Benson Acquisition News

By LAUREN PEÑA

DECIDING WHAT TO KEEP, what to let go, and how to care for the objects that tell the story of our lives—family keepsakes, handwritten letters, unfinished manuscripts—can be overwhelming for anyone. For someone whose life has crossed borders, both literally and figuratively, that task becomes even more complex. For Cristina Rivera Garza, a Pulitzer Prize–winning author whose life and work span Mexico and the United States, the act of archiving is deeply personal and profoundly political.

On April 14, 2025, the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection welcomed Rivera Garza to a full house for an evening of conversation and celebration marking the acquisition of her archive. The event was more than a literary gathering—it was a moment of reflection. The author spoke tenderly of her late father, who had quietly begun collecting the family’s history, and of her late sister Liliana, who had followed in his footsteps. The archive, she shared, is not only a repository of words, but a living tribute to those who shaped her voice.

Born in 1964 in Matamoros, Tamaulipas, Cristina Rivera Garza is one of Mexico’s most innovative and influential contemporary writers. She is a two-time winner of the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize for Literature and a fearless literary experimenter. As a professor at the University of Houston, she leads the only doctoral program in Spanish-language creative writing in the United States. Her work blends fiction, historical research, and poetic language to challenge dominant narratives and conventional storytelling.

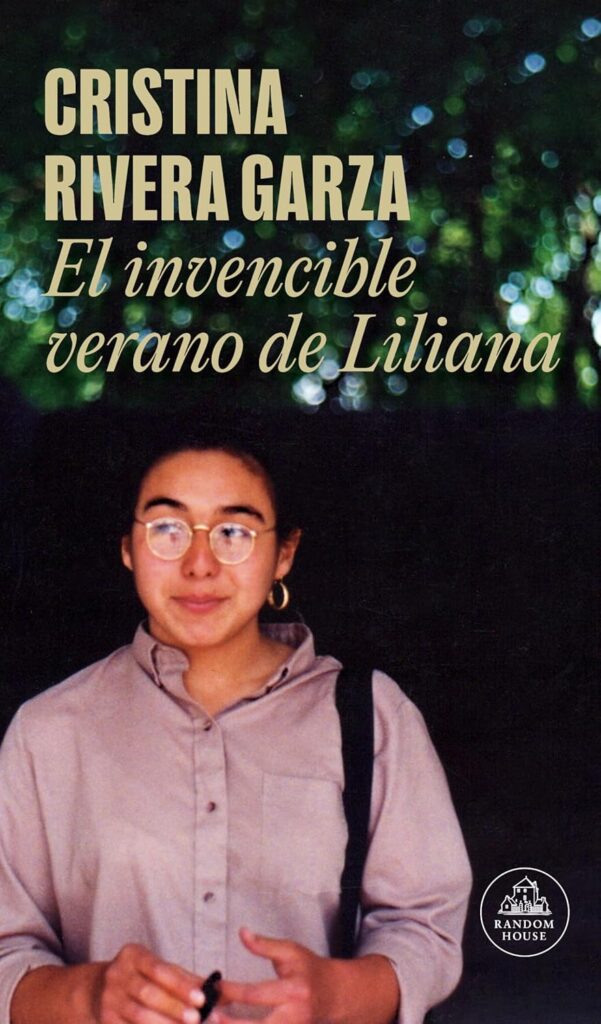

Her acclaimed novels and essays—including Nadie me verá llorar (1999), Dolerse: Textos desde un país herido (2011), El mal de la taiga (2012), and the memoir El invencible verano de Liliana (2021)—examine themes of gender violence, loss, and collective trauma. Through them, Rivera Garza gives voice to stories often erased from public memory. Growing up along the U.S.–Mexico border, she was shaped by the cultural and linguistic fluidity of that space. Her writing reflects this identity, informed by her studies in urban sociology at UNAM and a doctorate in Latin American history from the University of Houston. This academic foundation allows her to seamlessly interweave storytelling, scholarly inquiry, and poetic expression.

Rivera Garza’s novel Nadie me verá llorar exemplifies this approach. Set in La Castañeda, a psychiatric hospital in early-twentieth-century Mexico, it tells the tragic love story of Joaquín, a photographer and addict, and Matilda, a rebellious patient whose life defies social conventions. Yet the novel transcends this romantic premise. It has become a powerful meditation on how medical discourse and institutional power define sanity and madness in Mexico’s tempestuous historical past.

Language itself is a central theme in Rivera Garza’s work. She experiments with form, voice, and narrative structure, often incorporating archival fragments, poetic interludes, and literary citations. In works like Dolerse: Textos desde un país herido, La muerte me da, and El invencible verano de Liliana, the author uses language not only as a medium of expression, but as a tool of resistance. In El invencible verano de Liliana (2021, published in English as Liliana’s Invincible Summer in 2023), Cristina Rivera Garza pays tribute to her younger sister, who was murdered by an ex-boyfriend in the summer of 1990. She writes: “Aquí falleció mi hermana. Me corrijo: aquí la asesinaron. Según la orden de arresto: aquí la mató él” (33).1 The deliberate act of self-correction—from the softened falleció to the stark and accurate asesinaron—illustrates her refusal to obscure violence through euphemism. This linguistic shift is not simply a matter of word choice; it is a powerful act of protest. By naming the act for what it is—murder—she challenges the social and legal language that so often diminishes or erases the brutality of femicide. The subsequent clarification of agency—“la mató él”—further asserts accountability, breaking through the passive constructions that typically distance perpetrators from their crimes.

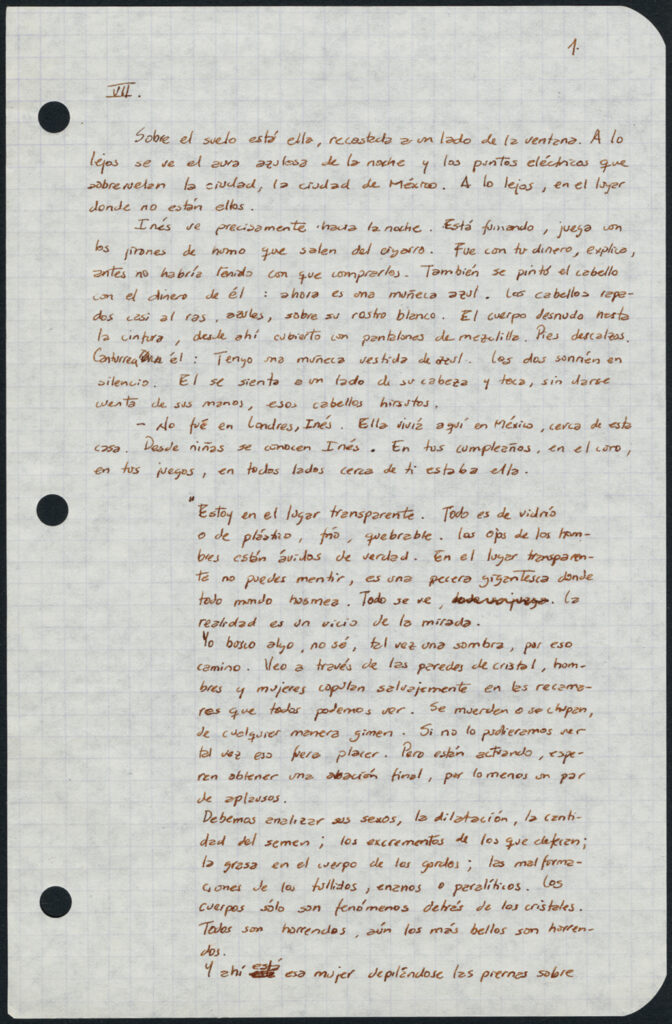

Written decades after Liliana’s murder, the text functions as both an act of remembrance and a form of literary justice. Through its narrative, Rivera Garza reconstructs Liliana’s life and the circumstances surrounding her death by using her sister’s personal writings, diary entries, letters, and official documents. In prose that encapsulates the intimacy of sisterhood, she deploys precise language that condemns the systemic impunity and gender-based violence that persists in Mexico.

Ante lo inconcebible, no supimos qué hacer. Y callamos. Y te arropamos en nuestro silencio, resignados ante la impunidad, ante la corrupción, ante la falta de justicia. . . . Y, mientras eso pasaba, mientras nos arrastrábamos por debajo de las sombras de los días, se multiplicaron las muertas, se cernió sobre todo México la sangre de tantas, los sueños y las células de tantas, sus risas, sus dientes, y los asesinos continuaron huyendo, prófugos de leyes que no existían y de cárceles que eran para todos excepto para ellos, que contaron desde siempre con el beneplácito de la duda y la disculpa anticipada, con el apoyo de los que culpan sin empacho a la víctima. (43)2

Here, Rivera Garza mourns as she bears witness. The cadence of her prose mirrors the weight of silence, shame, and systemic failure. The plural voice in “no supimos qué hacer” emphasizes the paralysis of those left behind, forced to navigate a legal and cultural framework that offers neither justice nor closure, and plenty of victim-blaming. The multiplication of dead women (“se multiplicaron las muertas”) is not just a tragic statistic but a haunting reminder of how normalized femicide has become.

Her bodily and visceral imagery—“los sueños y las células de tantas, sus risas, sus dientes”—evokes the physical and emotional traces of lives cut short, and insists on their presence. She refuses to let them be reduced to numbers. Instead, she demands we see them, remember them, and feel the horror of their absence. By naming the impunity—“prófugos de leyes que no existían . . . con el beneplácito de la duda y la disculpa anticipada”—Rivera Garza lays bare the complicity of the state, of society, of discourse itself. This becomes an act of defiance against a narrative that excuses, erases, and perpetuates violence.

Preserving her sister’s voice through these writings is Rivera Garza’s ultimate act of protest. It refuses the erasure of victims and challenges the sterile language of legal reports, revealing the bureaucracy that often dehumanizes stories like Liliana’s. By capturing the complexity of mourning and the struggle for justice, Rivera Garza denounces a broader social epidemic while issuing a powerful call to remember, fight, and resist.

Through her bold, genre-defying body of work, Cristina Rivera Garza has reshaped the landscape of Latin American literature. Her writing follows in the footsteps of a constellation of authors such as María Luisa Puga, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Alicia Gaspar de Alba, whose archives also reside at the Benson. Together, they offer powerful insights into identity and the radical potential of storytelling. The Cristina Rivera Garza Papers at the Benson Latin American Collection include poetry, photographs, essays, personal correspondence, and manuscripts. Among the collection’s most moving treasures are letters between Cristina and her sister Liliana, along with Liliana’s personal diaries. The archive opens up a rare window into Rivera Garza’s creative process and intellectual world. It is not just a collection—it is a living legacy and a gift to future generations of readers, writers, and scholars. ✹

Lauren Peña, PhD, is Head of Collection Development at the Benson Latin American Collection.

Notes

- “Here . . . my sister passed away. I stand corrected. She was killed here. According to the arrest warrant, he killed her here.” From the English edition: Cristina Rivera Garza, Liliana’s Invincible Summer: A Sister’s Search for Justice (New York: Hogarth, 2024), 25.

- “Faced with the inconceivable, we did not know what to do. So we shut up. And we shrouded you in our silence, resigned to impunity, to corruption, to the lack of justice. . . . And while this unfolded, as we crawled under the shadows of the passing days, dead women multiplied in our midst. The blood of so many rained over Mexico. . . . The dreams and cells of so many, their laughter, their teeth: it all went away. And the murderers continued to flee, fugitives from laws that did not exist and prisons that were for everyone except them, they who had always enjoyed the benefit of the doubt, the anticipated apology, and the support of those who blame the victim without so much as a flinch.” Ibid., 36.