By C. J. ALVAREZ

RIVERS ARE HARD TO UNDERSTAND. I grew up in southern New Mexico about a mile from the Rio Grande. As a child, I didn’t think about where the river came from or where it was going. There were many ditches in my town, a capillary system branching off from the river, and it never occurred to me that it was anything less than an unmitigated good to drain a river for irrigation. The infrastructure of hydraulic engineering was so ubiquitous that it created significant distortions in my ability to perceive or even identify natural flows in the first place. It shaped the way I inhabited the region by fundamentally redefining the region itself, masking its true character, literally and figuratively overwriting nature.

I call this phenomenon environmental amnesia, and I have come to think it is perhaps the most important interpretive lens for understanding the twentieth century and beyond. It is a set of cognitive and physical distortions that we all suffer from to one degree or another. We often don’t know where we are, not really. Fewer and fewer people know the names of plants, local animals, migratory birds, even entire mountain ranges. Fewer and fewer people can orient themselves in space without technological prosthetics, let alone use their bodies to move across long distances. And rivers are among the most forgotten parts of the natural world.

The river of my childhood was a kind of hydrological vivisection, a part that did not stand in for the whole, something debased and ordinary. I reached these conclusions entirely subconsciously. Essentially, the built environment of hydraulic engineering made an argument, and I became convinced of its premise. The naked riverbanks once supported stands of cottonwood trees, but they were all gone and almost no one even remembered them. In their place were flood-control berms. The argument was: the riparian zone does not matter, the natural movements of the river must be disallowed, and its flow must be confined to preordained channels to subsidize monocropping.

In short, the river had no real meaning apart from its status as a “natural resource.”

To me, this is one of the saddest terms in the English language. Calling something a “resource” is a way of saying that the value of a thing can only be measured in terms of its usefulness to our species. It is a term that disrespects free nature, a term that makes it possible to grow up next to a river and never recognize it for what it is—something ancient and geological, a mountain remover, an entity that is never entirely fixed in its channel, something free and wild. Yes, as the cliché goes, water is life, but it is much more than that. Living things come and go, but the river belongs to the landscape in the deepest sense. It helps us understand the fundamental truth of topography.

Rivers are hard to understand because it is difficult to ask the right questions in the first place. Forty miles downstream from my childhood home, the Rio Grande becomes the international border between the United States and Mexico. To superimpose the function of territorial marker on a river further exacerbates environmental amnesia. And increasingly, the U.S.–Mexico border has become not just a cartographic abstraction but also a gigantic physical building site. This was the subject of my book Border Land, Border Water: A History of Construction on the U.S.–Mexico Divide. Most people who haven’t read the book think that “construction” must be synonymous with border walls. But anyone who has read it knows it is mostly a story about water and how hydraulic engineering on the Rio Grande has been far more transformative and invasive than any border fence on land.

When I first began researching the book, I knew I had to make significant amendments to my impoverished childhood understanding of the Rio Grande. So I went to the library, where there are a great many books that purport to be about the river. I checked them all out and found that almost none of them were about the river. They were about international treaty law as it pertains to the river, they were about the endless byzantine disputes over water rights, they were about irrigation projects and flood control, and they were about dams. In other words, they were, subtextually, about the unexamined sense of entitlement that permits our species to rip into any landscape we please to maintain physical settlements, political institutions, and markets.

This is an ideology that some refer to as human supremacy and others call speciesism. Both terms refer to the assumption that Homo sapiens are superior to other sentient forms of life, that our interests are inherently more worthy, and that our superlative rank gives us the right to inflict suffering and destruction on the more-than-human world. Trying to explore and interpret this ideology has become the animating force behind my current research on the history of the Chihuahuan Desert, and has helped me understand why the environmental crisis today is so severe, why the response has been so unsatisfying, and what produced the condition of environmental amnesia in the first place. I have come to realize that, if given the choice, many people would not subscribe to these principles or behave accordingly. But the built environment often makes it impossible to opt out or even conceive of meaningful alternatives.

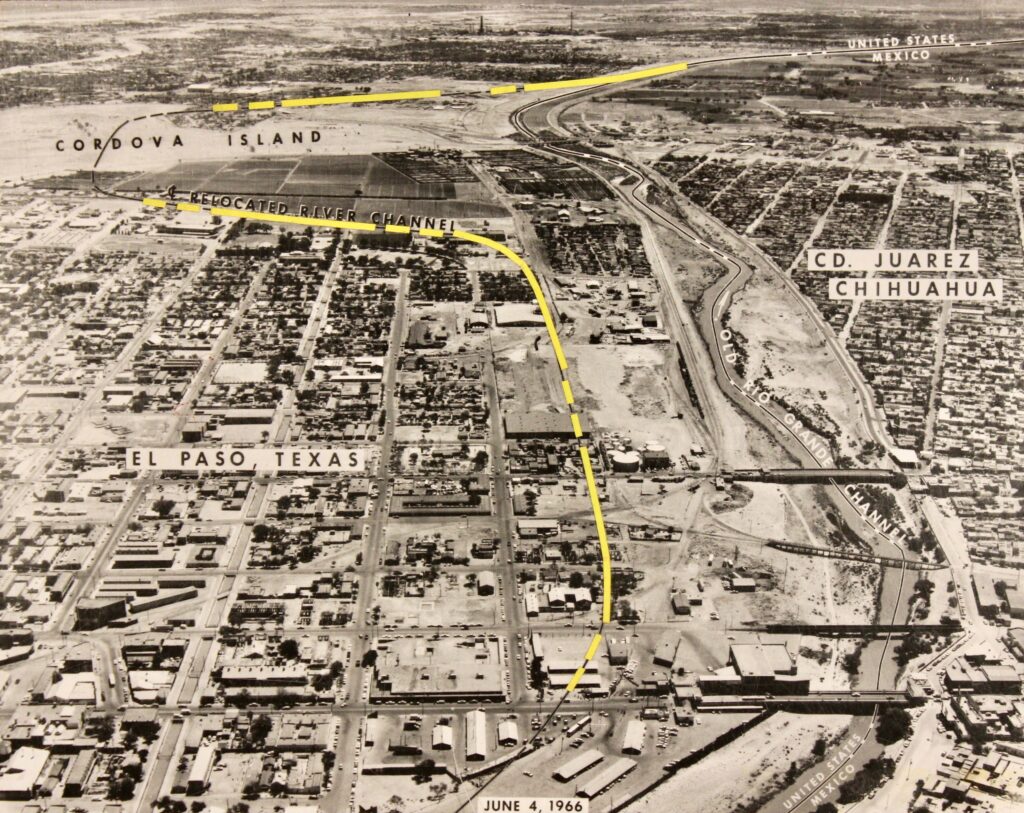

The Rio Grande is roughly 2,000 miles long, but not all of it doubles as a border. It begins in the high mountains of southern Colorado, flows down the entire length of New Mexico through an ancient rift, and only when it reaches El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, the upper edge of Latin America, does it begin doing double duty as the international divide. There, it also gets another name—the Río Bravo, as it is called in Mexico—an appellation just as out of sync with the conquered river of today as the Rio Grande. Not coincidentally, there is no place along its entire length that is more thoroughly destroyed as the section that passes between El Paso and Juárez. For this reason, that part of the river is a prime location to examine the twin problems of human supremacy and environmental amnesia.

In the spring of 2024, I gave the keynote lecture for World Water Week at the University of Texas at El Paso. I explained in detail all the ways the river had been damaged. The short version of that talk is this: In the 1930s, 124 bends were cut out of the river, a process the hydraulic engineers of the time called “rectification.” In the 1960s, the entire river between El Paso and Juárez was moved and entombed in concrete. By the 1990s, the nonprofit environmental advocacy group American Rivers said that the Rio Grande presented “the greatest human health threat of any river in America due to headwaters-to-mouth degradation and to pollution.” According to its report, one of the most toxic sections was the El Paso/Juárez section.

After my talk, several young people came up to me and told me they had never really thought about the Rio Grande as an actual river. I told them I knew what they meant; I was once in their shoes. Environmental amnesia makes it difficult to see the river as an integrated system sprawling across both U.S. and Mexican territory. Instead, we now see it mostly as a synonym for the political divide.

What is to be done? One possibility is to take steps that are anathema to the capitalist societies we live in. Some people refer to this as rewilding—restoring sick ecosystems, reintroducing animals on the verge of extinction to their former range, and even removing dams and re-bending rivers. This draws on principles of de-growth and is antithetical to notions of progress through engineering as well as to green techno-utopian “solutions” to the ecological crisis. There are already many small-scale examples of this throughout Mexico and the United States.

But the idea of rewilding the Rio Grande between El Paso and Juárez is preposterous. It would involve tearing out the concrete channel which was the result of a century of diplomatic arbitration. It would expose thousands of people to flooding and displace even more. It would cut deeply into the urban fabric of both cities to make way for wildlife corridors. And it would necessitate the removal of all border fences, meaning we would somehow have to accept a political border that moved around according to natural flows. None of this is going to happen anytime soon.

But there is another way of responding to environmental amnesia. It is simply to begin the process of remembering how the landscape used to be. Part of this involves archival research. Part of it involves going outside and learning how to move under your own power across the land. Part of it involves learning about plants and animals and geology in unfamiliar ways. This is a mindset, an attempt to reconsider the assumptions we hold about the rightful place of our species and to think, for perhaps the first time, about the interests of the more-than-human world.

Experimenting with this kind of thinking is often discouraged because it has no obvious policy implications. But my contention is this: If we cannot accurately assess the depth of environmental amnesia into which we have sunk, then any environmentalist “solutions” are bound to be superficial, tangential, misdiagnoses that will inevitably fail.

So much creativity, local knowledge, connection to place, and sense of meaning has already been extinguished—we need to nurture a sense of radical ecological alternatives. By all means, we do what we can in the policy realm to limit ecological destruction and reduce suffering for all sentient beings. But beyond that, there is something valuable in imagining a better world, even if it can never be reached. And, to me, there is also something liberating about extending the realm of compassion beyond our species alone, not only to other lifeforms, but to the river itself. ✹

C.J. Alvarez is an associate professor in the Department of Mexican American and Latina/o Studies. He is the author of Border Land, Border Water: A History of Construction on the US–Mexico Divide (2019).