The connection between increased stormwater flooding and elite urbanism in Bwaise (III) in Kampala City, Uganda

By Ibrahim Bahati

Introduction

Within a 10-minute drive from Kampala City and just 6 minutes from Uganda’s esteemed Makerere University, you will find the informal settlement of Bwaise in Kawempe Division. Legend has it that the name of the community came from a local proverb: “Once grain is spilled, it is tough to gather.” This refers to the heavy mud and waterlogging that occurs after heavy rains, making the roads impassable. According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS, 2024), the three sections of Bwaise (Bwaise I, II and III) have over 90,000 residents and a mix of commercial, industrial, and residential areas (Nuwematsiko et al., 2022), making it one of Uganda’s most densely populated areas and one of Kampala’s largest slums. In Bwaise, 82% of residents live below the poverty line at $1 per day, 50% have never attended school, and 40% lack proper access to safe drinking water (Monitor, 01/05/2021). This article focuses on Bwaise III, where the Northern Bypass highway runs. This area experiences more severe stormwater flooding than other sections of Bwaise because of the expansion of large open-air sewage drainage systems from road construction.

Analysis

Politicians often blame the increased urban flood risks and related health issues on the informal residents in Bwaise III and their ostensibly illegal occupation of flood prone land. They claim that residents throw plastic bags into stormwater channels and thus worsen the flooding problem, while residents blame the government for failing to provide better drainage systems (Global Press Journal, 2018). However, these conflicting rationalities (Watson, 2003) obscure the colonial roots of urbanization in Uganda that created the conditions for informality and urban inequality. During colonial times, the British promoted racial segregation in the design of Kampala City, reserving safe spaces for white settlers while pushing native Ugandans to areas prone to flooding (Faria et al., 2021). Later, the 1951 Kampala City Plan aimed to create “African residential zones” in Naguru and Nakawa (factory areas) with the ulterior motive of extracting labor, controlling, and civilizing urban Ugandan residents to be “good citizens” who make up a “good city” (Byerley, 2013).

Today, Kampala City remains divided along socioeconomic class lines, with politicians repeating the same colonial narratives. This explains why, in general, development projects in Uganda are framed in a political language that stigmatizes urban informality, portraying residents in Bwaise III as not fitting the image of civilized urban citizens (Kamete, 2013). Similar to South Africa (Ngweya & Cirolia, 2020), the Ugandan government (through the Kampala City Council Authority – KCCA) also lacks clear guidelines for providing adequate housing for city residents. In such situations, road projects act as cosmetic additions to beautify the city, which heighten social inequalities under the guise of supporting global capitalism for third-world development (Escobar, 1996). As a result, top-down development projects like the Kampala Northern Bypass tend to obscure how elite urbanism (Moatasim, 2019) infiltrates city spaces. While informal residents are displaced through prolonged infrastructure developments, the urban elite is able to purchase land near the roads for high-rise buildings. Furthermore, Bwaise III lies in a catchment area for stormwater runoff from Mulago Hill, parts of Makerere University Hill, and the Kalerwe informal market. Because the project lacked a proper plan for installing an effective drainage system (Kasimbazi, 2018), the construction of the Northern Bypass contributed to the loss of wetland habitat and exacerbated the flooding problem. Although conventional approaches to informal urbanism “hinge on discovering technical definitions and solutions to ‘problems’ of informality” (Kamete, 2013: 647), technical solutions overlook the fact that “politics, contexts, and history matter” (Kamete (2013: 648). Ignoring that Bwaise III has historically been a wetland and an assemblage of stormwater from neighboring areas creates a technical oversight that informal urbanism gets blamed for.

Implications

The interconnection between stormwater flooding and people in Bwaise is constitutive of the embodied relationships typical of informal urban settlements. Like Ranganathan (2015) shows in the case of Bangladesh, the complex assemblage of stormwater, people, and their built environments challenges the tidy descriptions of urban place-making in Uganda, revealing that drainage infrastructure is “integral in the making of capitalism, space, and ecological risk in the cities in the global South” (Ranganathan, 2015, p. 1301). In Bwaise, urban place-making is an embodied experience, where human bonds and activities are adjusted to the flows of water within the liminal parts of the city (Shamsuddin & Ujang, 2008). While contending with flooding problems for their everyday survival, people are “…forced to reweave [their] connections with the larger world by making the most of its limited means” (Simone, 2004, p. 411). Residents develop survival tactics such as youth-led slum tourism (Monitor, 01/05/2021) and joining women’s credit savings groups, which train women to make cooking briquettes from solid waste management (Kiiza, 2023). Others sell food, agricultural products, and daily use household items at evening street markets.

The assemblage constituted by stormwater and people in Bwaise III prompts us to consider how storm canals and wetlands become “fictitiously commodified—literally, by surreptitiously filling with mud and concrete—in order to maximize capital accumulation” (Ranganathan, 2015, p. 1315). The construction of the Northern Bypass exemplifies corporate encroachments that favor elite urbanism over a community-centered approach to city development. Attitudes that normalize flooding as part of informal urbanism only serve to rationalize a worldview in which city residents are made to question their right to belong in the city (Baqai, 2025), instead of viewing elite urbanism as the actual problem. Therefore, Ugandan city planners need to start engaging residents of Bwaise III beyond neoliberal city development frames of renewal, improvement, and rebuilding by highlighting their embodied experiences of knowing, sensing, and being.

Source: Stormwater floods in Bwaise.

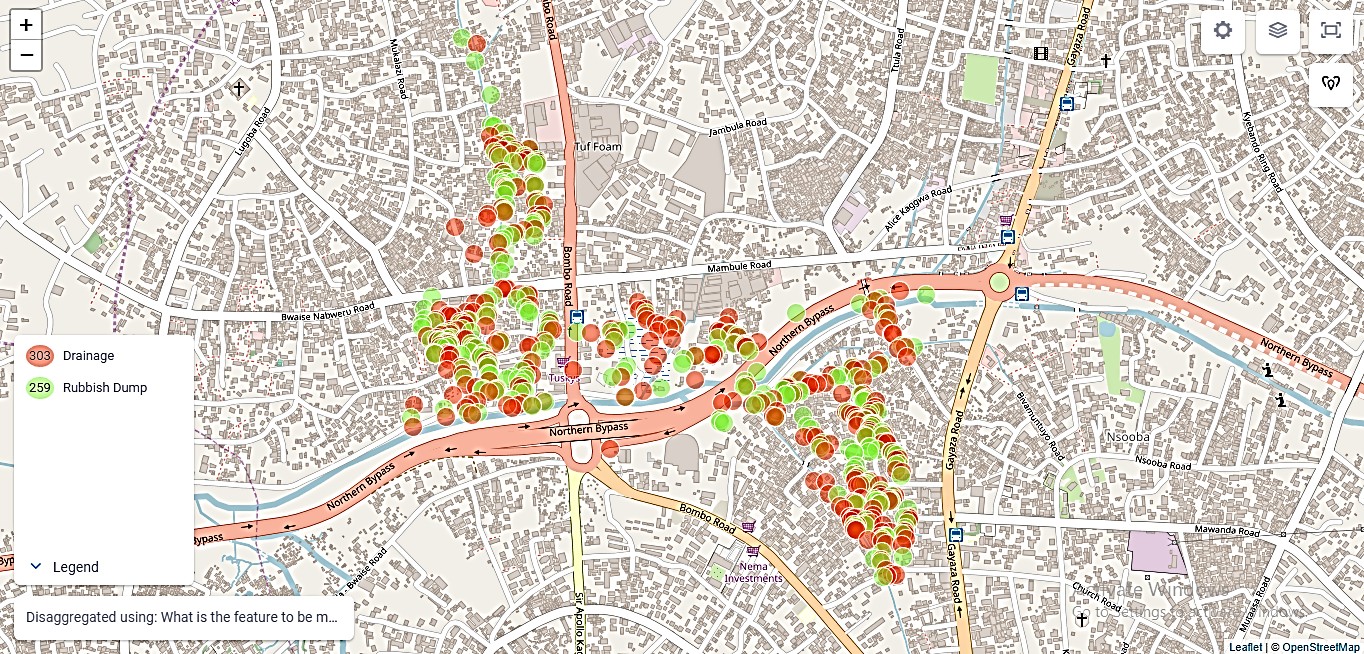

Source: Youth Mappers are tracking key flooding sites across all of Bwaise using a community-centered approach.