Placemaking through participatory photography and community agency in Bangladesh.

By Farzana Ahmed

Introduction

In a rapidly urbanizing megacity like Dhaka, where informal settlements are often depicted as sites of deprivation, disorder, and crisis, it is rare to encounter initiatives that reposition these neighborhoods as spaces of creativity and collective agency. The exhibition “আমাদের চোখে আমাদের বসতি” (translated as “Our Settlement Through Our Eyes”) represents such an intervention. Held at the Jaago School premises in Korail, one of Dhaka’s largest informal settlements, the exhibition was inaugurated by Dhaka North City Corporation’s administrator, Mohammad Azaz. The exhibit was the culmination of an arts program for residents of Korail that was jointly organized by Korail residents, Nogor Abad, Platform of Community Action and Architecture (POCAA), River and Delta Research Centre (RDRC), JAAGO Foundation, Angeena, and Kula Applied Research Institute.

The arts program taught several Korail residents, mostly women and young people, how to use cameras and other creative tools to record their daily lives, homes, and dreams for the future. Their photos, along with personal stories, were shown to the public to prompt people to think about urban inequality and resilience. The project was part of a larger global movement toward community-led documentation and participatory urban practices that challenge the usual, top-down stories about the informal city.

Analysis

Dhaka’s informal settlements have historically been framed through a technocratic and deficit-based lens. As Roy (2005) argues, the “urban poor” in postcolonial contexts are often rendered visible only as subjects of control and invisibility within dominant planning discourse. In contrast, “আমাদের চোখেআমাদের বসতি” offers a counter-narrative grounded in the epistemologies of those who inhabit these spaces. By handing cameras to residents, the exhibition operationalizes participatory photography (Photovoice) as a methodology of empowerment. The Korail residents thus become knowledge producers, transforming their experiences into visual data that challenges stereotypes about slum life.

The exhibition exemplifies what Escobar (2008) and Ortiz (2022) characterize as decolonial storytelling, an epistemic transformation through the decolonization of urban representation that affirms the right to narrate urban existence from the periphery. The title, “Our Settlement Through Our Eyes,” emphasizes collective authorship and pushes back against the outside gaze of academics, journalists, and policymakers. This project breaks the coloniality of seeing by giving residents more power to represent themselves, which is different from many NGO-driven projects that tell savior stories. It doesn’t use the “poverty explicit” style that is common in mainstream media. Instead, it focuses on happiness, hope, solidarity, and closeness to nature. The project adheres to Watson’s (2009) advocacy for recognizing diverse knowledges and informal rationalities as valid expressions of urban practice.

The participatory process involved in developing the exhibition means it goes beyond merely a display of images. Instead, the exhibition creates an image of Korail as a living, relational environment instead of a messy sprawl by documenting places where people play, work, and relate to each other. These pictures are a way for the community to remember and feel like they belong. As Shamsuddin et al. (2008) and Hernandez (2019) argue, the images show that emotional attachment and a sense of place are very important to community planning. The photographers’ perspectives illustrate how residents’ spatial practices in informal housing enhancements, communal courtyards, and micro-enterprises embody everyday urbanism. These types of spatial production, even though they are not always recognized by formal planning, are examples of adaptive strategies and social resilience that keep city life going even when things are tough.

The involvement of various stakeholders in the exhibit, including municipal authorities, community-based NGOs, and research institutions, illustrates a multi-scalar co-production process (Siame, 2017). When outside interests take preference over community needs, NGOs can co-opt participatory planning to serve the interests of external development instead of community needs (Fateh, 2022). In this case, though, the curatorial structure shows that partner organizations are there to help, not to give orders, which lets residents keep control of their own stories. The fact that the exhibition is in a public space in Korail instead of an exclusive gallery makes it even more accessible and community-owned. This choice changes the event from an art show into a political act of reclaiming space, where people invite outsiders into their homes on their own terms.

Implications

The “আমাদের চোখে আমাদের বসতি” initiative has many implications for urban planning, social research, and decolonial practice. Visual storytelling serves as a democratic tool that reinstates residents’ agency in shaping urban narratives.Urban planners have much to learn from such participatory visual methods, as they allow them to base their research and plan-making on community knowledge rather than on externally imposed frameworks. Exhibitions like this can connect the voices of the community with the city’s government, which can lead to more inclusive urban policies. The project also demonstrates how epistemic justice can be promoted by recognizing the aesthetic and emotional aspects of informal life and the validity of alternative ways of knowing and seeing. The difficulty is in turning this change in how things are represented into lasting change in institutions, making sure that visual empowerment leads to real change.

Ultimately, আমাদের চোখে আমাদের বসতি” serves as a symbol of participatory urbanism and decolonial representation in modern Dhaka. By prioritizing the lived experiences and creative abilities of Korail inhabitants, it challenges established hierarchies of competence and visibility that have historically shaped urban discourse in South Asia. The exhibition not only uncovers alternate perspectives of the city but also redefines who possesses the authority to describe, document, and envision it. In doing so, the exhibition presents a methodological framework for planners, academics, and communities, grounded in empathy, collaboration, and the mundane politics of visibility.

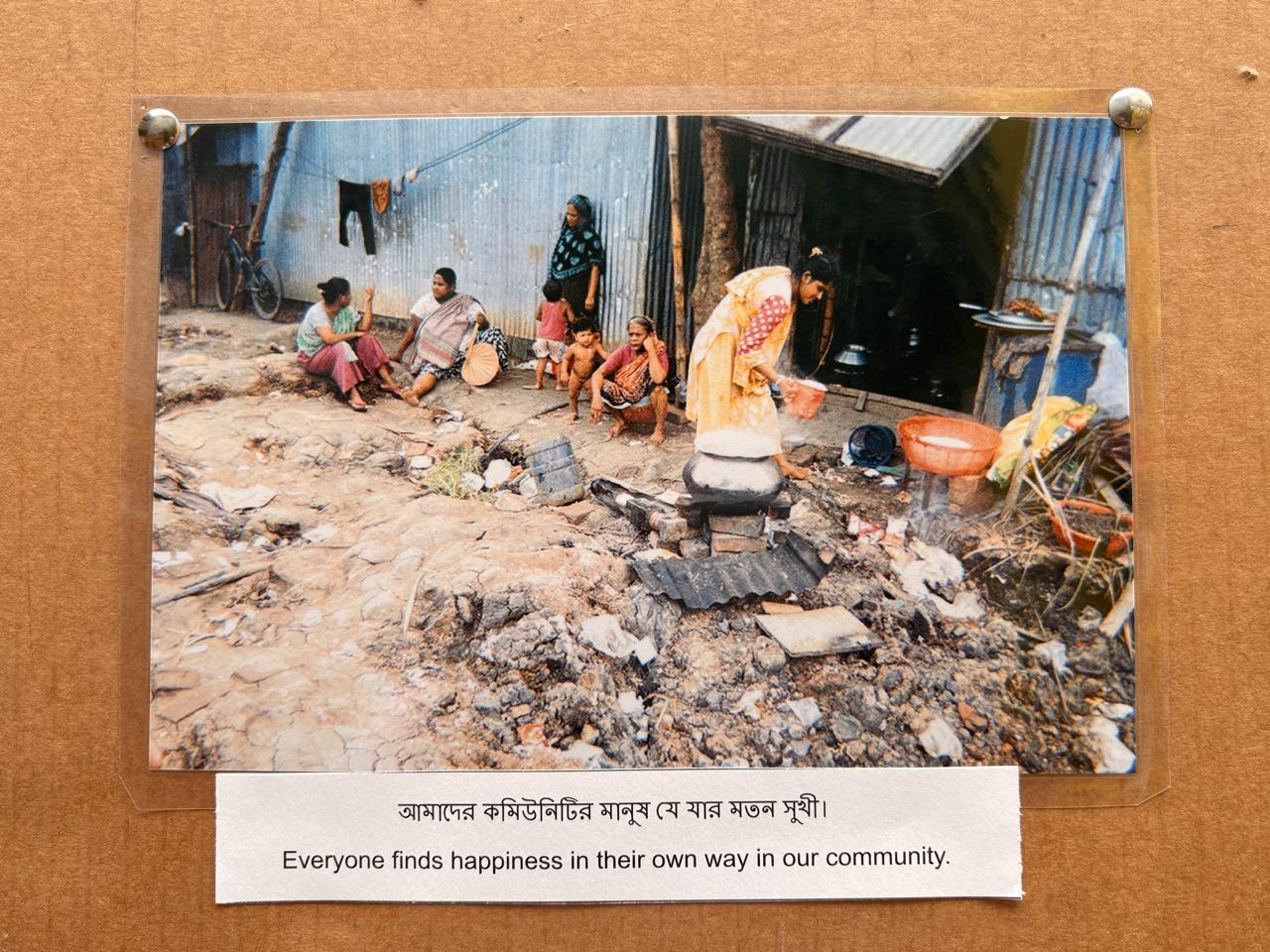

Source: A community kitchen space where women in the community gather to cook, socialize, and care for their children. A community member took this photo

Source: City officials are talking with community members

Source: Exhibition area maintained and decorated by community members