Long-standing community practices can guide more ethical and grounded participatory planning

By HyukJoon Kwon

Introduction

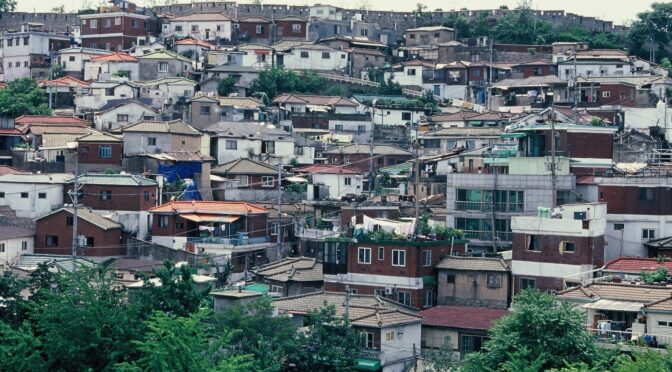

Jangsu Village, located in Seongbuk-gu near the historic Hanyangdoseong (Seoul City Wall), is a hillside settlement established in the 1950s by post-war refugees. Eventually encompassed by Seoul’s rapid expansion, the residents historically relied on manual labor and nearby textile industries to sustain a tight-knit community based on mutual support. Despite this strong social fabric, the neighborhood—inhabited primarily by low-income and elderly residents—suffered for decades from deteriorated housing, lack of basic infrastructure, and severe development restrictions due to its designation as a Cultural Heritage Protection zone. These conditions left residents in a precarious situation: although the area was labeled a “slum” and targeted for large-scale redevelopment in 2004, the project stagnated due to low profitability, leaving residents in limbo and vulnerable to displacement.

During this period of uncertainty, a different model of intervention emerged. Formalized by the Seoul Government in 2012, the city adopted a resident-led urban regeneration model. Residents, activists, and officials collaborated to improve housing conditions and safety while preserving cultural identity through participatory methods. Regarding the village’s visual identity, it is important to note that the colorful murals were not an ancient tradition, but a recent artistic intervention introduced during this process to improve the living environment. The intervention emphasized incremental upgrades—such as housing repair subsidies and the creation of the Village Museum—while avoiding displacement and prioritizing the everyday needs of residents.

Analysis

Rather than approaching the neighborhood through technocratic redevelopment, the regeneration of Jangsu Village centers residents’ lived experience, everyday practices, and cultural memory—elements that critical planning scholars highlight as fundamental to just and context-sensitive urban transformation. This reflects regeneration as a process rooted not only in spatial intervention, but in meaning, attachment, and memory infrastructures embedded in place.

Friedmann (2010) argues that meaningful place-making emerges from situated practices and residents’ intimate relationships with their environments. Similarly, Shamsuddin and Ujang (2008) emphasize how emotional bonds and long-term social ties shape community action. In Jangsu Village, long-term residents’ deep attachment to the hillside settlement motivated their resistance to displacement and informed the desire to preserve its spatial identity. This attachment became a political force: it guided priorities such as incremental housing repair, maintaining the existing street fabric, and ensuring that improvements strengthened—rather than replaced—community life. Here, place operates not only as physical environment but also as a repository of memory and lived narratives, forming the foundation upon which regeneration could emerge.

The case also reflects broader theories of everyday urbanism. Hernández (2019) highlights how small-scale, daily practices constitute powerful forms of agency, especially in marginalized neighborhoods. Jangsu Village illustrates this dynamic clearly through the residents’ active use of interstitial spaces. Specifically, residents transformed narrow alleyways into communal living rooms, gathering on wooden benches to share food and tending to doorstep gardens. These practices evolved into broader collective actions: collaborative mural painting projects drew external visitors and reshaped the village’s public image, while resident-led workshops—such as the ‘Village Carpenter’ and community craft initiatives—produced local goods and services that promoted the neighborhood’s unique identity to the outside world. These everyday practices built social cohesion and established the organizational capacity necessary for later planning processes.

The case of Jangsu Village also resonates strongly with Miraftab’s (2009) framework of insurgent planning. Miraftab distinguishes between “invented” spaces created by marginalized groups and “invited” spaces structured by the state. In Jangsu Village, residents and local activists had already created invented spaces of action—community schools, cooperative workspaces, and self-organized neighborhood initiatives. When the Seoul Metropolitan Government initiated the regeneration project, these grassroots practices were incorporated into invited spaces, effectively transforming insurgent participation into institutionalized collaboration.

Implications

The case of Jangsu Village demonstrates what planning can accomplish when the field expands beyond technical intervention and engages with the textures of everyday urban life. Jangsu Village is not merely a physical upgrading project but a complex, multi-layered regeneration process rooted in place attachment, everyday practices, hybrid governance, and narrative belonging. It exemplifies a planning model where resident agency shapes urban outcomes and where formal planning evolves through meaningful engagement with informal community life. The community networks that sustained Jangsu Village for years prior to formal intervention complicate the binary between “planned” and “unplanned,” illustrating that cities are continually shaped by ordinary practices that fall outside the framework of formal policy (Hernández, 2019).

At the same time, the case raises important considerations for planners regarding reflexivity and positionality. In Jangsu Village, the involvement of municipal officials, researchers, and planners required continuous negotiation: they needed to support resident leadership without directing it, facilitate participation without speaking on behalf of the community, and remain aware of how their own social and institutional positions shaped interactions. This reflects ongoing calls for planners to approach community-based work through accountability, humility, and relational solidarity (Roy, 2006; Vasudevan, 2022). Ultimately, the case points toward a form of planning that is attentive to social infrastructures, receptive to informal capacities, and responsive to the stories that ground communities in place (Sandercock & Attili, 2014).

Source: Volunteer home-repair services.

Source: The wall was transformed into a vibrant mural village through the hands of the students.

Source: Through the collective making of dolls, residents enacted everyday practices that reinforced local identity and community solidarity, known as ‘grandma doll’.