Vertical gardening, memory, and place-making in Palestine

By Lama Ab Shama

Introduction

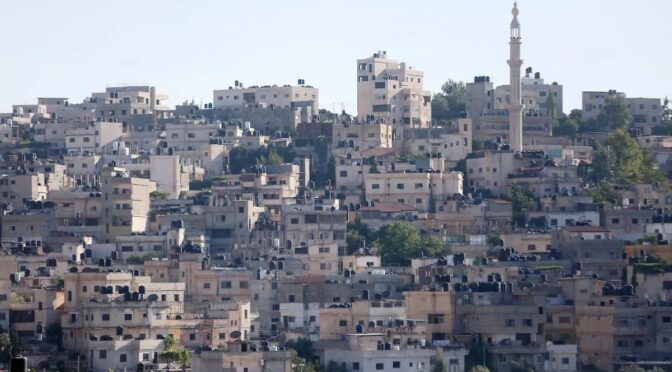

Jalazone Refugee Camp in the Ramallah and al-Bireh Governorate is one of 19 official and four unofficial Palestinian refugee camps in West Bank, Palestine. It was established in 1949 on almost 253,000m² land after the 1948 Israeli war that expelled Palestinians from 36 villages, most located in central Palestine. According to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), in 2015, the camp accommodated nearly 11,000 refugees. The camp suffers from overcrowding problems, inadequate infrastructure, and a shortage of available land for building or expansion. While Palestinians who live in the camp have been there for more than seven decades now, many refuse to leave it because they view it as a temporary condition and a symbolic representation of their right to return to their homes before the war.

Acknowledging both the longevity of life in the camp and its temporary nature, Swedish artist Sara Gebran collaborated with students at Birzeit University in the West Bank in 2010 on a project called The Vertical Gardens, which aimed at creating green spaces in the camp, but vertically. Historically, Palestinians have strong spiritual, emotional, and physical connections to land and plants, especially older women who used to sing and talk to their plants like their children The goal of the project was to plant on walls, roofs, windows, and other vertical spaces using materials found in the camp, including recycled tires, empty plastic pots, and bottles, to increase the green cover and make the environment more pleasant and livable.

Analysis

Palestinians in Jalazone Camp dream of returning to their lands and homes, but they have been in the camp for so long that their “place attachment” to their original home may not be that strong. At the same time, making a connection to a place they consider temporary is also challenging. When the team introduced the project to the camp residents, they were concerned that residents’ might feel the project would represent a rejection of their right to return. In using plants, the project aimed at enhancing the living conditions in the camp without compromising refugees’ right to return while simultaneously connecting to their original home through their relationship with plants.

Despite the difficult material conditions of the camp and the refugees’ struggles in this temporary location, my fellow students and I noticed that residents felt an attachment to the place when we started the project. As Friedmann suggests, such place attachments can be “subjective and invisible under normal circumstances” (Friedmann, 2010, p. 155), but suddenly they may become visible when external interventions take place. This happened when we went to the camp to initiate the project: the residents responded enthusiastically and decided to join us to improve their environment, despite the temporary nature of the camp. Their engagement with the project derived from their strong sense of place, which can be understood as the bonding between a person and the environment (Shamsuddin and Ujang, 2008).

We focused the planting in the main locations where people gather, including a youth center called Al Karameh Center, a mosque, and a local café, which allowed us to foster interactions between camp residents. We also decided to add green decorative elements to the windows and facades of the buildings and create a roof garden on the top of the Al Karameh Center using portable and flexible containers. By focusing on places where people interact with each other in the camp, we pursued what Friedmann (2010) refers to as “the centering of place” to constitute place through social practice.

In the camp, elderly refugees have memories of their childhood in their original home before the war. In the project, it was essential to enhance spaces in ways that would help create memories for the young generations who were born in the camp. We did this by fostering social interactions and events that enhanced the emotional relationship between the individuals and their surroundings (Shamsuddin and Ujang, 2008) while also respecting the history and symbolism the camp holds.

Implications

Given the symbolic significance of the Jalazone as a temporary settlement, understanding the camp community and its historical background, the relationship between plants and people, and how emotional connections emerge from such interactions became crucial for the project. It was also vital to encourage participation by different age groups and residents of various backgrounds to draw on diverse experiences and knowledge. This bottom-up approach strengthened attachment to place and provided a collective sense of belonging and identity. In the long term, the small vertical gardens that were created on spaces such as windows, rooftops, and walls could also possibly provide an opportunity for economic development for Palestinians in the camp. The project thus brings various opportunities to the camp community while respecting the residents’ desire to return to their homes before the war.

The old ladies who participated in the project had happy memories of their original homes and lands where they used to plant trees, vegetables, and fruits. I believe that their nostalgia for their original homes spurred their engagement in this project. This further illustrates the power of memory and how it acted as a vital source for community-based planning. “Such affective landscapes bring together embodied, sensorial, and more-than-human fields of action to shape everyday politics in which residents narrate their marginalization within the world city and articulate their own value here.” (Gupta, 2020, p. 1688). The project reinforced a sense of community derived from shared feelings of belonging to a group and emotional connection based on a shared history, thus generating place attachment, which motivated people to improve their place under challenging circumstances. In so doing, the project transforms a “space” into a “place” by acquiring deep meaning through the “steady accretion of sentiment” and experience (Friedmann, 2010, p 156). As Shamsuddin and Ujang (2008, p 400) suggest, since the place is “an experiential process, it is important to examine the meanings that people attach to a locality in trying to create a sense of place.”

Palestinian Refugee Camp, Ramallah, West Bank. Source

Group meeting of the Swedish artist with Birzeit University students and Jalazoune Camp residents. Source: Photo taken by Lama Ab Shama.

Decorative elements. Source: Photo taken by Lama Ab Shama.

Planting pots. Source: Photo taken by Lama Ab Shama.