BY SUSANNA SHARPE

An image is a bridge between evoked emotion and conscious knowledge; words are cables that hold up the bridge.

—Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, 1987

When Chicana author, cultural theorist, and feminist Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa died in 2004, she left behind not only a strong literary and scholarly legacy but also a complex and rich archive. Anzaldúa’s closest friends knew of the author’s penchant for documenting her creative process, and such materials are plentiful in her archive. But the archive also contains a diverse assortment of ephemeral materials that document the author’s work habits, personal and spiritual practices, and lifelong struggles with her body and illness until her death at age 61 from complications of type 1 diabetes.

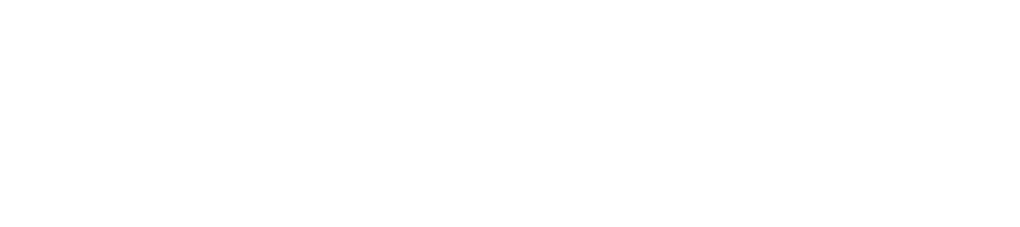

In her curatorial work at the Benson Collection, Gilland became intrigued by how Anzaldúa used visual expression to think, to write, and to teach. She turned to a series of transparencies that Anzaldúa used at workshops and lectures, which the author referred to as “gigs.” This led to the exhibition Between Word and Image: A Gloria Anzaldúa Thought Gallery, which opened at the Benson in May 2015. The exhibition also included audio from some of Anzaldúa’s talks. In her introduction to the exhibition, Gilland wrote the following:

“A self-described ‘Chicana, tejana, working-class, dyke-feminist poet, writer-theorist,’ Gloria Anzaldúa also saw herself as a nepantlera, one who navigates a liminal space between worlds, identities, and ways of knowing. Just as fluid movement between English, Spanish, and Nahuatl was central to Anzaldúa’s teaching and writing, so too was the interplay between words and images an essential element of her self-expression. These vivid documents provide an intimate view into Anzaldúa’s creative process and demonstrate the centrality of imagination and visuality to the author’s theories of knowledge and consciousness.”

Since March of 2016, the Anzaldúa exhibit has traveled to Mexico City; Vienna; Augsburg, Germany; and the campus of Colby College in Waterville, Maine. Throughout this journey, diverse audiences have interacted with Anzaldúan thought in a variety of venues, from art museums and gallery spaces to public and academic libraries. What layers of meaning can be added to Anzaldúa’s work when it is presented to new audiences in new contexts? This article gathers the words of curators, organizers, and students involved in these different installations as they reflect on its meaning.

First Stop, Mexico City

Entre Palabra e Imagen: Galería de Pensamiento de Gloria Anzaldúa traveled to Mexico City in March 2016, where it opened at Casa de Cultura de la UAEMéx, a cultural center of the Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, followed by Centro Cultural Border, a nonprofit space promoting contemporary arts and culture. This was the first display of Anzaldúa’s images south of the Río Bravo/Rio Grande, and it coincided with the translation into Spanish of Borderlands/La Frontera (2015) by the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) for a Mexican and Latin American readership. UNAM collaborated to bring the exhibition, and hosted an opening talk by Julianne Gilland, artist and art critic Mónica Mayer, and art historian/critic Karen Cordero at the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) on the eve of the opening. Artist and scholar Nina Höchtl and professors Coco Gutiérrez-Magallanes and Rían Lozano curated the exhibition, adapting it for a Mexican audience. Höchtl, Gutiérrez-Magallanes, and Lozano asked:

“How do we read and revisit the textual and visual Anzaldúa in the present, here in Mexico? What role is played by the borderlands we inhabit, the ones in which we live and survive? In what sense does Anzaldúa help us to give voice to, and make sense of, the ways in which relationships of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and class play out in Mexico and in borderlands? What is the relevance of Anzaldúa’s thought and her intellectual and visual propositions today?”

More than a year after the exhibition was first opened to Mexican audiences, Höchtl, Gutiérrez-Magallanes, and Lozano reflect on its impact in the context of Mexico’s current reality: “[Given] the violent times we live in, Anzaldúa’s work is a breath of life and hope. We observe that students, mostly, see in her work a universe of possibilities in terms of ways to resist the violence inflicted upon our individual and social body. She gives us elements for thinking of the self, both individually and collectively, in affirming ways and in modes of resistance.”

The Mexico City curators reflect on ways in which Anzaldúa’s thought challenges notions of knowledge and the university: “We strongly believe, and our experience tells us, that through the use of Anzaldúan thought and methodologies, theories and practices, the source of knowledge from the university is dislocated to the personal and collective histories outside of it in a conflictive and productive manner. Anzaldúa’s conocimientos visualize knowledge production as (dis)located in multiple spaces with complex and challenging relationships to race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, and the hegemony of knowledge.”

Autumn in Vienna

Artist and curator Verena Melgarejo Weinandt brought Between Word and Image to Vienna in fall of 2016 through a kultür gemma! fellowship at the Vienna City Library and in collaboration with the Austrian Association of Women Artists (VBKÖ). In its Vienna incarnation, the exhibition was renamed—A(r)mando Vo(i)ces: Una galería de pensamiento de Gloria Anzaldúa—a bilingual play on words that makes reference to both love and combat. Melgarejo brought in new voices in dialogue with the Anzaldúa materials: Afro-Dominican author Yuderkys Espinosa Miñoso presented a talk via video, “Feminisms in Latin American and Antiracist and Decolonial Efforts.” A children’s workshop featured poetry by Afro-descendant and Indigenous authors from Latin America and a mapping project. Anzaldúa’s transparencies served as a stimulus for a group of photographers—“Nepantleras fotografiando”—who created and exhibited work in response to the exhibition. Selected books from the Vienna public library were displayed to accompany the exhibition’s theme.

Reflecting on the project’s impact, Melgarejo says she was pleased “to able to contextualize Gloria Anzaldúa’s work not only in academic ways but together with the outcomes of the children’s workshop and the photography workshop within the Latinx community in Vienna. The public library was the perfect space for this. On a historical level, I think it was great to be able to contextualize her knowledge, which is (almost violently) ignored in the German-speaking context.”

Next Stop, Colby College, Waterville, Maine

In summer 2016, Rebeca Hey-Colón, assistant professor of Spanish at Colby College, spent two weeks working with the Gloria Evangelina Anzaldúa Papers in the Benson’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Reading Room. “The richness of the materials I encountered amazed me. It also made me realize that most of the people in my small liberal arts college in Maine had likely not had the chance to experience this archive firsthand,” she said.

Hey-Colón’s enthusiasm was such that she was able to arrange for an installation of Between Word and Image at the college library in March 2017, as well as a lecture by Julianne Gilland. “It was especially significant for me to arrange for this visit of Anzaldúa’s materials, given that she herself had come to the college in 1991 to give a lecture titled ‘Post-Colonial Stress: Intellectual Bashing of the Cultural Other,’” said Hey-Colón.

“Many who have read Anzaldúa for years did not know she was also a very visual thinker,” she continued. “Having the chance to see her drawings has been a thought-provoking experience for them. The exhibit was also integrated into classes in Latinx Studies housed in the Spanish Department, as well as courses in the Art Department, and in the Women’s, Gender, and Sexualities Studies Program.”

The exhibition at Colby, remarks Gilland, is “a mark of how much Anzaldúa’s work has entered the canon of US higher education and letters.” In a presentation on the Anzaldúa archive to a senior seminar in the Colby Spanish Department, Gilland addressed the mythological aspects of Anzaldúan thought:

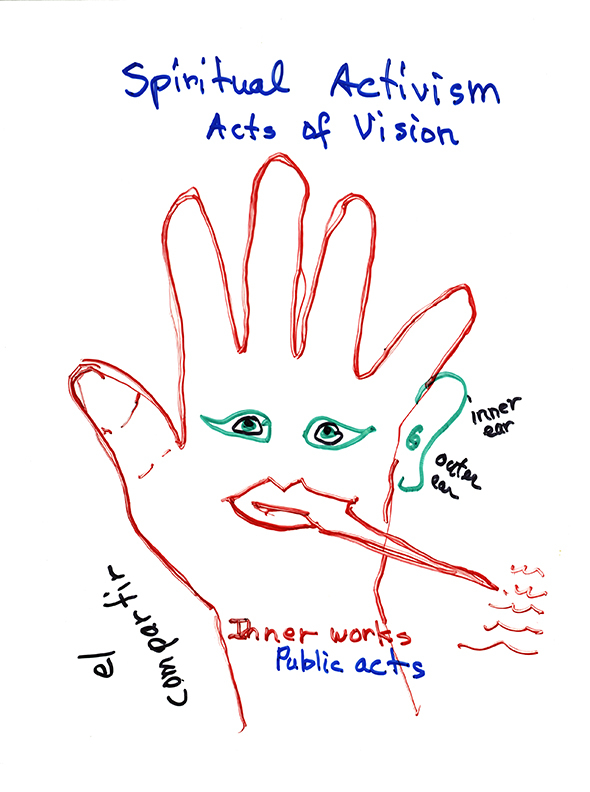

The story of the Aztec goddess Coyolxauhqui is a key metaphor for Anzaldúa. According to the myth, Coyolxauhqui, goddess of the Moon or Milky Way, was dismembered by her brother (or son), the God of War Huitzilopochtli, for not wanting to leave their sacred mountain and resettle in Tenochtitlan. Dismembering Coyolxauhqui enables Huitzilopochtli to lead the Aztecs to their new home, Tenochtitlan.

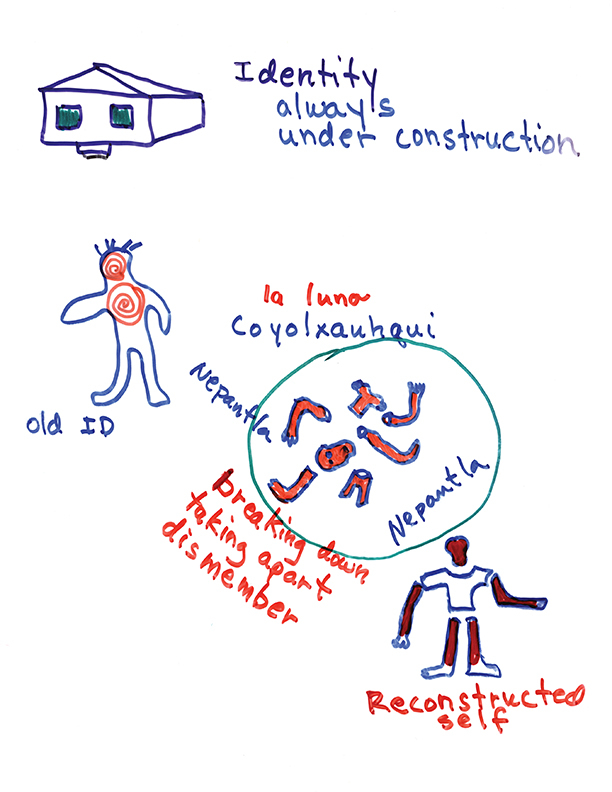

Anzaldúa writes about going through a “Coyolxauhqui process” with her body, and her body’s memory, every time she writes. She calls it painful, violent work. Writing, for her, consists of composing fragments, putting them here and there, changing them, fleshing them out. It makes her feel as though she is taking herself apart, dismembering herself “bone by bone” and putting herself back together. She describes it as a cycle of death and rebirth, for both author and work. This process for her is Nepantla, a journey between worlds, or a passing from one world to another.

Anzaldúa groups the concepts of Coyolxauhqui, and Nepantla together in conceptualizing her writing process, also including the idea of the cenote, a reservoir or dreampool of memory and creativity, all of which are represented in the images on view here in the exhibition.

Anzaldúa in Augsburg

At its most recent stop, in late March 2017, A(r)mando Vo(i)ces opened in two locations in Augsburg, Germany. Its installation at the Public Library of Augsburg from March 27 to March 29 coincided with the international conference “Beyond Borders: Literaturas y culturas transfronterizas mexicanas y chicanas,” organized by professors Dr. Romana Radlwimmer and Dr. Hanno Ehrlicher from the University of Augsburg. A longer exhibition ran from March 28 to April 30 at the Kulturcafé Neruda.

Radlwimmer is assistant professor in Spanish Literatures, University of Augsburg. She wrote about Anzaldúa in Augsburg: “The exhibition openings were accompanied by an artistic program: a transborder literary reading and music with local artists but also with Chicana writers like Norma E. Cantú. Both locations ensured a direct and diverse communication with community life in Augsburg. In the aftermath, the exhibited imprints of Anzaldúa’s drawings were given to the Kulturcafé Neruda, an artistic, migrant-friendly space directed by Turkish-German artist Fikret Yakaboylu. The artifacts will be on display there on other occasions in future years. Thus, Anzaldúa’s iconographic work will impact the German and German migrant community on a long-term basis.”

A(r)mando Vo(i)ces was curated in Augsburg by visual artists Höchtl and Melgarejo Weinandt, and was funded by the Kurt-Bosch-Stiftung.

Next on the Itinerary

According to Julianne Gilland, the Anzaldúa exhibit’s traveling days are not over. An exhibition is planned for fall 2017 at the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP). An art space in Chiapas is another future venue. In 2018, the VBKÖ will present an exhibition combining Anzaldúa’s drawings with work of Vienna-based artists inspired by her. Gilland remarks on Anzaldúa’s accessibility to a cross section of audiences: “It has been wonderful to see how this traveling exhibition has really taken on a life and energy of its own, with diverse venues around the globe continuing to want to show the work and engage with the archive. I think it really speaks to the appeal of Anzaldua’s thought and practice for both scholarly and creative communities, and the deep resonance that questions of identity, migrations, and memory offer for us all.”

***

Anzaldúa in Mexico: Student Reflections

Students were integral to the Anzaldúa exhibitions in Mexico City in many ways, assisting with translations, audio recordings, readings, and performances related to the exhibitions. Some of the students in Mexico City shared their reflections about Anzaldúa’s impact on their lives.

“For Anzaldúa it is important not to flee from pain. She breaks that binary between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ emotions. And more importantly, that pain has to do with the many violences she lived: a colonial wound, racism, classism, grave health problems . . .”

—Valerie

“She wasn’t concerned about the problem of the distance between theory and practice, because in her life she wove them together. . . . Nepantla has helped me understand how to work on institutional criticism. To understand tension as a space for creation.”

—Mauricio

“looking at her drawings, her altar, her house, activating intimate talks about her with strangers also pierced by wounds, listening to her voice whispering ideas she developed after what i have known, was like looking into an obsidiana mirror, the smoky mirror, the shadow-sided one. in my very own conocimiento genealogical tree, i have set her in as my symbolic grandmother.”

—Alejandra

“Lo que nos lega el archivo de Anzaldúa: la invitación a hablar, a dar cuenta de nuestra propia archiva ante los silencios ensordecedores que borran cuerpas y conocimientos otros. Una lengua puente: la supervivencia de nuestro pasado cuando se supone que no existiéramos . . .”

—Jaime

Note: English translations of Valerie and Mauricio by the editor; alternative spellings and capitalization in both languages per originals.

Susanna Sharpe is the communications coordinator at LLILAS Benson and the editor of Portal. She is grateful to Julianne Gilland and to all of the other curators mentioned in the article for their assistance on this piece.