ILASSA STUDENT CONFERENCE PAPER

BY ITZA A. CARBAJAL

On March 24, 2015, Soad Nicole Ham Bustillos, age 13, and three other young Hondurans, all high school students, were murdered in Tegucigalpa. Less than 24 hours earlier, video footage had shown them publicly protesting against recent changes imposed by the Ministry of Education. The footage displayed identifying information, including the faces of the minors, names or ID tags, school uniforms, and location. It also captured in real time the students’ anger and frustrations, serving as evidence of a vexed populace. The video made the rounds on social networks shortly after Soad’s student group had gathered to protest. She never made it home that day, and her body was found strangled and beaten.

As researchers continue to explore the use of digital data, there exists a crucial need for caution. Similarly, groups and individuals who work on social justice issues in Latin America have increased their use of information-sharing online to spread the word of their plight and implore others to join their cause. How often do researchers consider their role and responsibility when using and preserving online born-digital data documenting activism in Latin America? If they do practice preservation strategies, how do they navigate issues of privacy and safety, while also subverting the possibility of providing intel for surveilling institutions? This article highlights some ethical dilemmas researchers face with regard to digital data, in hopes that researchers will further develop their digital sensibilities.

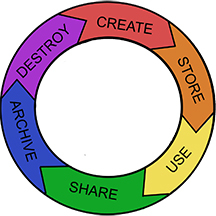

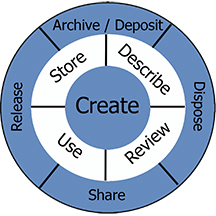

This research analyzes different aspects of the information lifecycle as it relates to the processes of handling digital data and engaging in digital scholarship. Utilizing an expanded model of the Information Lifecycle, I will focus on three areas, including the Describe, Review, and Deposit/Archive phases. These suggested stages highlight just a few approaches to cultivating a vigilant and more careful digital scholarship framework that considers both the needs of academic inquiry and the safety of the people captured through the data.

Information Lifecycle

When using online digital data, researchers must develop a better understanding of how information typically comes into existence. The Information Lifecycle Model (Figure 1) has historically been used to convey the different stages data typically undergoes. In my research, that model has been expanded to include the additional areas of Describe, Review, and Release (Figure 2). This expanded model avoids a strictly linear and chronological structure and instead focuses on a multilayered, nonsequential, and nonlinear approach.

The multilayered design illustrates how information goes through different layers of existence that often occur simultaneously and, depending on the user, can be acted on or ignored. In addition, the nonsequential aspect facilitates an understanding that information can remain in a static state, can be handed over to another caretaker, or can cease to exist.

The expanded model more closely aligns with researchers’ tendencies when handling digital data. Researchers of social movements typically start by either creating digital data, or harvesting data created by members of a movement. If the researcher creates the data or harvests raw data, she typically stores the data afterward. Given today’s unstable political climate around the world, including Latin American countries, the availability of collected data can jeopardize the safety of individuals the data includes. Social media, an exclusively online and public platform, has recently become the topic of cyber safety discussions as more state surveillance agencies such as the National Security Agency (NSA) and local police departments turn to public platforms in an effort to identify, criminalize, and persecute organizers.

Digital Activism Risks and Digital Freedoms

Given the fluid and intangible nature of digital media, researchers can easily forget the very real dangers participants may face when engaging in digital activism. Researchers, especially those not residing at the site of conflict, often communicate and engage with the work on the ground using information communication technologies (ICTs) such as cell phones, mobile devices, or the internet. Activist groups, in turn, share information with researchers and other members of the public through websites, blogs, and social networks. Some argue that these new possibilities have broken down barriers “created by money, time, space, and distance [with information] disseminated cheaply to many people at once.”1 Despite these new possibilities, one must avoid romanticizing ICTs, as many people around the world continue to struggle to connect, and there are numerous pitfalls of overindulging in digital engagement. One of the most fascinating and terrifying aspects of the relationship between social networks and personal information goes back to the fact that much of it is crowdsourced from the original creator and the creator’s immediate peers. Take face recognition, for example. Facebook has been said to have a 95 percent accuracy rate compared to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s 85 percent.2 Many factors contribute to the facial recognition algorithm’s success, but much can be said about an individual’s own contribution to the wealth of the personal information database. Researchers also play a crucial role in providing valuable information; for that reason, their responsibility toward activist and organizing groups is significant.

Depending on the country, activists and organizers may face dangers ranging from online harassment to death threats to actual persecution by either state officials or violent opposition groups. When contemplating the level of caution needed, one crucial step is to review the degree of digital freedom the particular country in question provides its population. Digital freedom refers to the levels of freedom countries grant their people.3 Depending on the defined areas of measurement, digital freedoms can include extent of internet infrastructure, financial barriers to web access, limits on what content can be displayed, and extent of user rights, from privacy to protections from repercussions for online activity and content. Several global reports, including those by Freedom House, Council of Europe, and the Global Network Initiative, have measured the extent of digital freedoms around the world, with many reporting a loss in digital freedoms as more governing bodies view online interactions as possible threats to their dominance. This article focuses exclusively on the relationship between user rights while online and the ethical responsibilities of researchers when interacting with and using digital data.

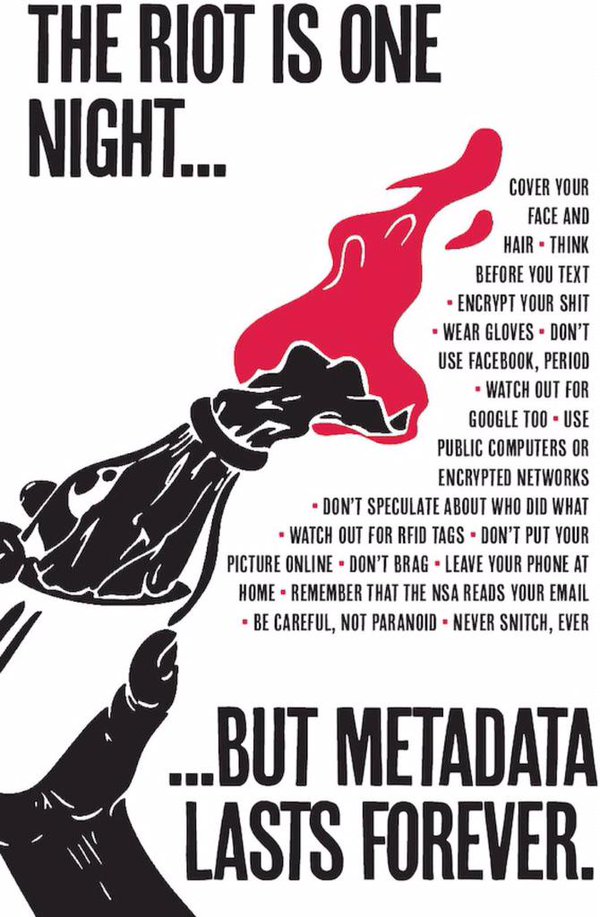

Ethics of Description

A recent trend in digital activism in the United States can function as commentary on the realities of other countries. In the wake of the election of Donald Trump, and the mighty opposition it has stirred in the United States, a particular graphic continues to spread in social network threads. During the inauguration protests, the phrase “The riot is one night . . . but metadata lasts forever,” set in a graphic design, spread like wildfire as the news of anti-Trump demonstrations circulated on people’s devices.4 As more people join efforts to dismantle the many oppressive systems in the United States and to actively combat the destructive policies of the current US administration, there appears to be a strong tendency to train new activists in ways that provide for their safety and security. Despite precautions, even if organizers and activists take necessary steps at one moment, this does not guarantee that personal information has not attached itself to their online presence ubiquitously. At many protests, digital data are now regularly captured using drones, video footage such as that recorded by body cameras, and protesters’ own mobile devices. When harvesting or accessing this sort of data, researchers must exercise caution, especially if they plan to store digital data sets for future use or to deposit their data at a university, research center, or other storage facility.

Ethics of Review

When researchers deal with digital data, the data review phase often comes as they contemplate depositing their research data in an archive or perhaps publishing that data in print or digital form. Yet the review phase is frequently overlooked, as it can appear as though all cautionary practices took place at the beginning of a research endeavor. This assumption can be misleading, especially considering the shareable nature of digital data. Even if a researcher makes all the correct decisions when selecting data to include or highlight in publications and presentations, this does not guarantee that others will follow suit with that same data. Depositing raw datasets is, thus, risky. Luckily, groups such as Documenting the Now, Witness, and others that work with Indigenous communities are actively developing standards and practices that emphasize notions of consent and safety regarding creators and their digital footprints.5 These measures become extremely important as state surveillance tactics increasingly utilize and invest in digital surveillance technologies. As digital information becomes more prevalent in scholarship, researchers will face an even greater responsibility to review all content before handing it over to another entity.

Ethics of Deposit and Archiving

For archivists, the relationship to researchers and their data is one of the most enduring and fruitful. Yet despite this longstanding relationship, levels of communication and understanding between archivists and researchers continue to fluctuate. When dealing with digital datasets, archivists find themselves in predicaments related to sharing and providing access online. As the chain of custody becomes blurry, even archivists who wish to protect creators’ personal information face obstacles ranging from having to locate subjects and obtain consent, to deciding what information to provide in online digital archival portals. Given that much of the information on who, what, when, and where stems from the researchers’ work, researchers are best suited to reviewing and identifying possible concerns. They can also help by filtering sensitive information prior to depositing data into an archival facility during any of the steps of the information lifecycle.

Approach with Care

Many of the issues discussed in this essay stem from a US perspective, given the author’s location and familiarity. Acknowledging this limitation, the topics discussed serve as a cautionary tale about long-established colonial practices embedded in institutions in the United States and many other countries. Researchers should approach digital data with the same care as when dealing with sacred or highly sensitive physical materials, for digital data does not exist independently from its creator.

For Soad and her peers, the shared video represented both a symbol of resistance and an opening to danger. Honduran news agencies claimed that Soad’s appearance on social networks had reached thousands of angry Hondurans at home and abroad, costing Soad her life. Others would claim that her appearance paved the way for more vocal and visible opposition in the many struggles Honduran students face. Both interpretations speak to the impact of Soad’s digital footprint, which amplified her protest efforts and clearly threatened some. Soad’s story is a warning to all: the lives of people captured in digital data exist beyond the screen, and their safety should be of the utmost concern, especially for those of us wishing to become an extension of the work being done on the ground.

Itza A. Carbajal is the daughter of Honduran immigrants, a native of New Orleans, and a child of Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. She lives in Austin, Texas, where she is pursuing a Master of Science in Information Studies with a focus on archival management and digital records at The University of Texas at Austin School of Information.

Editor’s note: This article is adapted from a paper presented by the author at ILASSA37, the 37th annual conference of the Institute of Latin American Studies Student Association, held at UT Austin in March 2017.

Notes

1. Summer Harlow and Dustin Harp, “Collective Action on the Web: A Cross-Cultural Study of Social Networking Sites and Online and Offline Activism in the United States and Latin America,” Information, Communication & Society 15, 2 (2012): 197.

2. Naomi LaChance, “Facebook’s Facial Recognition Software Is Different from the FBI’s. Here’s Why.” May 18, 2016. NPR All Tech Considered. Accessed February 25.

3. Sanja Kelly, Madeline Earp, Laura Reed, Adrian Shahbaz, and Mai Truong, “Privatizing Censorship, Eroding Privacy,” Freedom on the Net 2015, Washington, DC, and New York: Freedom House, 2015.

4. Anonymous, ‘The riot is one night . . . but metadata lasts forever’ ~ Security culture basics for #j20 #disruptj20, January 20, 2017, 11:15 a.m. Twitter.

5. Kritika Agarwal, “Doing Right Online: Archivists Shape an Ethics for the Digital Age,” Perspectives on History, American Historical Association, November 2016.

Bibliography

Benfield, Jacob A., and William J. Szlemko. 2006. “Internet-Based Data Collection: Promises and Realities.” Journal of Research Practice 2 (2): 1.

Buchanan, Elizabeth A. 2003. Readings in Virtual Research Ethics: Issues and Controversies. Hershey, PA: Information Science Publishing.

Harding, Sandra. 2016. “Latin American Decolonial Social Studies of Scientific Knowledge: Alliances and Tensions.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 41 (6): 1063–87. doi:10.1177/0162243916656465.

Lahman, Maria K.E., Bernadette M. Mendoza, Katrina L. Rodriguez, and Jana L. Schwartz. 2011. “Undocumented Research Participants: Ethics and Protection in a Time of Fear.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 33 (3): 304–22. doi:10.1177/0739986311414162.

Murray, J., and J.A.T. Fairfield. 2014. “Global Ethics and Virtual Worlds: Ensuring Functional Integrity in Transnational Research Studies.” In 2014 IEEE International Symposium on Ethics in Science, Technology and Engineering, 1–7. doi:10.1109/ETHICS.2014.6893453.

Ziccardi, Giovanni. 2013. “Digital Activism, Internet Control, Transparency, Censorship, Surveillance and Human Rights: An International Perspective.” In Resistance, Liberation Technology and Human Rights in the Digital Age, 187–307. Law, Governance and Technology Series 7. Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5276-4_6.