How global heritage conservation neglects lived heritage and daily needs in favor of tourism in Port-War Syria

By Riley Pierringer

Introduction

In December 2010, a wave of pro-democracy protests, later dubbed the “Arab-Spring,” swept across the Middle East and North Africa in response to decades of corrupt political institutions and stalled socioeconomic mobility. Some uprisings toppled long-standing dictatorships, while others were met with state-sanctioned violence and prolonged instability. In Syria, demonstrations against President Bashar al-Assad’s authoritarian regime devolved into a horrific civil war within just 6 months that lasted for 14 years. When anti-regime rebel forces recaptured the capital city of Damascus in late 2024, forcing Assad to flee to Russia, global observers broadly recognized the conflict as nearing its end (Laub, 2024).

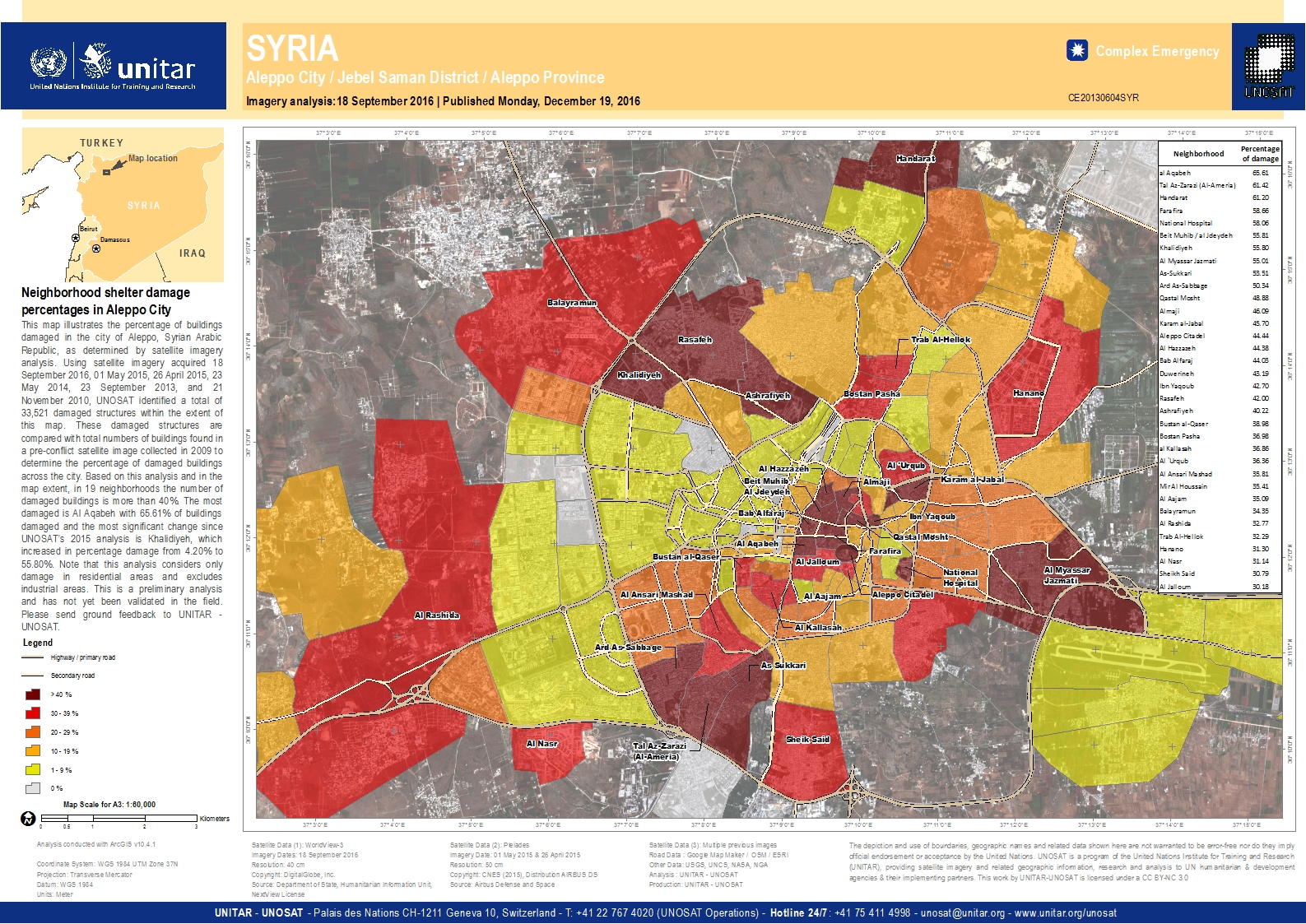

Reliable data remained scarce during the conflict, and the full scale of destruction and loss of life will likely never be known, but UN investigations in 2023 estimated 5 million Syrians fled the country and 7 million were internally displaced. The city of Aleppo alone hosts an estimated 3.5 million people dependent on humanitarian aid as of 2024, the largest population anywhere in the country (UNOCHA, 2024). Aid distribution and peacebuilding efforts have unfolded along multiple, often incongruent, pathways. Between 135 and 200 NGOs are actively operating in Syria, with additional NGOs supporting recovery efforts from neighboring countries (Alhousseiny et al., 2021; Beaujoaun, 2024; SIRF, 2025; Timings, 2021).

Given its extraordinary aid-dependent population, Aleppo serves as a key case for examining the complexities of Syria’s post-war recovery, where competing recovery agendas from numerous actors have left Aleppines balancing mourning, survival, and long-term reimagining as they rebuild their war-torn city.

Analysis

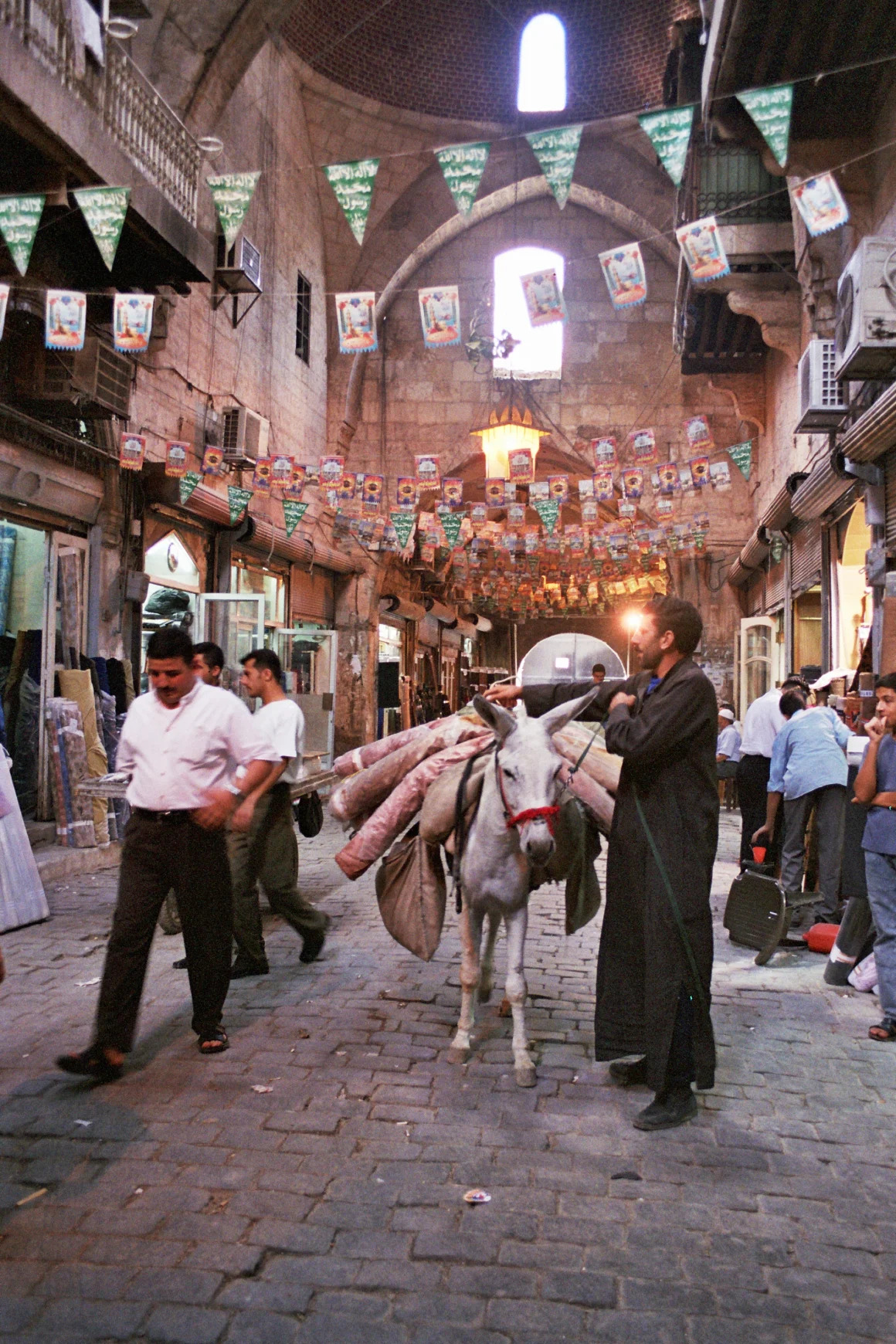

Aleppo is often defined by its status as one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities, which has contributed to its rich architectural heritage and dense urban fabric (Ibrahim, 2020). What keeps the city alive are the everyday patterns of urban life, cultural traditions, and social exchange. Before the civil war, residents often strolled in historic souks, tended to courtyards, gathered in neighborhood cafes, and maintained shared alleyways. These acts nurtured deep emotional bonds between people and place, and such attachments can be reflected in the regular practice of using personal identifiers like “ḥalabī,” meaning “from Aleppo” (Muhesen, 2025).

The city’s antique reputation took on new administrative and symbolic weight once UNESCO formally designated the Old City quarter as a World Heritage Site in 1986, shifting planning priorities toward heritage promotion and global tourism (Vincent, 2004). While this heightened Aleppo’s international profile and increased the city’s political importance, it also turned Aleppo into a living museum, overshadowing the everyday experiences of lifelong residents in favor of UNESCO monuments. When the civil war devastated much of this landscape, this pre-existing tension between external heritage agendas and the needs of Aleppines was magnified.

It is within this context that the contemporary “post-war revival” has unfolded. Reconstruction in Aleppo has largely followed top-down initiatives prioritizing iconic monuments such as the great Umayyad Mosque or Citadel of Aleppo over local needs, reflecting the broader pattern in which internal and external actors curate selective narrative about Syria’s recovery, obscuring its reality (Munawar, 2002). These initiatives include the highly publicized work in the 14th-century Al-Jdeideh neighborhood of the Old City (Salahieh et al., 2024) and the reopening of the Aleppo Souk, the largest medieval market in the Middle East (Aga Khan Development Network, n.d.; Muhesan, 2025). Though it is an important landmark for the city, the prioritization of its restoration is questionable given that large residential areas remain uninhabitable, and millions of residents continue to rely on basic humanitarian aid for survival. In effect, resources are funneled according to international or state preferences rather than neighborhood-level heritage and public services, widening the gap between external agendas and local desires.

Public opinion data affirms the tension between institutional and economic priorities and local needs. In a 2022 survey of 1,600 people currently living in Aleppo, respondents preferred investing in public services, utilities, and security over restoring monumental sites (Isakhan et al., 2024). Although respondents expressed pride in their cultural heritage, they rejected UNESCO’s plan to replicate hundreds of Old City structures. Instead, they valued everyday spaces that once grounded their lives and favored reconstruction of closer, community-serving religious sites with forward-thinking modern additions (Isakhan et al., 2024).

Implications

The fragmented landscape of NGOs, state entities, and external donors in Aleppo is reminiscent of the case of Beirut, where NGOs have overtaken the role of the state in reconstruction efforts (Fawaz and Harb, 2020), leading to Fawaz and Harb’s (2020) argument for a greater presence of the Lebanese government to ground these recovery efforts. In the case of Aleppo, what remains of the Syrian government, such as the Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM), is now taking an active role alongside NGOs (Muhesan, 2025). However, state presence alone is insufficient to drive recovery efforts that go beyond rebuilding physical structures. To achieve such a transformation requires grassroots efforts incorporating community knowledge and amplifying previously sidelined voices.

As Shamsuddin et al. argue (2008), place attachment emerges through lived relationships with space and rebuilding that sense of place begins with reviving the spaces that sustained social life. While heritage restoration is important to Aleppines, everyday spaces are just as essential to recovery. Residents already have an articulated vision for reconstruction, one that does not put UNESCO at the forefront. The challenge, or rather the opportunity for international planning, is to hear those voices over the buzz of NGOs and geopolitics and thus restore a sense of place and belonging. Novoa and Aguilera (2025) argue heritage preservation must emerge from collaborative, grassroots knowledge production that elevates the stories and memories long excluded from official narratives.

Source: People walk near Aleppo’s Bab al-Faraj Clock Tower, Syria

Source: Pre-war photo.