By ADELA PINEDA FRANCO

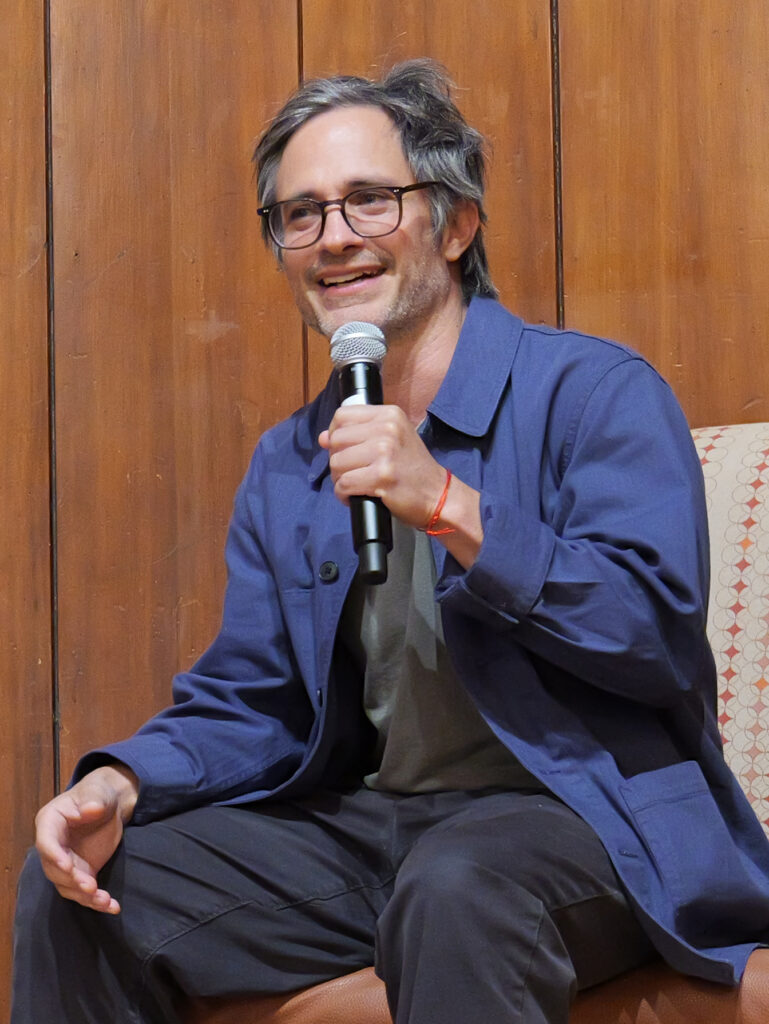

THIS YEAR, the Austin Lecture on Contemporary Mexico, a signature event of the LLILAS Mexico Center, was especially memorable. In celebration of both the 85th anniversary of LLILAS and the 45th anniversary of the Mexico Center, the lecture welcomed celebrated actor, director, and producer Gael García Bernal to the UT campus. I had the pleasure of being his interlocutor in a conversation guided by the notion of territory and its connection to cinema. The topic allowed us to rememorate his acting roles in iconic films. Yet, most importantly, we explored the way space, place, and history converge in the medium of film to reflect on our being in the world, and to critically understand the way emotions shape the everyday life of social and political reality.

García Bernal’s debut as an internationally acclaimed film actor coincided with the resurgence of Mexican cinema on the world stage at the turn of the millennium. Unlike the state-sponsored model that supported Mexico’s auteur films of the 1940s, the 1990s ushered in a more uncertain yet diversified system of film financing. A young generation of entrepreneurial filmmakers was to leave behind the international image of Mexico that the Golden Age (1933–1955) had promoted through the films of director Emilio Fernández and cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa, mainly those based on epic narratives of the Mexican Revolution or on Edenic landscapes of rural Mexico. They also distanced themselves from the urban mythologies of the Golden Age, where charming characters like Cantinflas (Mario Moreno) or Pepe “El Toro” (Pedro Infante) had helped make the drastic changes of modernization more bearable. Over the next decade, three such filmmakers—Alfonso Cuarón, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Guillermo del Toro—would achieve international acclaim in Hollywood.

By the late 1990s, new cinematic mythologies emerged, woven into narrative structures that also addressed the challenges of uneven modernization. However, the characters in these films were no heroes; they no longer inspired the same hope that economic hardship, social inequality, impunity, or corruption could be overcome through the redemptive resolutions of melodrama. The 1990s was a decade of free-market enthusiasm, aimed at promoting economic growth and Mexico’s commercial integration with the United States and Canada through a historic trade agreement. Yet such neoliberal measures failed to mitigate the economic recession rooted in the international debt crisis of the 1980s, and they did little to curb political instability and corruption. Instead, an Indigenous rebellion with major international appeal broke out in the southern state of Chia-pas, heralding the collapse of the one-party system that had ruled the country for many decades.

This was the backdrop for García Bernal’s debut at age 21 in the groundbreaking film Amores perros (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2000) as Octavio, an impulsive young man who enters his dog in brutal fights in hopes of earning enough money to run away with his brother’s wife. Set in Mexico City, the microcosm of a fragmented society shaped by the political and economic challenges outlined above, this box office success follows the lives of vastly different characters who become providentially intertwined by a car accident and the resilience of a dog named Cofi. Amores perros, written by Guillermo Arriaga and photographed by Emmanuel Lubezki, brought to the fore the insurmountable distance between social classes, the loss of hope in revolutionary transformation, and a growing disillusionment with entrepreneurialism as an existential path to happiness. The film called for a reassessment of family values, yet, through characters who were all too human in their cynicism, mischievousness, and incestuous impulses. García Bernal’s burning eyes, accelerated pulse, trembling hands at the wheel would remain etched in the memory of cinemagoers for years to come, propelling him onto the world stage as a first-class actor.

The notion of territory has shaped García Bernal’s professional career. It encompasses Mexico City, the chaotic expanse of Amores perros, a collage of juxtaposed shots captured with a frantic roving camera, but also extends to the long stretch forming the Mexican republic in Y tu mamá también (Alfonso Cuarón, 2001), a road movie that explores the sexual awakening of two adolescents (played by García Bernal and Diego Luna) who are forced to test the limits of their friendship not only due to their mutual attraction to a beautiful older (yet secretly ill) woman, but because of the class differences between them. The apparently mundane plot unravels against the backdrop of “the other” Mexico, quietly captured by a discreet camera: the Mexico of domestic workers, peasants, and fishermen, stripped of romanticized portrayals. During our conversation, García Bernal recalled the culture of camaraderie that a young Cuarón promoted among his crew during the shooting of this minimalist film, outside the constraints of large studios. This environment allowed Gael to develop his best acting qualities, namely, his ability to project difficult emotions, including vulnerability. “He’s like Al Pacino or Dustin Hoffman,” Cuarón said once, referring to Gael’s physical height as an inverted metaphor for his talent, “the kind of actor whose aura and energy make you think they’re huge.”

The idea of territory also resonates with the thick layers of social experience that surround not only the enduring hope called Latin America in The Motorcycle Diaries (Walter Salles, 2004), a biopic of young Che Guevara, but also with the legacy of colonialism in También la lluvia (Icíar Bollaín, 2011), a film about a film on the Spanish Conquest. In The Motorcycle Diaries, García Bernal plays the upper-class medical student turned revolutionary after traversing the vast South American territory and confronting its open wounds, most powerfully condensed in the image of the suffering yet resilient patients of a leprosarium. In También la lluvia, he plays the auteur of a cinematic epic about the Conquest, whose artistic dream is shattered by an overwhelming social reality. These two films, along with many others, particularly No, directed by Chilean filmmaker Pablo Larraín, attest to García Bernal’s versatility as an actor.

The territory of the U.S.–Mexico border is another space that has inspired him to deepen his craft, as seen in films like Cassandro (Roger Ross William, 2023) and the lesser-known The King (James Marsh, 2005), his English-language debut. In both films, García Bernal plays a Mexican American character: the charismatic gay wrestler in Cassandro, and the vengeful illegitimate son of an Anglo-American Protestant pastor in The King. A truly skilled actor, Gael García Bernal is capable of traversing geographical, linguistic, and cultural borders. In the end, acting is the art of becoming someone else in order to critically rediscover society.

As a producer, García Bernal has collaborated with Diego Luna and others to establish Canana Films and, more recently, La Corriente del Golfo, ventures through which he has promoted a multi-faceted notion of territory, creating a growing space for critical filmmaking. His thoughts reminded me of Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s views on film as a vehicle to convey both emotions and ideas. The Cuban filmmaker once wrote that emotion and intellect must coexist in film to produce a liberating force, one that remains deeply enmeshed in the very reality that gave birth to cinema. ✹

Adela Pineda Franco is director of LLILAS and Lozano Long Endowed Professor in Latin American Literary and Cultural Studies.

References

“Gael García Bernal: The pandemic has taught me that I need something to say.” Interviewed by Ryan Gilbey. The Guardian, May 1, 2020. Available at theguardian.com/film/2020/may/01/gael-garcia-bernal-the-pandemic-has-taught-me-that-i-need-something-to-say

Gutiérrez Alea, Tomás. “The Viewer’s Dialectic.” Trans. Julia Lesage. Jump Cut 29 (February 1984): 18–21. Available at ejumpcut.org/

archive/onlinessays/JC29folder/ViewersDialec1.html

Monsiváis, Carlos, “Mythologies.” In Mexican Cinema. Ed. Paulo Antonio Paranguá. Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes (Mexico) / British Film Institute, 1995.

Sánchez Prado, Ignacio. Screening Neoliberalism: Transforming Mexican Cinema, 1988–2012. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2014.

Tierney, Dolores. New Transnationalisms in Contemporary Latin American Cinemas. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.