Everyday acts of planning unsettle dominant narratives of urban transformation

By Drashti Talwani

Introduction

Dharavi, in the heart of Mumbai, is often described as one of the world’s largest informal settlements, home to nearly a million people within an area of just 557 acres (Global Press Journal, 2025). Many residents run small industries—recycling, pottery, leatherwork, tailoring, and food production—that support both their families and Mumbai’s wider economy (KCLAS, 2023). Over the last thirty years, Dharavi has attracted repeated attempts at large-scale redevelopment. From early proposals in the 1990s to the 2004 public–private partnership model and the recent 2022 proposal led by the Adani Group, officials have presented Dharavi as a “pathological” space (Kamete, 2012) that must be reshaped into something more orderly and modern, aligned with the vision of a “world-class” city (Pandya & Kalra, 2023; Kothari, 2024).

But Dharavi is not simply a passive target of redevelopment. It is also a place where residents have organized for decades to improve their neighborhood on their own terms. Through the collaboration of the Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centers (SPARC), Mahila Milan, and the National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF), people have created daily savings groups, produced their own maps and household surveys, and put forward alternative ideas for upgrading (Patel & Mitlin, 2001; About SPARC, n.d.). These efforts reveal a side of Dharavi that receives far less attention—a dense and active landscape of community leadership, negotiation, and everyday planning that challenge Northern histories and assumptions in planning (Roy, 2007). Taken together, they show how residents imagine the future of their settlement, even as official plans continue to circulate around them.

Analysis

Although Dharavi is often described through megaprojects and state-led plans, the everyday planning work carried out by SPARC, Mahila Milan, and NSDF offers a more grounded way to understand how the settlement functions (Patel & Mitlin, 2001; About SPARC, n.d.). This contrast between external plan-making and everyday life illustrates Roy’s (2007) argument that urban theory often draws on Northern histories and assumptions, even when applied to places with very different urban logics or rationalities in Watson’s (2003) terms. Kamete’s (2012) examination of how planning normalizes and pathologizes informal spaces speaks directly to Dharavi’s portrayal as an area needing correction rather than recognition.

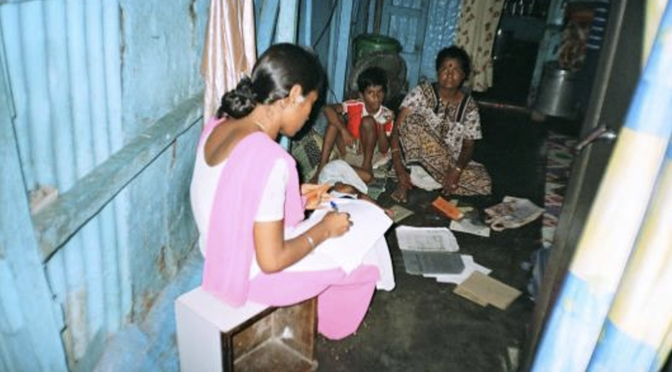

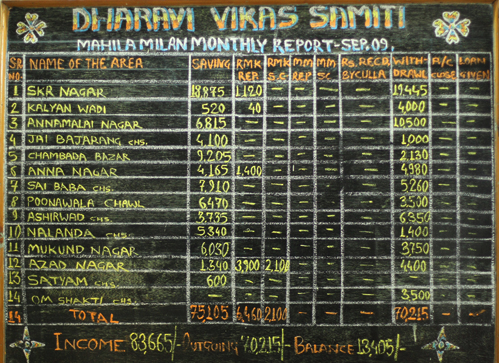

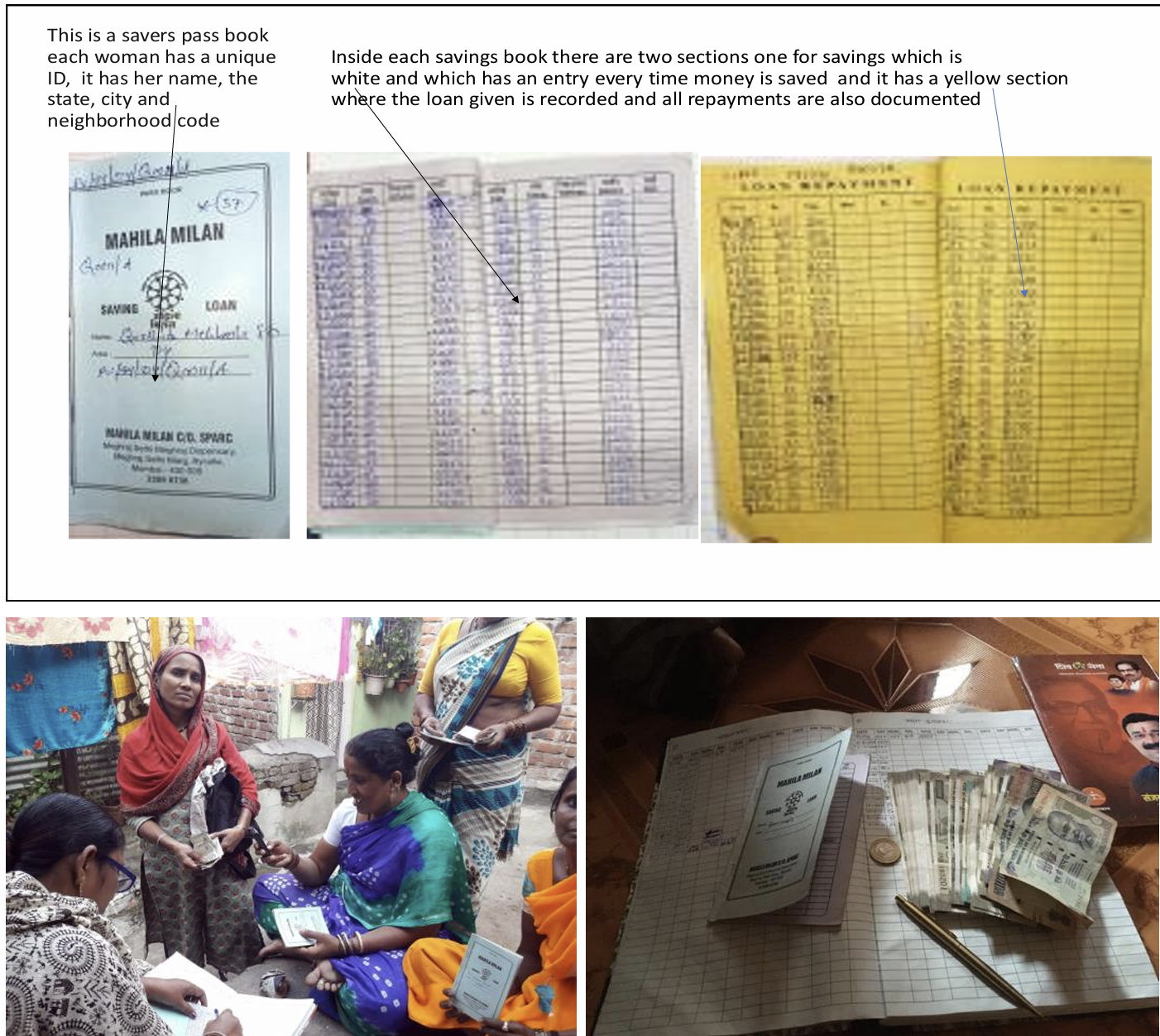

A good way to see this tension is through the women-led daily savings groups within the SPARC–Mahila Milan–NSDF alliance, which have existed in Dharavi for decades. These groups are small and simple in structure: women contribute a few rupees each day, collect the savings in rotating shifts, update handwritten ledgers, and meet regularly to discuss shared concerns. But the impact extends far beyond finance. Savings give families a buffer during fires, monsoons, and medical emergencies and provide spaces for women to speak collectively about housing repairs, sanitation problems, and upcoming redevelopment rumors, illustrating how everyday forms of collective action can create local systems of governance (Shafique and Taher, 2025) and allow people to build stability in environments shaped by uncertainty (Hernández, 2019).Savings groups also directly enable the collective work of enumeration by serving as the foundational governance structure, where trust, leadership, and accountability are built through everyday routines. Saving-group federations select and train community enumerators, manage the logistics of household surveys, and validate the information collected. Enumerations are then deployed through these same networks as a strategy for visibility, negotiation, and planning on residents’ own terms. The resulting data are used to prioritize upgrading as well as identify eligibility for rehousing (Patel et al., 2012; SPARC, 2021). In this way, savings groups provide the institutional base, while enumerations become the political and spatial expression of that collective organization.

Implications

Reflecting on Dharavi through savings groups and community-led enumerations pushes us to reconsider what planning knowledge looks like and where it comes from. These actions show that residents are not simply responding to redevelopment pressure; they are shaping the social, economic, and spatial life of their neighborhoods in ways that conventional planning frameworks often overlook. The savings groups reveal that planning begins long before official projects through collective decision-making and small financial contributions that build stability (Patel & Mitlin, 2001; Hernández, 2019).

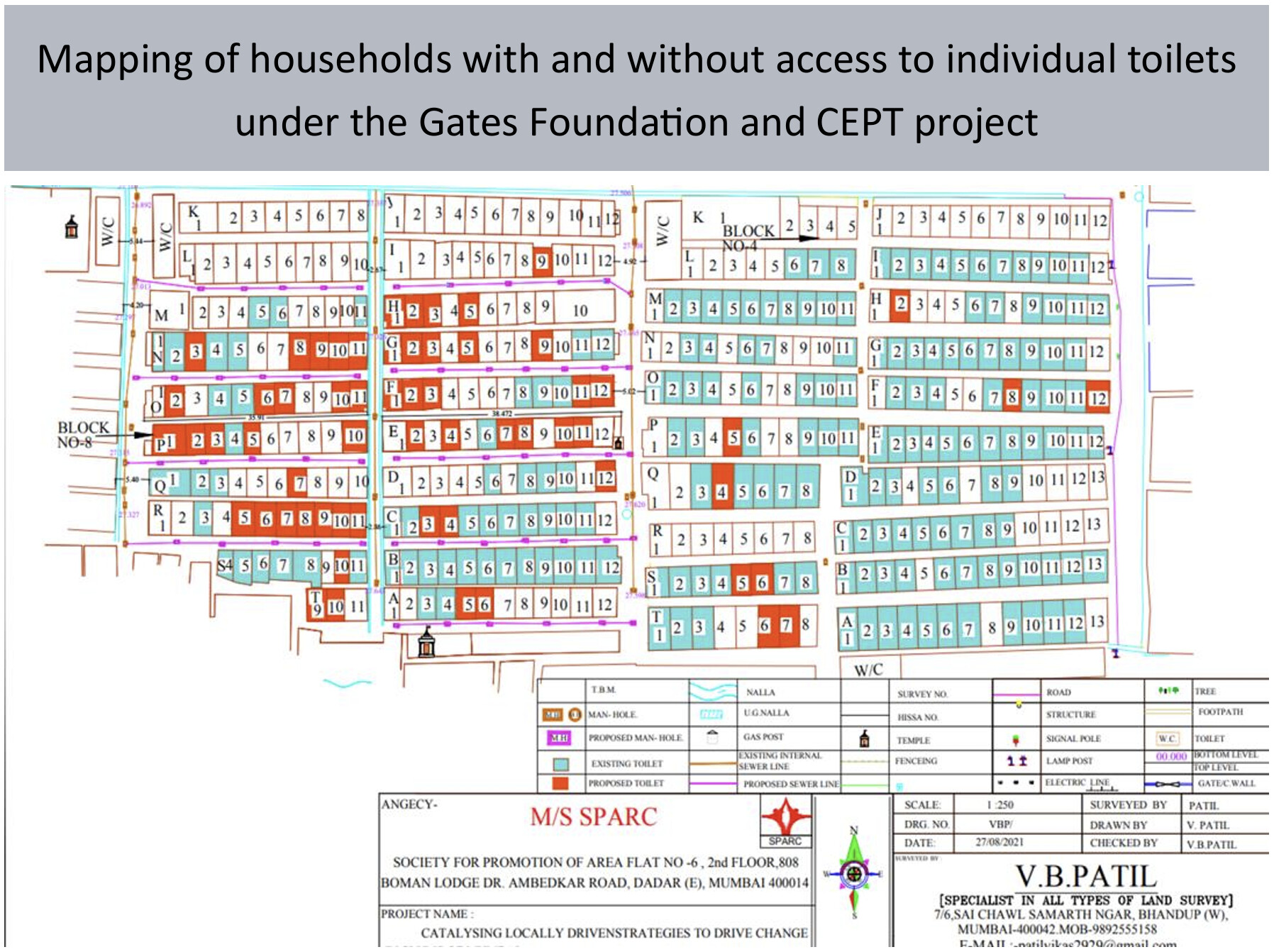

Through surveys and maps, residents “invent” their own planning spaces (Miraftab, 2004) to respond to redevelopment proposals based on a rationality rooted in lived experience rather than market-driven assumptions. By documenting households, workspaces, and social networks, residents generate knowledge that counters the state’s longstanding claim that Dharavi is unknowable or disordered (Roy, 2007). These efforts illustrate Watson’s (2009) concept of conflicting rationalities. While official redevelopment plans focus on formal housing and real-estate values, residents’ maps highlight priorities that formal redevelopment schemes routinely overlook like home–work proximity, spatial support for industries, and collective life patterns. Their maps make visible a rationality grounded in livelihoods, one that mainstream planning often struggles to capture.

Together, these practices disrupt the idea that planning expertise flows from institutions to communities. Instead, they show expertise already embedded in daily life, sustained by residents who organize, negotiate, and manage uncertainty long before a “world-class” vision emerges. They challenge the assumption that informality lacks value until replaced by formal planning. Instead, they demonstrate how communities create their own systems of order and propose upgrading models that preserve social and economic networks.

Source: Monthly savings report maintained by Mahila Milan women’s collectives in Dharavi.

Source: Women Managed Savings

Source: SPARC household-level toilet access mapping from the Dharavi sanitation project with CEPT and the Gates Foundation.