President of Signature Sciences and Senior Scientist examine bio and other hazards from a fragmenting Mexican-American border.

Adam L. Hamilton, P.E., President & CEO

E. Norman Furley, Senior Strategist

Signature Science, LLC

22 July 2011

“Risk comes from not knowing what you are doing.”

Warren Buffett

The Problem

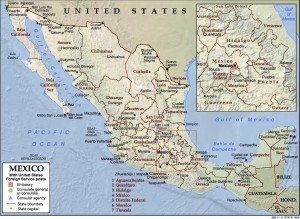

The risks associated with an increasingly unstable United States/Mexico border are growing national concerns in both countries. Headlines often include quotes from leaders of both nations that express outrage over reports of human trafficking, drug cartel activity, and the murder of civilians and government officials. And while the threats resulting from lawless behaviors are real, any consideration of the dangers that both nations face along the border is incomplete without a recurring, informed deliberation on the risks associated with the aforementioned threats and other hazards. Security and risk management along the U.S./Mexico border is a pressing issue that will require well-informed decisions to make effective mitigation investments. Until both countries and the affected states join in collaborative efforts to periodically assess the full spectrum of threats and hazards to identify and prioritize the real risks, it will be increasingly difficult to distinguish perceived or sensationalized threats (often highlighted in the news media) from hazards that are potentially catastrophic to one or both nations and develop the best risk mitigation plans for residents on both sides of the border.

Good Fences, Good Neighbors?

It has often been said that good fences make good neighbors. If the next door neighbor is the president of the Home Owners Association and a part-time dog breeder with four kids and a pool, a good fence will certainly make him a better neighbor. But this analogy implicitly assumes that only a physical and visual barrier is required and that the delineation of the properties is of manageable dimensions. If the neighbor is a nation with which you share a border in excess of 1,900 miles, establishing boundaries (not simply in the physical sense) and developing mutually-beneficial solutions becomes a much more difficult task.

For example, insidious non-violent hazards from biological pathogens (disease-causing organisms) present risks to public health and agriculture (plant and animal) that no practical “fence” can stop. Fungal diseases (Figure 1) that can damage or destroy important commercial plant products such as corn (Mexico will produce over 24 million metric tons of corn products this year—an increase of nearly 14% over last year) [1] reproduce by spores that are spread by natural mechanisms, and enhanced by anthropogenic activities. In 2008, the top vegetable exports from Mexico to the United States included tomatoes, peppers, onions, and fruits—all susceptible to common and adapting pathogens and parasites. In other countries, viroids (single-stranded RNA viruses without a protein shell) responsible for tomato decline have been inadvertently imported on ornamental plants and other asymptomatic food plant products [2]. There is no fence that can protect against all of these agricultural threats—even if the deliberate movements of all agricultural are stopped.

Of potentially greater concern is the movement of animal pathogens. The most contagious disease of food production animals is Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD). FMD is caused by a virus (FMDv) that affects nearly all cloven-hoofed animals (Figure 2). FMD is of particular concern to the cattle and swine industries. However, this disease also affects sheep, goats, deer and other animals. Animals can become infected with FMDv after exposure to contaminated facilities, vehicles, humans (FMDv does not cause disease in humans), feed, water, or wild animals that may carry the virus but do not become sick from it. A single case of FMD in a country is likely to have significant economic impact because of the international trade bans that will immediately close export markets. The United States has been free of FMD since 1929 [3]. The rest of North America (Mexico and Canada) is currently FMD-free as well. However, FMDv is endemic in many parts of the world and is still a significant concern to animal-exporting countries.

An FMD outbreak started in Mexico in 1946 after infected cattle were imported from Brazil. Once the outbreak had been diagnosed, an immediate ban was put in place to prevent the importation (to the U.S.) of all cloven-hoofed animals from Mexico. The coordination (between countries) of the eradication effort was laborious and time-consuming and the outbreak expanded to an area of nearly 260,000 square miles. It wasn’t until September, 1952—nearly six years later—that Mexico was declared “FMD free” and the U.S. embargo was lifted. The extended value of the coordination efforts between the two countries was illustrated during a subsequent outbreak of FMD in Mexico that began in May, 1953. This time, it took less than a year for the outbreak to end and trade to be re-established [4]. As commerce and traffic increase across the border, the United States and Mexico need to ensure that plans and mechanisms for similar cooperative arrangements are already in place—before another FMD-type outbreak occurs.

On 6 July 2011, the United States and Mexico signed an agreement that will allow trucks from both countries to traverse the other’s highways. This accord provides resolution to a dispute over part of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The U.S. Department of Transportation states that safety concerns related to the operation of Mexican trucks on U.S. highways have been resolved [5]. Unfortunately, the resolution of operational safety concerns does not mean that there is no additional threat to agricultural health from the bi-direction flow of commercial vehicles across the U.S./Mexican border.

As a further example of this real threat, while there are some unresolved scientific issues, the cause of the 2007 FMD outbreak in the United Kingdom (Figure 3) has generally been attributed to the inadvertent transfer of FMDv by in mud on a truck tire. According to the government’s Health and Safety Executive (HSE) report [6]:

“We established that some of the vehicles, probably contaminated, drove from the site along a road that passes the first infected farm. We conclude therefore that this combination of events is the likely link between the release of the live virus from Pirbright and the first outbreak of FMD.”

Thus, there should be some concern that more liberal access for trucks (American and Mexican) could enhance the potential for the spread of FMD and other agricultural/animal diseases with undetected rapidity. A clear understanding of sanitary animal shipping practices and methods of inspection and verification must be in place to help minimize the potential for the enhancement of disease spread if an outbreak was to occur.

Additionally, there are human health issues that are potentially exacerbated by the deteriorating conditions along the U.S./Mexico border. Many Mexican and American nationals along the Texas/Mexico border live in colonias—small and usually impoverished communities. It is estimated that there are 2,300 colonias in Texas [7]; it is difficult to enumerate the colonias on the Mexican side of the border. The U.S. government and the State of Texas have committed the talents of many individuals and agencies to address human health issues in the colonias; significant resources have been invested to improve the conditions for the colonia residents and much progress has been made. However, the evolving issues in the border area will potentially add to the public health problems that plague these residents and may provide a border-area “foothold” for larger public health crises.

In Texas, nearly 45,000 people live in 350 colonias classified as “highest health risk.” These colonias are lacking potable water and/or wastewater disposal systems and/or solid waste disposal systems, etc. [8]. The inhabitants of such colonias are already suffering from higher than normal rates of water-borne and vector-borne (i.e., mosquito) diseases. Accommodating additional persons (either transient or permanent residents, who may also bring new disease concerns) will likely apply an additional burden to the existing public health infrastructure and increase the potential for localized disease outbreaks. A growing number of Mexican nationals are leaving Mexican border areas (like Ciudad Juarez) to seek a more peaceful, but perhaps more impoverished, lifestyle in the U.S. [9]. Meanwhile, non-governmental agencies that have historically provided assistance and support to the inhabitants of the border have become less active because of the threats of border violence. An increase in the morbidity of easily treatable bacterial diseases and other vaccine preventable diseases should be expected.

An unfortunate and continuing illustration of this concept is taking place in Haiti. Parts of Haiti were devastated by a magnitude 7.0 earthquake that struck near the capital of Port-au-Prince on January 12th, 2010. The international response to the Haiti disaster was swift—governmental and non-governmental agencies rushed to provide relief to the victims. Unfortunately, in October 2010, the beginning of a Cholera outbreak, certainly enhanced by the lack of infrastructure and sanitary conditions resulting from the earthquake, was identified. Cholera is a bacterial disease (causative agent Vibrio cholerae) that can generally be avoided if clean water is available and the disease is easily treated (with a high success rate) by using a combination of hydration and antibiotic therapies. Documented cases of Cholera had not been reported in Haiti for decades. Even with significant levels of international assistance, over 360,000 people were sickened in Haiti by Cholera and more than 5,500 died of the disease—as of the end of June, 2011 [10]. An ironic twist came from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in a July, 2011, report. The CDC report states the evidence “strongly suggests” that the source of the Cholera outbreak was a United Nations camp—housing Nepalese peacekeepers. This illustration is presented to make two points:

1) Even when response personnel and logistics are available to address the needs of a growing population without adequate infrastructure, human health issues can be overwhelming;

2) An all-hazards risk assessment should have identified the potential for unanticipated introduction of disease to a vulnerable population and been used to inform the relief coordination efforts.

While gun violence, kidnapping for ransom, human trafficking, and other “high profile” incidents capture much of the public and media attention, with respect to border issues, other hazards (agricultural and public health threats) also continue to pose significant, and escalating, risks. It is imperative that when both countries invest in solutions for the current crises that these hazards are considered alongside the attention-grabbing violent events with which we have become so familiar.

The Plan

Consistent with the perspective engendered by the quotation of Warren Buffett, we must identify all of the hazards and assess them to appropriately address the risks. In common vernacular, risk is something that causes injury or loss. In this sense, risk is often subjectively assessed on personal experiences and expertise or the perceived level of personal (or family) peril. In technical terms, risks are commonly defined as the product of the likelihood of an unfavorable outcome and the consequences of that outcome. That is, the level of risk depends on how frequently a negative situation is expected and how bad the situation gets. An objective and systematic review of the likelihood and consequences of all hazards is the basis for a any useful risk assessment.

Images and imagined catastrophic situations can artificially (high) bias the perception of risk because these catastrophic situations may be very damaging in terms of health, finances, liberties, etc., however infrequent. Other hazards may be inappropriately perceived as low risk if the consequences are less damaging but occur more frequently or are more likely to occur. It is suggested that using a systematic approach to an all-hazards border risk assessment can help differentiate the real risks from the perceived risk—removing subjective biases and subsequently informing the decision-making authorities about the best use of collective resources for the most effective mitigation measures.

A systematic approach would include multiple steps and would be repeated periodically as new hazards are identified, as additional data fidelity is available, or as underlying circumstances change the assumptions and likelihood of events. The steps may include, but are not limited to:

1) Identifying hazards and threats to public health & safety, business and economic stability, infrastructure, and national defense;

2) Development of event sequences (and semi-quantitative estimates of the probability of each step in the sequence) that represent scenarios leading up to an event with an unfavorable outcome;

3) Developing and using models that will estimate the consequences of each scenario in some common and measurable term—typically expressed as economic consequences—even for illnesses (loss of productivity) or death (loss of life);

4) Ranking of hazards and threats by an established risk (probability x consequence) metric;

5) Testing the effectiveness of hypothetical hazard and threat mitigation costs to reduce the estimated consequences; and

6) Providing recommendations on the tactical and strategic use of resources to address the assessed hazards and threats.

Using a systematic approach should, theoretically, result in the maximum risk mitigation (benefit) for any fixed allocation of resources (money) that a state (like Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, or California) or federal government (Mexico, United States) has available. It is already evident that using a haphazard approach to inform resource investment decisions for solutions to perceived or misperceived border problems may lead to counterproductive outcomes, including wasteful spending and even new threats. For example, The United States Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) has disclosed [11] that a an operation designed to help mitigate threats from trans-border weapons traffickers (Operation Fast and Furious) has resulted in more small arms being delivered to organized crime cartels in Mexico. ATF Special Agents and support staff are outstanding public servants and are committed to their profession and roles in border security. However, it is postulated that the resources used to cover the cost of this operation and all of the subsequent investigations could have been put to better use if an all-hazards awareness perspective and risk assessment process were used. Without a complete and systematic assessment of all related hazards and threats, however, it is difficult to determine if similar operations (i.e., risk mitigation techniques) directed against arms trafficking provide more benefit than risk mitigation techniques designed for other hazards—like agricultural and public health concerns.

Summary

The increasing instability of the U.S./Mexico border area is a local, state, regional, national and international concern that affects public health, agricultural (plant and animal) health, public safety (rising levels of violence), and regional and national economies. A collaborative, all-hazards/risks assessment approach should be employed to objectively address these risks in order to understand the consequences of each type of hazard and the likelihood (or frequency) of significant high-consequence events. Addressing individual threats/hazards without having an associated governing strategy provided by a systematic approach to risk assessment will often lead to the ineffective use of resources and/or unintended outcomes, which in turn may lead to additional unanticipated risks. Until both countries (and states) join in a collaborative effort to periodically assess the full spectrum of hazards and threats, it will be increasingly difficult to distinguish perceived threats from those that are potentially catastrophic to one or both nations. Consequently, our resources may be misapplied by providing solutions (or attempted solutions) to problems that have minimal impact.

Many collaborative efforts have successfully demonstrated the benefit of international and interstate cooperation. The United States—Mexico Border Health Commission (BHC), with its mission to optimize health and quality of life along the border, has identified many worthwhile strategic priorities and has plans to support additional conferences, forums, summits, and projects in the future [12]. The BHC mission, being focused on human health issues, could provide useful input to an all-hazards threat assessment and risk assessment. The Texas Animal Health Commission and the Texas Department of State Health Services are also well positioned to contribute to an all-hazards assessment, but state budget have made it difficult for these agencies to advance such initiatives. (The “across the board” Texas budget cuts are another example of a solution that may have benefited from a broader assessment of all hazards risk assessment and consequences analysis.) Other state agencies (in Texas and other border states on both sides of the border) could also provide useful input to a high-level, all-threat border risk assessment. However, there is apparently no functional organization with such a mission.

Solutions to these problems may be suggested from policy-level recommendations and analysis provided by a newly formed committee of border state representatives: a Texas—México border committee on all-threats mitigation and response planning. Such a committee would comprise leaders from academia, industry, and government with expertise in organized crime, agricultural diseases (animal and plant), human health, immigration, drug trafficking, economics, human trafficking, and other pressing border issues. These leaders would be supported by risk assessment professionals using a systematic, evidence-based approach to quantitatively (or at least semi-quantitatively) identifying mitigation and response strategies that provide the broadest and most beneficial benefits from the use of our limited resources. Of course, the political support and funding needed to initiate such an effort becomes part of the overall conundrum. Perhaps this is an issue that may be best addressed by a “grass-roots” initiative to coordinate the use of resources provided by civic organizations in the affected border states.

References

[1] United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), ‘Mexico Corn Production by Year,’ retrieved 13 July 2011,

http://www.indexmundi.com/agriculture/?country=mx&commodity=corn&graph=production

[2] Matthews-Berry, S., The Food and Environment Research Agency, “Emerging viroid threats to UK tomato production,” July 2010, Crown copyright.

[3] USDA, “Foot-and-Mouth Disease,” Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) Factsheet, Veterinary Services, February 2007.

[4] USDA, Agricultural Research Service, “History of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Outbreaks in North America,” May 1969, retrieved 13 July 2011,

http://members.bellatlantic.net/~vze4hqhe/history/fmdars.htm

[5] Katz, Jonathan M., Associated Press, “US agrees to let Mexican trucking in all states,” updated 6 July 2011, retrieved 13 July 2011,

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/cleanprint/CleanPrintProxy.aspx?unique=1311183027054

[6] Health and Safety Executive, Final report on potential breaches of biosecurity at the Pirbright site 2007, September 2007.

[7] Ramshaw, Emily, “Red Tape, Catch-22s Impede Progress in Texas’ Colonias,” The Texas Tribune, 8 July 2011, retrieved 13 July 2011,

http://www.texastribune.org/texas-mexico-border-news/texas-mexico-border/red-tape-catch-22s-impede-progress-texas-colonias/

[8] U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, “CHIPS: Monitoring Colonias Along the United States-Mexico Border in Texas,”

USGS Fact Sheet 2008-3079, September 2008.

[9] Giovine, Patricia, Reuters, “More Mexicans fleeing the drug war seek U.S. asylum,” 19 July 2011, retrieved 20 July 2011,

http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/07/19/us-usa-mexico-asylum-idUSTRE76I6P020110719.

[10] Associated Press, “Haiti cholera outbreak blamed on UN force,” 30 June 2011, retrieved 22 July 2011,

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/jun/30/haiti-cholera-outbreak-un-force .

[11] FoxNews, “ATF Chief Admits Mistakes in ‘Fast and Furious,’ Accuses Holder Aides of Stonewalling Congress,” 18 July 2011, retrieved 20 July 2011,

http://www.foxnews.com/world/2011/07/18/atf-chief-admits-mistakes-in-fast-and-furious-accuses-holder-stonewalling.

[12] United States – México Border Health Commission, “BHC Initiatives,” January 2011, retrieved 1 August 2011,

http://www.borderhealth.org/bhc_initiatives.php

Jerry Lara / San Antonio Express-News

Jerry Lara / San Antonio Express-News