The use of Día de Los Muertos for city branding in San Antonio, Texas illustrates the contradictions of development in the Global North

By David Zarazua

Introduction

Dia de Los Muertos is a Mexican spiritual tradition that honors the lives of ancestors and deceased loved ones. Celebrated annually on November 1st and 2nd, every household sets an ofrenda decorated with Cempazúchiltl flowers, photos, food, and candles to invite the spirits back home through scents and memories. Public rituals are realized in graveyards and cemeteries, such as praying, cleaning, singing, and remembering. Since the creation of La Catrina by Jose Guadalupe Posada in 1920, the calaveras (skulls) made from sugar, chocolate, or tamarind have been popular symbols of the tradition’s identity.

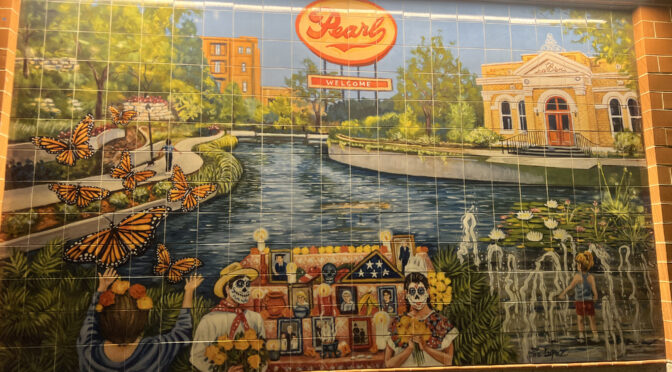

In San Antonio, Texas, the celebration of Día de Los Muertos constitutes a key element of placemaking among immigrants, creating a sense of belonging (Friedman, 2010) and assertion of presence within an unwelcoming social and political environment. Although the undocumented Hispanic community in San Antonio contributes to sustaining local economies (City of San Antonio, 2019) and forms vibrant social networks (Flores-Yeffal, 2019), immigrants are denied formal recognition and rights to the city and struggle with inadequate housing and access to infrastructure. Ironically, while the community is criminalized and excluded from formal planning systems, Día de Los Muertos has now been appropriated by city authorities into a festival full of Mexican folkloric symbols. While the community is invisibilized by immigration policies and dominant planning regimes (Mehta, 2016), their traditions and cultural heritage are used to brand the city for profit (Ong, 2011). Paradoxically, the festival coexists with the structural invisibility imposed by immigration policies and dominant planning regimes.

Analysis

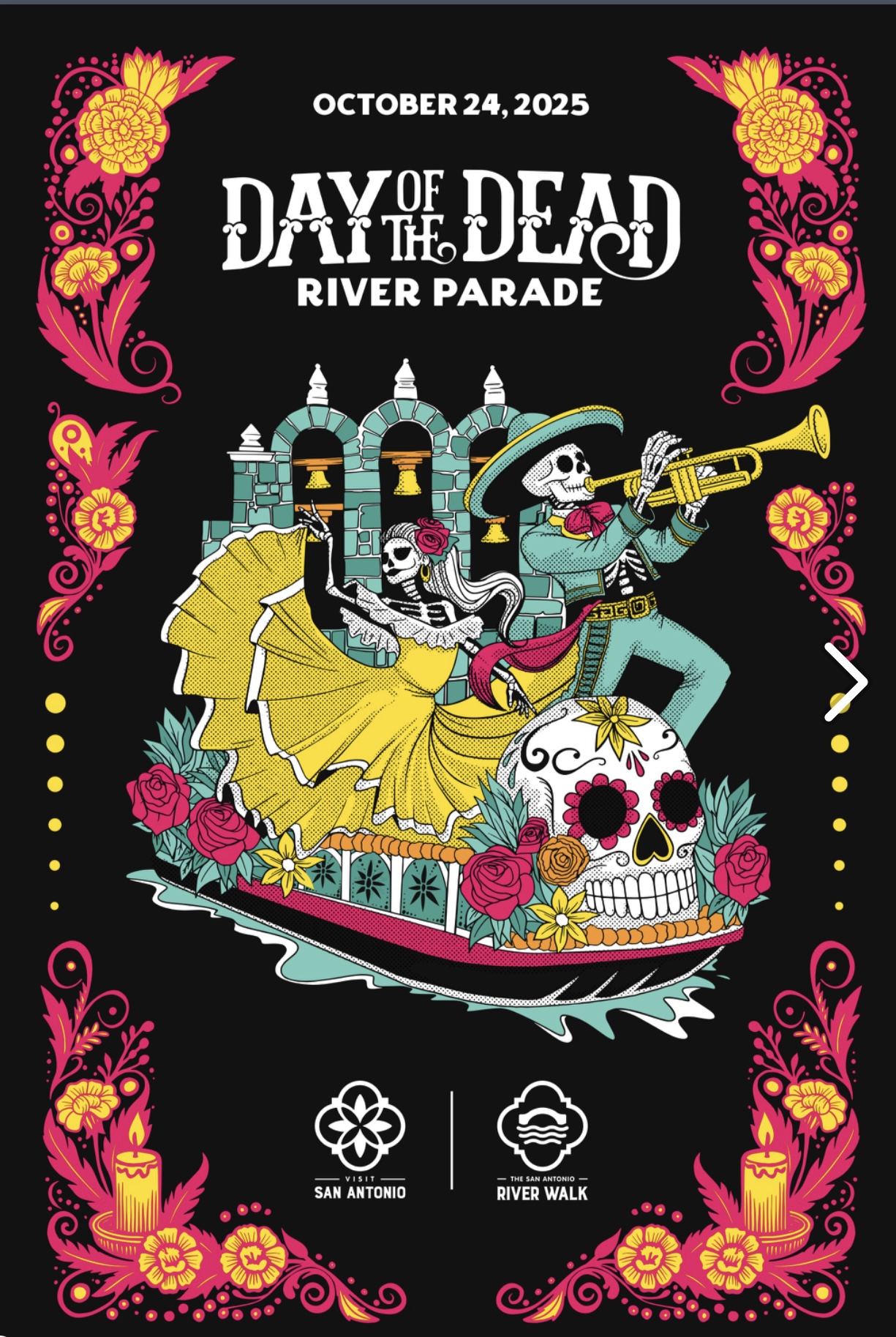

The practice of Día de Los Muertos in San Antonio demonstrates, on the one hand, how place-making functions as a tool of community solidarity through the co-creation of altars and public displays. Mexican and Mexican-American residents transform marginal residences into vibrant expressions of cultural belonging, showing how local rituals constitute forms of critical urban planning (Sweet & Ortiz Escalante, 2015). However, the local government has now commodified Día de Los Muertos for entertainment, tourism development, and financial gain for private brands and companies. The Día de Los Muertos celebration is replete with Mexican stereotypical symbols that do not necessarily represent this tradition such as mariachi, tacos, snakes, lucha libre “wrestling”, traditional clothes, and music from indigenous communities. The official Día de Los Muertos events are costly to access: for example, a ticket along the river to watch the parade costs from $20 to $60. Since tickets are mandatory to see the parade, this pricing has the effect of excluding people from public places. Tickets for other activities such as painting Alebrijes, visiting the Queen of Life and ofrendas, and attending the culinary fest tour range from $8 to $450, making them mostly inaccessible to low-income residents. During the parade, all the contingents present different brands like hotels, restaurants, TV channels, beer and soda companies, and the slogan “Visit the City of San Antonio, revealing the commercial interests behind the celebrations.

As a result of the exclusionary pricing, most low-income residents remain at home to celebrate Día de Los Muertos with their families and neighbors, pursuing informal practices based in community relations, storytelling, and memory (Ortiz 2022). The ritual practice becomes a vehicle for what Gudynas (2011) calls Buen Vivir, a pursuit of collective well-being, harmony, and dignity that challenges the rejection and humiliation imposed by the dominant rationalities of urban planning in the global north (Watson 2009). Drawing on Hernandez’s work (2019), residents can be understood as developing a counter-discourse to development and domination by pursuing an insurgent ritual that transforms fear into solidarity and visibility within hostile and toxic environments.

Implications

This case offers critical insights for rethinking international planning in the Global North through theoretical lenses from the Global South. The informal and communal practices found in Texas challenge dominant planning paradigms that equate legality with legitimacy (Sletto et al., 2025). Moreover, these practices resonate with Escobar’s (1996) critique of development, showing that “progress” and “modernity” in the Global North coexist with zones of exclusion that mirror those of the Global South. In the case of Día de Los Muertos in San Antonio, while state governance defines legality and order, undocumented communities practice their own spatial logics grounded in reciprocity, memory, and mutual care in an unwelcoming environment (Hernandez, 2019). Ultimately, the exclusion of the migrant community because of their legal status coupled with the extraction of their cultural practices within the same political geography presents profound, moral questions for the planning field.

The Día de Los Muertos celebration in San Antonio also illuminates the power of place-making and the importance of defending cultural and spatial identity in the face of displacement and invisibility. It invites a shift from viewing undocumented communities as “problems to be solved” toward understanding them as producers of knowledge, meaning, and spatial justice. Through their everyday practices and storytelling (Sandercock and Giovanni, 2014), these communities unsettle the boundaries between formal and informal, North and South, legality and humanity.

Riverwalk parade “Day of the dead” in San Antonio TX I. Photo Credit: David Zarazua

Riverwalk parade “Day of the dead” in San Antonio TX II. Photo Credit: David Zarazua

Source: San Antonio City Day of the Dead advertisement 2025