By BARBARA E. MUNDY

AN INVITATION TO THE 2025 LOZANO LONG CONFERENCE, “Urban Entanglements: Centering Marginalized Lives and Ecologies in Latin America,” allowed me to think about the question, Do Indigenous Ecologies Matter? I am an art historian, and I study the landscapes of the past, particularly the place known today Mexico City, the largest urban area in the Americas. It was once the capital city of the Indigenous people known as the Mexica, sometimes called the Aztecs, when it was known as Tenochtitlan. Thus, at its foundation, Mexico City was created because of Indigenous ecologies, meaning the ways its Indigenous residents thought about and interacted with the environment around them.

This is not the association that the city carries today. Instead, visitors and residents alike might call to mind its famously traffic-clogged roadways and the blanket of smog that hangs over the city in the dry season, or they might think of the informal settlements that climb up the surrounding hills and slopes of the large Basin of Mexico, as the area is known geologically. A satellite photograph from NASA reveals the current mancha urbana, which translates literally as “urban stain” (Figure 1), that spreads across the Basin. On the face of it, the experience of this modern metropolis might offer a resounding “no!” to the question of whether Indigenous ecologies matter.

But the historian’s job is to look through the phenomena of the present toward the past, with the conviction that everything in the present is the result of past events. At the same time, nothing in the present was ever the inevitable—similar to when two parents conceive a child. The gene pool of those parents establishes parameters of the child’s genetic code, but there’s no fixed certainty about the exact result. When I think about the ecological situation of the America’s largest city, I understand how today’s city is the result of phenomena—often human decision making—of the past. Showing individual phenomena, or revealing broader patterns among them, while at the same time resisting the narrative impulse to cast it all as inevitable, is how I see my role as an art historian. The “art” part of art historian comes in because the pieces of evidence I depend upon are works that communicate through visual codes, rather than textual ones.

After the Mexica founded Tenochtitlan, it would grow to be the largest city in the Americas. Because of my interest in the city, the ecologies of the Indigenous peoples of Mexico matter to me. But why should they matter to someone who is not a historian? The key comes in the lack of inevitability. If we, as modern citizens of the globe, want to think seriously and creatively about what options we have as we direct ourselves toward the future, we can be better informed, and more mentally flexible, if we understand the options that people of the past confronted, the decisions they made, and the reasons they made them. I see the importance of understanding the past not just as an exercise of learning not to repeat mistakes, but also as an effort to amplify the bandwidth of all possible futures. As Mexico City, along with the other large cities of the Americas, confronts a future whose normal uncertainty is amplified by climate change, understanding the ways that Indigenous peoples found to thrive within that same environment adds to the arsenal of valuable knowledge.

Ecologies of the Basin of Mexico

The depth of ecological knowledge of the Indigenous inhabitants of the Basin is suggested by a large painting by the twentieth-century Mexican artist Luis Covarrubias. Looking to the past, he imagined what the island city of Tenochtitlan and the surrounding Basin might have looked like around 1500 (Figure 2). The painting is dominated by the connected lakes of the Basin; it takes an oblique view from a midair point toward the active volcanos that lie to the southeast. In the midground, the island city of Tenochtitlan spreads out. The urban infrastructure that Covarrubias quite accurately captured in the painting reveals the profound environmental knowledge of the Mexica and other Indigenous peoples in the Basin. The island city was connected to the mainland by a system of raised roadways called calzadas that also served as dikes. By managing water levels, which could rise and fall dramatically during rainy and dry seasons, the Mexica were able to survive, even flourish, surrounded by an inland sea.

Their careful study of their environment led them to understand the agricultural potential of the freshwater lakes to the south, out of view in the Covarrubias painting. Moreover, they came to understand that rain and groundwater flowed into the shallow and largely saline central lake from the west, the area in the foreground of the painting. By creating dikes, they allowed the fresher water to sluice through and around the city. Additionally, they built a large restraining dike—visible in the painting as a curved line stretching from left to right—to keep saline waters from flowing back toward the city. By making sure that the shallow lakes around the city were filled with sweet water, the Mexica and others were able to unlock their agricultural potential.

The Plano Parcial de la Ciudad de Mexico

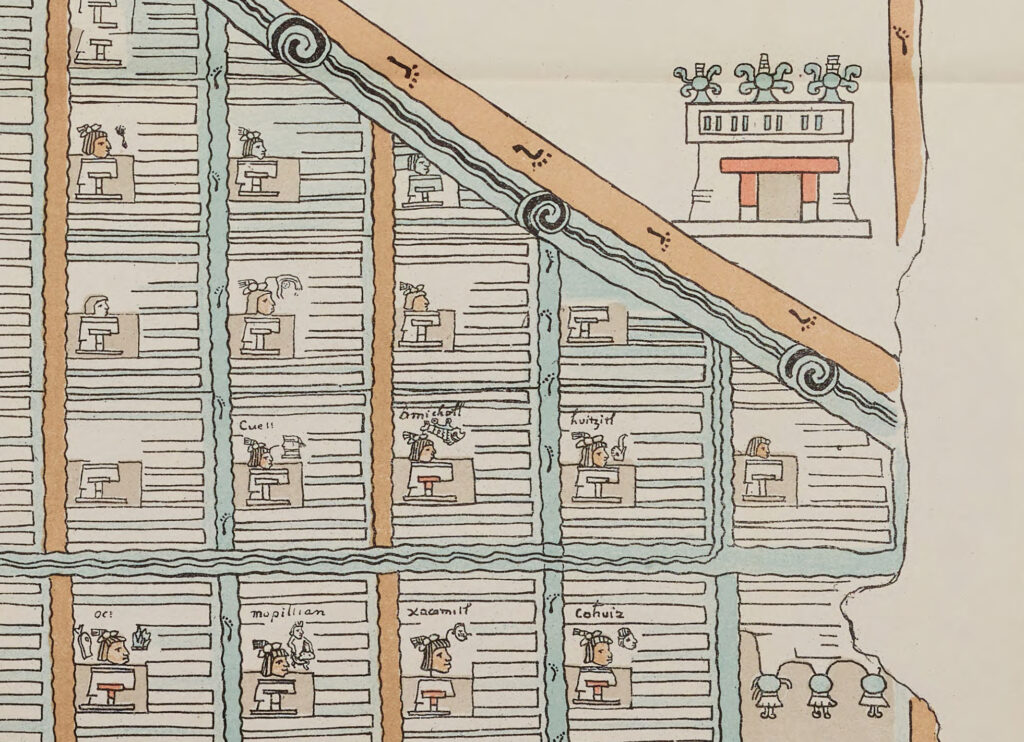

But true ecological knowledge comes from understanding not just how one system, in this case, a hydraulic system, works, but how multiple systems work together. We see the level of Mexica ecological knowledge in an extraordinary map known as the Plano Parcial de la Ciudad de Mexico (Figure 3). It is a large map, some 238 x 168 cm, almost precisely the size of the bed sheet for a twin bed. It shows evidence of having been looked at, cared for, and prized for perhaps as many as 500 years. The center area has largely worn away, because it has been repeatedly folded vertically for storage, so much so that the left side of the map is a now a separate piece from the right. While there is disagreement about where the map can be localized, there is uniform agreement that it shows some area in the Basin of Mexico. And it’s a very special geography: its gridded surface includes 400 or so plots, where strips of land alternate with strips of canals. Each of the plots is shown in a standard pattern with a standardized house, seen in profile, and above, a male human head connected to his Nahuatl name, written hieroglyphically, denoting the individual smallholder (Figure 4).

The map documents the Mexica attentiveness to the interaction of water, soil, microbes, plants, and humans—in the creation of raised-bed plots known as chinampas. “Chinampa” comes from the Nahuatl word chinamitl, meaning a kind of reed or cane enclosure. In swampy areas, the Mexica dredged canals, seen as the blue bands in the map. Understanding the value of the nutrient-rich bottom muck, they piled it high into flat-topped mounds, represented as ocher-colored bands. To prevent the water from eroding the soil, they planted small trees along the mound edges. The nutrient-rich soil allowed Mexica farmers to harvest at least twice throughout the year, one of the reasons that large human populations could flourish in the Basin. Not only did the small capillary canals provide irrigation for the plots, but they flowed into larger canals—also seen on the map—that offered a means of transport of crops to market.

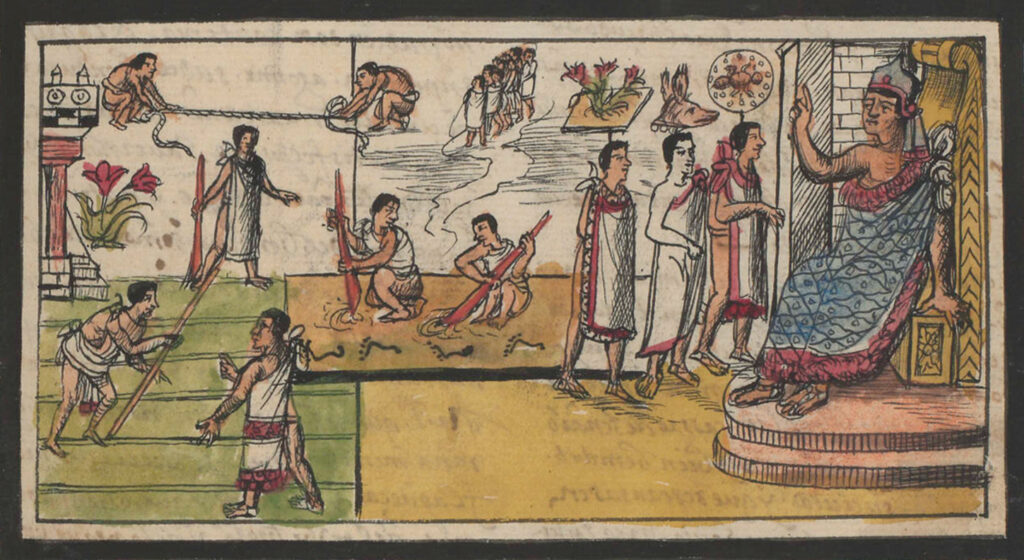

In an image from a sixteenth-century pictorial manuscript, Diego Durán’s Historia de las Indias, an Indigenous artist working for the Dominican friar created scenes to illustrate episodes in Mexica history. One, Figure 5, reveals the origins of the chinampa system that we see represented on the Plano, following the seizure by Mexica warriors in the reign of Izcoatl. On the right of the painting sits the ruler Itzcoatl, robed in blue and enthroned, as he commands the reallocation of chinampas to reward soldiers. At top left, two men measure lots with a rope stretched between them, while below them, men standing on the green ground of the chinampas are carrying out the reassignment. The beneficiaries of the booty appear on the Plano, as they wear their hair in a fashion reserved to warriors (Figure 4).

Understanding surrounding ecologies is the key to any successful agricultural practice, certainly, but the Mexica understood natural elements, like rain, groundwater, and earth, as sacred, expressing themselves in embodied forms that we call deities. Thus, they understood infrastructure projects, like the building of chinampas, as a new phase in the ongoing relationship between humans and all other partners in the divinely charged ecological system. The map reveals who the important ecological partners were in this landscape. At key junctures, where larger canals cross with roads, the Mexica erected temples to the rain deity, Tlaloc, marking the presence of this sacred embodiment in the landscape (Figure 4). Humans had desires and will, but so did water, represented by this deity. The Plano Parcial, in other words, shows a human attempt to integrate and balance these powerful natural forces.

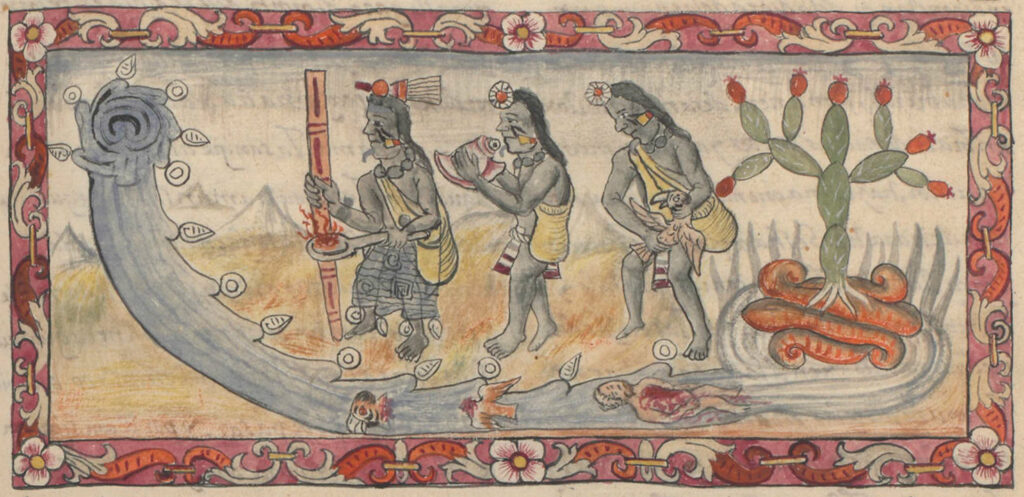

Because of this dynamic and animate environment, the Mexica seem to have viewed infrastructure projects not as humans imposing a correction on an unruly environment, to thereby bring it in line with human needs, but as a set of relationships of mutual benefit between humans and all other partners in the ecological system. The Mexica paid close attention to their partners. When any one of these projects was completed, Mexica priests made sure to inform and propitiate the appropriate natural force or deity. In a second image from Durán’s Historia, three Indigenous priests are pictured (Figure 6). Durán’s history tells of the construction of a new aqueduct in 1499. When it arrived to the city of Tenochtitlan, these priests made sacrificial offerings to the water deities. To signal this, the water is not just a passive stream; the artist shows it as if rearing up as the priests process toward it. They were anticipating, and hoping to positively influence, the water deity’s reaction. Despite their offerings, seen in the stream of water at their feet, the deity reacted badly to this piece of infrastructure, and Durán reports that the city flooded. That was a sign. Rather than pouring more energy into this failed project, they city’s engineers tried something else.

Chinampas and Indigenous Ecologies Today

Given the concrete extension of the mancha urbana, it might be surprising to realize that chinampas still exist in the southern Basin, in Xochimilco. But there is very little chance that they could be restored to anything like during their sixteenth-century apogee. Since the early twentieth century, Mexico City’s demand for reliable water for its residents has been sucking Xochimilco’s aquifer, and inadequate sewerage means that the canals are so polluted that they are better for cultivating flowers rather than edible food. So this particular Indigenous ecology may not extend into the future; nonetheless, Indigenous ecologies, with their insistence on the earth as a player in all relationships, with its needs and desires, may suggest ways for us to live in the future.

As history teaches us, Indigenous ecologies undergirded enormous cities like Tenochtitlan, today’s Mexico City. In this city, the Mexica carefully managed their relationship with water, and largely respected the domain of Tlaloc, confining urban development to solid land. The wisdom of their approach was revealed after the recent earthquake that hit Mexico City in 2017, killing an estimated 326 people. Víctor Cruz-Atienza, a professor of geophysics at the National University of Mexico, created a model to explain the intense shaking of the city, which devastated some neighborhoods but not others. He found that the seismic waves were concentrated in what is now the ancient lakebed. But the former carefully managed lakebed had, over the course of five centuries, been filled in for development. The desiccation of the lakes was a long process, spearheaded by Spanish colonists who brought with them very different understandings of ecology. They saw swamps as bringing more danger than benefit, believing them and their airs to spread disease. More importantly, they saw the environment as one that could be irrevocably transformed by the dictates of human will.

So Indigenous ecologies, with their built-in attentiveness to a dynamic and responsive earth, offer other models for human occupants. We find them eloquently expressed in Indigenous maps, which suggest alternate models of being in the world. These are built from relationships between organisms, where the human organism is obliged to consider the needs and desires of the earthly organism. The history of this relationship, like all relations, is not without conflict, and it changes over time, but knowing the past better equips us to have the knowledge, and the attentiveness, to deal with the future.✹

Barbara E. Mundy is professor of art history and Martha and Donald Robertson Chair in Latin American Art at Tulane University.

Notes

- Barbara E. Mundy, The Death of Aztec Tenochtitlan, the Life of Mexico City (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015).

- Teresa Rojas Rabiela, ed., La agricultura chinampera, Colección Cuadernos Universitarios, Serie Agronomía, no. 7 (Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, Dirección de Difusión Cultural, 1983).

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), “Mexico earthquake, 2017 – Forensic analysis,” September 11, 2024; accessed May 5, 2025.

- Derek Watkins and Jeremy White, “Mexico City Was Built on an Ancient Lake Bed. That Makes Earthquakes Much Worse,” New York Times, September 22, 2017; accessed May 5, 2025.