Art, Performance, and Mobilites in the US-Mexico Borderlands

By Lucy Hall

Introduction

The Mexican-American border has always been a site of violence. Since its creation in the early 19th century, American military forces have brutally policed the movement of people across it in some way. Sometimes it was to force indigenous people out; other times, to keep enslaved people in (Little, 2019). The border wall wasn’t erected until much later in the 1990s, but the air of violence remained. As Anzaldua (2012) suggests, “Borders are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them. A border is a dividing line, a narrow strip along a steep edge. A borderland is a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. It is in a constant state of transition. The prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants.”

However, even before the border wall, there was border art and performance. For decades, people of all origins, professions, and mediums have come together to transform a site of violence into a locus of imagination, subversion, and insurgent citizenship (Miraftab, 2009). They challenge its authority and reimagine ownership.

Analysis

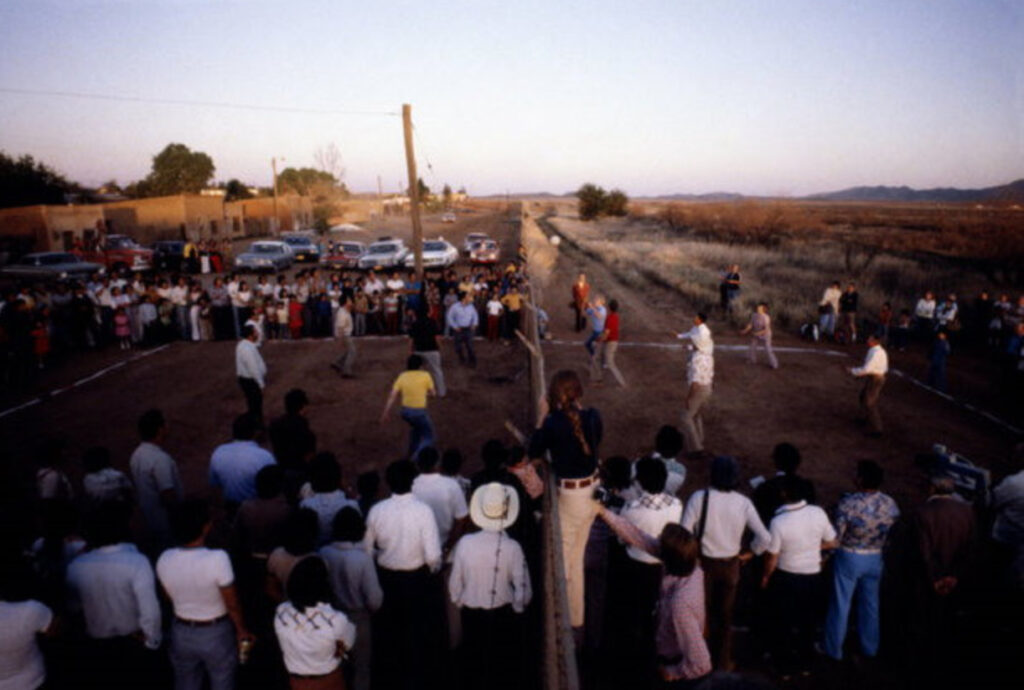

In one such reimagining, called “Re/flecting the Border,” artists organized a communal meal against a large mirror on one side of the border. The mirror acts as an illusion to effectively make the border disappear and suggest an intimate connection with those on the other side. In other imaginings, the border still exists, but its power does not. For example, the yearly walleyball festival in Naco, Arizona and Naco, Sonora merely renders the border a sort of prop. By using the border wall as a walleyball net, they assert dominance over the wall by transforming it from a weapon of state control to a mere element of a sports event. In so doing, the players undermine its authority. The separation that the wall creates is further undercut by the performance of adherence to a “side.” The status of their citizenship is reduced simply to a sports team affiliation.

Organizations have also taken it upon themselves to transform the border in more permanent fashions. Art center Casa del Tunel has been bringing various local organizations, like Dreamers’ Moms, together to paint 10-meter sections of the border wall in Tijuana. These beautification projects simultaneously work to reclaim the wall as a community canvas instead of a structure that criminalizes them and divides them from family.

Implications

As militaristic nation-building efforts have created a violent border region, border art and performance offer opportunities to challenge notions of citizenship through insurgency and movement, undermine the power of state-sanctioned violence through subversion, and imagine new futures through creativity and community. The constant, unsanctioned movement of bodies across the border takes the authority of the state and its notions of citizenship to the task. Hundreds if not thousands cross over every year, and in so doing, redefine their own citizenship through insurgent movement (Miraftab, 2009).

As migrants challenge state authority and state ownership of citizenship through human movement, they also do so through human infrastructure. Coyotes and migrants from expansive human networks that can begin as far south as El Salvador and use multiple modes of transportation and hiding places, generating “a sense of unaccountable movement that [travels] great distances” (Simone, 2004, 428). These migrants and their guides rely on an “infrastructure of people” which “emphasizes economic collaboration” among individuals who operate outside of legality (Simone, 407).

The pathologization of migrant behavior and border spaces serves to justify the continued state-sanctioned violence that occurs on the border. As Kamete (2013a) suggests, expert agents of the state “dominate urban spaces by…defining standards of normality and abnormality” (641). Simply by existing, the border wall defines what is normal, and thus worthy of protection (the U.S.), while simultaneously defining what is abnormal, and thus in need of correction and control (Mexico). When these insurgent creators make use of the border wall to serve their own interests, such as a walleyball net or the canvas for a work of art, they are draining the dominance from both the border and the state that erects it.

For those who live on the Mexican side of the border, imaginative and collaborative, arts-based activities envision a future without a wall. As groups like Casa Del Tunel and Dreamers’ Moms collaborate on wall beautification projects, they “conjure up worlds beyond current conditions” and imagine a new future for themselves (Ong, 2011, 13). Instead of the border being a site of division, it instead becomes a site of communion. They engage in the “very act of reimagining or redesigning” space (Ong, 2011, 4). These communities exemplify the sort of collaborative, cultural activities that allow ordinary people to “constructively build within the wastelands of traditional policy-makers and urban planners” (Mbaye, 2018, 582) and “engage in transformative processes [that integrate them] in the conception and production of arts and culture for the wellbeing of citizens” (Mbaye, 580). The notions of both collaboration and creativity are key here because it is this former that enables them to contest hegemonic institutions and the latter that makes their resistance to larger social structures revolutionary (Prasetyo, 2017).

Even though the border may be extended in the coming years, it is clear that communities on both sides have the capacity to challenge its presence in powerful ways, inviting international planning as a field to reinvent the notion of citizenship, subvert dominance, and imagine new worlds and ways of belonging through community and collaboration.