting cocaine from Columbia, Peru, Brazil and Venezuela by land and sea in Mexico and along its coasts. The second dimension is staging the drugs or people to get them into the United States, and each requires securing control and monopolies of areas (plazas) in cities like Tijuana, Juarez and Matamoros where the bulk goods are assembled, American authorities are overwhelmed, tricked or bought off and then people and drugs are smuggled across. The third dimension is securing trading partners in the United States to re-ceive these imported goods. This may be individual dealers, unscrupulous employers, street gangs and, in some instances, members of Mexican cartels that have set up shop in the United States.

This market of illegal drugs and smuggled people is a huge market and the most profitable business in all of Mexico. It likely generates, annually, 40 billion dollars of profits and the profits are used to buy law officers, military personnel, judges and politicians. With these dollars military grade weapons are pur-chased including automatic rifles, grenades and combat vehicles. The profits are used to employ gun-men to protect the supply lines and eliminate competition. Gangs, termed cartels, have developed over the last 30 years that control the corruption in each region and yet compete with each other at the points of access to the American market. That is the reason that Juarez as an example has become one of the world’s most dangerous cities with 10 people killed daily in 2010.

An impressive share, I just given this onto a colleague who was doing a little analysis on this. And he in fact bought me breakfast because I found it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love reading more on this topic. If possible, as you become expertise, would you mind updating your blog with more details? It is highly helpful for me. Big thumb up for this blog post!

woh I am glad to find this website through google.

When I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove me from that service? Thanks!