Place-making and alternative development in Oventic, Chiapas

By Maureen Rendon

Introduction

Upon the ratification of NAFTA in 1994, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), formed primarily by the Indigenous populations of Chiapas, led an uprising against the Mexican government. Two years later, negotiations between the Zapatistas and the Mexican government produced the San Andrés Accords, which granted them Indigenous rights to land. Even though the government failed to comply with the Accords, the Zapatistas today still control 43 autonomous areas, including 12 caracoles and 31 autonomous municipalities (Jung, 2003, p. 447).

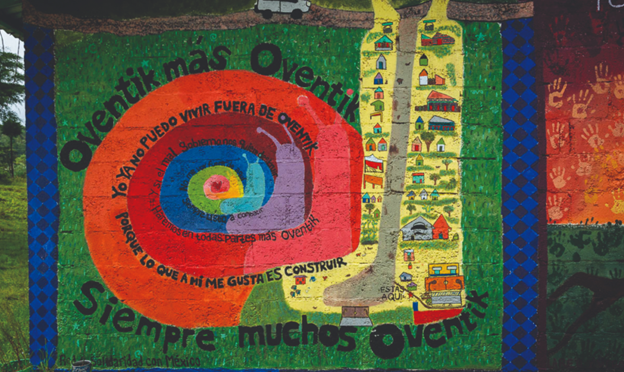

By dividing their territories into five “snails”, or caracoles, the main political units led by juntas de buen gobierno (“councils of good government”), the Zapatistas have been able to maintain political structures that reflect their direct resistance against the Mexican government (Fleming, 2018), including the Zapatistas’ radical place-making through the medium of muralism. The Zapatista murals, which follow the Mesoamerican and Mexican revolutionary tradition of muralism, are vivid and colorful. Common imagery found in their murals includes the traditional maize plant, revolutionary actors such as Che Guevara or Emiliano Zapata, and representations directly connected to nature. This analysis focuses on the mural “Another World is Possible” found in Oventic village in Chiapas (Fig. 1), showing how each of the sentences in the mural illustrate four major themes: alternative development, self-governance, place-making, and insurgent planning.

Photo by Dane Strom. “Another World is Possible.” See source here: Cipher Magazine.

Analysis

The Zapatistas are contributing to conceptualizations of alternative forms of development based on a radical breach with government-based foreign aid and international development approaches. Arturo Escobar (1996) argues that contemporary forms of development arose from a discourse centered on dualisms between Global North/South and developed/underdeveloped countries. These dualisms have reinforced the understanding of histories through Western-based ideologies “that dictates that the Third World and its people exist ‘out there,’ to be known through theories and intervened upon from the outside” (Escobar, 1996, p 8). By understanding the situated knowledge of the Zapatistas, we can recognize alternatives to development while avoiding the danger of homogenizing alternative development across the Global South (Gudynas, 2011). The Zapatista perspective on alternative forms of development is illustrated in the mural in Oventic which shows five snails layered within each other, with the body of the snail representing a road with houses and a community, and which includes the statement, No me voy fuera de aquí. Siempre listo a combatir (“I won’t go from here, always ready to fight”) (Storm, 2018).

In turning towards alternative development and Indigenous knowledge, the Zapatistas have been able to preserve their agency in the face of state-sanctioned violence. Through the caracoles, local representatives are able to prioritize community-based decision-making (Fleming, 2018) and practice self-governance as defined by Nunbogu et al. (2018) as “the freedom with which individuals and communities undertake initiatives and coordinate their actions for accomplishing a set of objectives” (Fleming, 2018; Nunbogu, p. 33). This emphasis on self-governance is illustrated by the mural in Oventic, which shows colorful housing in a consolidated community within the broader scope of the caracol and states, Porque lo que a mi me gusta es construir (“Because for me what I want is to build”) (Storm, 2018). While Western understandings of progress are premised on economic development, technological innovation, and global cities, the Zapatistas center Indigenous experience and knowledge within their systems of governance, including Indigenous-based primary and high school education, coffee cooperatives, and community-based healthcare systems.

The Zapatistas also engage in practices of place-making in order to preserve small places that are “inhabited, and come to be cherished or valued by its resident population for all that it represents or means to them” (Friedmann, 2010, p. 154). Through their autonomous control over municipalities and their consolidated political structures, the Indigenous populations are able to preserve place through their “rootedness and connection to a spatial setting… [and] by interpersonal empathy and social bonding” (Alawadi, 2017, p. 2980). As the mural in Oventic demonstrates, Y si el mal gobierno quiere destruir, haremos en todas partes más Oventik (“And if the bad government wants to destroy us, we’ll make everywhere more Oventik”) (Storm, 2018). This statement illustrates Indigenous conceptions of place-making, as the placing of the snails within each other reflects the situated knowledge that flourishes within the Zapatistas’ Indigenous territories.

Finally, the Zapatistas politicize their actions and community-based planning to directly counteract the harm that has been imposed on Indigenous communities by neoliberal policy. Their approach can be understood as a form of “insurgent planning” through the development of invented spaces for policy-making and visioning of governance alternatives. Through insurgent planning, the Zapatistas of Oventic have been able to “destabilize the normalized order of things… by locating historical memory and transnational consciousness at the heart of their practices” (Miraftab, 2009, 33). As the mural declares, “Oventik, más Oventik. Siempre muchos Oventik” (“Oventik, more Oventik, always lots of Oventiks” ) (Storm, 2018). This statement reflects the need to continue creating invented spaces to increase the resistance against the government, which until today, has failed to grant Indigenous rights to the Indigenous populations of Chiapas.

Author’s mother owns this photo, and it was obtained through personal communication and permission. Photo source: Sandra Madrigal, Chiapas, Mexico.

“The Zapatistas: History and Current Role in Mexico.” See source here: Jane Schwartz.

Implications

The case of Zapatista muralism illustrates the importance for planners of placing Indigenous populations, knowledge, and geographies at the core of their work. By engaging directly with Indigenous communities and acknowledging the heterogeneity of ethnic, religious, and cultural differences across the Global South, planners can understand that alternatives to development cannot be transported from one place to the next (Gudynas, 2011). This case study is also an urgent call for the Mexican government to uphold the San Andrés accords. Establishing a formal relationship between government and citizens will allow for more cooperation and the facilitation of dialogue between parties as it relates to community-building and sustainable development, as called for in the Zapatista mural that states, “Red y solidaridad con México” (“Network and solidarity with Mexico”) (Oventic mural, n.d.).

The Zapatistas also offer a new notion of community building, where Indigenous communities deploy technical knowledge and skills-based approaches to preserve their own history (for example, through murals and access to education based on Indigenous knowledge), build their coffee and agricultural exports, and ensure protection from further displacement. As shown in the Oventic mural, each caracol is painted within another, illustrating the Zapatistas’ multi-layered approach to interconnected community building. We can learn from the Zapatistas that community empowerment can be achieved by centering situated knowledge at the core of the planning process.