How Singapore’s hawker centers reveal the tensions between heritage, modernization, and state-led planning in a global city

By Sirikitiya Naranun

Introduction

Singapore, a small island nation in Southeast Asia, has long been known for its rapid urban development and strong state-led planning system. Since gaining independence in 1965, the government has pursued modernization through a highly centralized approach, emphasizing efficiency, cleanliness, and economic growth. Within this broader vision, the everyday spaces of the city—markets, housing estates, and food centers—have been carefully shaped to reflect national ideals of order and multicultural identity.

Hawker centers are one of the most distinctive outcomes of this process. Originally, street food vendors operated informally across Singapore’s neighborhoods, providing affordable meals and social interaction for working-class communities. However, by the 1960s, concerns about hygiene, congestion, and the city’s image prompted the government to formalize this activity. Under the direction of the Ministry of the Environment and later the National Environment Agency (NEA), thousands of hawkers were relocated from the streets into purpose-built, covered food centers strategically placed near Housing and Development Board (HDB) estates and transit nodes. By regulating informal vendors, the state sought to modernize public life while maintaining a sense of cultural continuity. Today, hawker centers represent the complex intersection of planning, culture, and governance—spaces where state regulation, everyday practices, and heritage converge.

Analysis

The transformation of Singapore’s hawker centers from informal street food stalls into internationally recognized heritage sites reflects what Ong (2011) describes as “worlding.” This term refers to the way cities position themselves within global networks by selectively showcasing aspects of their culture. In Singapore, this process has reshaped the meaning of hawker culture. What began as an everyday, working-class practice grounded in necessity has been reframed as a carefully curated symbol of national identity and cosmopolitan pride. When UNESCO recognized “Hawker Culture in Singapore” as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2020, the city succeeded in projecting a local practice onto the global stage. Yet, as Ong argues, such global recognition often depends on translating complex local realities into simplified and marketable narratives.

In the case of hawker centers, this translation has produced both celebration and constraint. While NEA regulations sustain the city’s reputation for cleanliness and order they also expose the limits of formalizing everyday culture. Rising operational costs, declining participation among younger generations, and the pressure to conform to standardized practices threaten the spontaneity that once defined hawker culture. As Novoa (2017) suggests, heritage becomes both a recognition of the past and a mechanism of control that shapes how authenticity is performed and experienced.

This tension connects with critiques raised by planning theorists such as Friedmann (1987), who questioned the dominance of top-down modernization and its exclusion of everyday actors. Although hawker centers are often celebrated as inclusive and multicultural public spaces, their evolution reveals how the state uses culture as a planning strategy to project Singapore as both authentic and globally sophisticated. The social and financial costs of sustaining this image, however, are disproportionately carried by small vendors and communities whose informal practices are now tightly regulated. This aligns with Ong’s (2011) observation that Asian cities often achieve global recognition by reworking traditional forms to fit contemporary economic and political agendas. Singapore’s hawker centers are presented as living heritage that connects people to their past, yet they function within a highly structured environment that prioritizes efficiency and global appeal.

Implications

The case of Singapore’s hawker centers reveals that planning is not only about spatial organization but also about the governance of culture and everyday life. The formalization of street life through regulation and branding shows how easily culture can be controlled or sanitized in the pursuit of global prestige. In this sense, hawker centers are not only spaces for eating but also spaces for negotiating the balance between authenticity, regulation, and globalization. The challenge for planners lies in finding ways to support such living culture without freezing it into a static representation. Other cities can learn from this tension. Instead of copying Singapore’s technocratic approach, planners elsewhere might draw from its ability to recognize the social value of ordinary practices while remaining critical of the state’s power to define what counts as “heritage.”

Too often, planning in Western cities treats informality as a “pathology” (Kamete, 2013) to be solved or heritage as a static symbol of the past (Novoa, 2017). In Singapore, informality was not erased; instead, it was restructured into a formal system that could fit within the state’s vision of progress. Singapore’s experience suggests that everyday practices can become part of modern urban life if they are recognized as living and evolving. Ultimately, the lesson from Singapore’s hawker centers is that planning should engage with culture as a dynamic, participatory process. While this process has limitations, it also shows how planning can accommodate cultural practices rather than simply displacing them. with cultural practices rather than simply displacing them. By acknowledging the fluidity of everyday life and giving agency to local communities, planning can move beyond managing space toward cultivating belonging and identity in an increasingly globalized world.

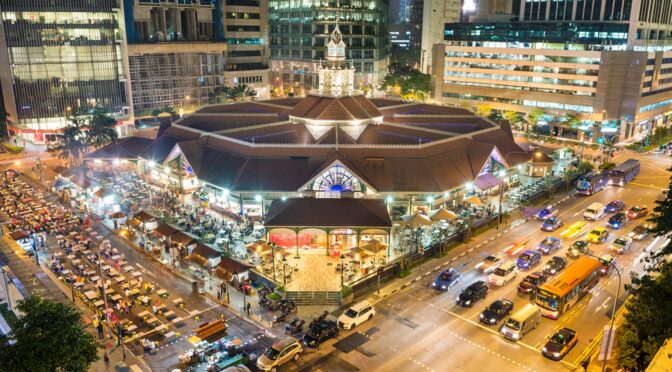

Source: Photo of a hawker center in Singapore | Photo: Aapo Haapanen

Source: Maxwell Road Food Centre, 1980s | Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore

The market’s predecessor building was already designed as an octagon | Photo: Stephane Lemaire