A nation’s insurgency and placemaking efforts to take back the city.

By Rand Makarem

Introduction

On October 17, 2019, the streets of Beirut saw a wave of protests following a cabinet announcement of new tax measures. This popular movement gave rise to a revolution against a corrupt political system that has left the country in stagnation and misery for over 35 years (Atallah, 2019). The revolutionary movement manifested most notably through the re-appropriation and unprompted reconfiguration of public spaces, which have long been subject to privatization, gentrification, and demarcation (Lakrouf, 2020). This included the reclamation of downtown streets, spaces and facilities that have been inaccessible for most citizens (Sinno 2021). For instance, Riad el Solh Square and the Ring Intersection became the center stages for protest activities. The abandoned cinema “The Egg” and The Grand Theater of Beirut were reclaimed and used as community centers and performance spaces, and the Samir Kassir Garden and privatized public spaces such as the Zaytouna Bay were reclaimed and used as spaces for dialogue and gathering. Additionally, the city in its entirety became a canvas for muralism and graffiti as a means to recover stolen or forgotten narratives.

Analysis

This uprising was a multi-generational movement in which citizens put their sectarian differences aside in their quest for basic human rights (Bou Aoun, 2020), including the right to public space. Beirut has been inaccessible to most of the population ever since its reconstruction following the 1975 Lebanese Civil War (Tierney, 2019) due to the privileging of capitalist urbanization and private development. However, during the October 17th revolution, Downtown Beirut became a space for large public gatherings, a unifying platform for protests and activist-led marches, a stage for various civil society group meetings, an agora for public political debates and discussions, an open market for street vendors, and a canvas for exploration (Lakrouf, 2020).

The importance of this reclamation of public space lies in its manifestation of everyday urbanism, reflecting the social and spatial relations that marginalized citizens use to reclaim their city (Hillbrandt, 2017). As highlighted by Watson (2003) and Simone (2004), these counterhegemonic practices have transformative powers. The transitory activities of individuals in Beirut can be understood as tactics (De Certeau 1984) to reclaim public space, revealing the potential of ordinary spaces and informal encounters to facilitate the agency of citizens (Hehl, 2012). Nunbogu et al. (2018) provide an example of De Certeau’s (1984) notion of tactics by showing how transformative, community-based place making and governance allow citizens to link their political and social aims to claim their right to the city.

Implications

The re-appropriation of public space in Beirut exemplifies the collective intelligence of citizens to ‘rebirth’ their right to the city. Public space became integral to the revolution as protestors reclaimed privatized public spaces and reshaped them by transforming them into platforms of expression, debate, and performance. This determination to reclaim public space in Beirut illustrates the challenges faced by Global South citizens when it comes to meaningfully participating in urban governance, demonstrating the need for a radical approach to planning (Friedmann 1973; Sandercock 1998).

Miraftab (2009) views this radical place-making as a manifestation of insurgent planning practices that tend to be transgressive, counter-hegemonic, and imaginative. Through their demonstrations, protestors transgressed the frontiers of the privatized city center and defied the hegemony of the state. By putting on performances in the neglected and closed theatrical spaces of Downtown Beirut and by translating their emotions onto murals, they demonstrated that an alternative approach to public life is possible in Beirut.

Simone (2004) highlights the importance of understanding people’s mobile activities in the city due to the implications such mobile forms of presentations and place-makings have at different sites and different times. The “flexible, mobile, and provisional intersection” (Simone 2004: 407) of protestors’ movements is indicative of how they produce and reproduce their city. In a similar vein, Prasetyo (2017) and Castillo (2016) introduce case studies from Bandung, Indonesia and Guangzhou, China, to demonstrate how the mobilities of people are intrinsic to place-making. Once individuals decide to bring about change in their city, they develop structures of solidarity and support to guide their placemaking movements within the city.

The October 17th uprisings in Beirut were successful because for the first time in 35 years, citizens realized that they were never truly considered as decision making participants in the country’s neoliberal governance. Thus, the case of Beirut invites planners to understand that planning is not done just by planners (Miraftab, 2009) and to recognize the power associated with innovative, oppositional practices.

The Map: Beirut’s Demonstrations as Live City-Making. 1.Riad el Solh Square. 2. The Egg Cinema. 3. The Grand Theater. 4. Samir Kassir Garden. See Source Here. The map designed by Antoine Atallah shows how different groups of protesters occupied the space to conduct different kinds of activities.

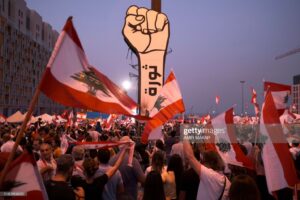

A revolution is born. Protesters wave Lebanese national flags near a giant sign of a fist with the slogan “revolution” on it in Arabic in Martyrs’ Square, Beirut. See Source here.

The roof of ‘The Egg’. See Source Here: Dounia Raphael.

“We want bread, education and joy”. Monà Hallab inside the abandoned Opera House of the Grand Theater in downtown Beirut. See Source Here: Marie-Rose Osta.

Coffee and Politics: A space for dialogue. See Source Here: Annahar Newspaper.