By ALBERT A. PALACIOS and ANA A. RICO

This exhibit traces the many revolutions Mexico experienced between 1910 and 1916 to free itself from authoritarianism. The exhibit was created and formatted for travel, and opened in early June at the University of Texas at El Paso. It will travel to the El Paso and Austin public libraries this fall.

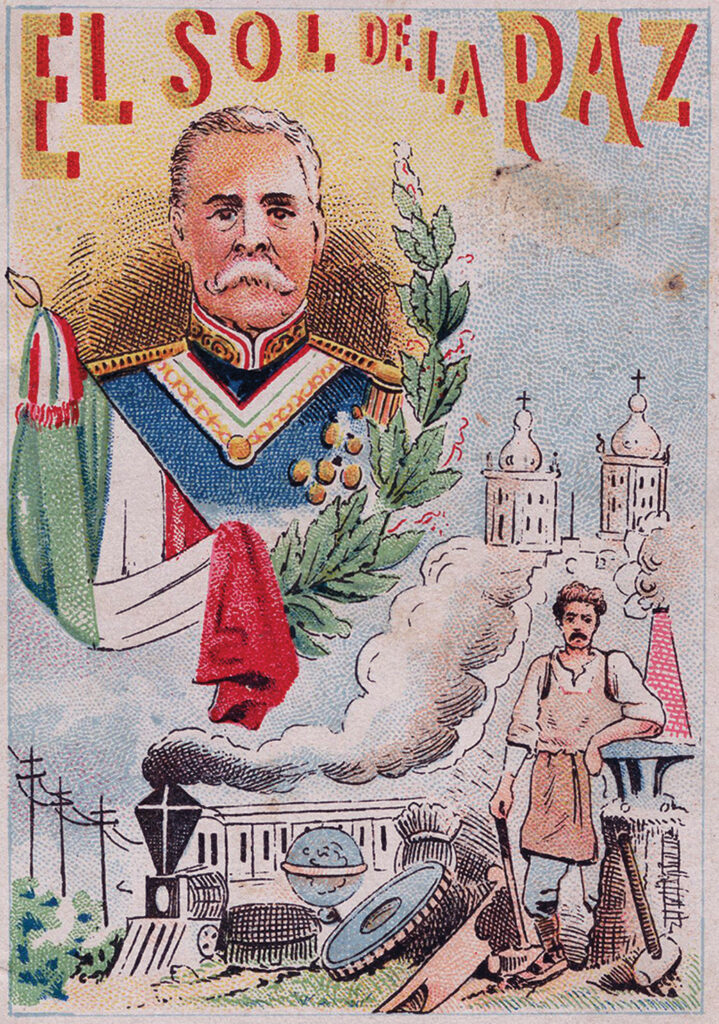

El Porfiriato

Mexicans have a long history of fighting for democracy. Throughout the nineteenth century, they broke free from a king, two emperors, and a general to obtain and maintain a democratic federal republic. Unfortunately, as the century closed, Mexicans ended up where they started the 1800s—under the rule of another strongman, General Porfirio Díaz. However, history showed that they would not endure tyranny for too long in the twentieth century.

After years of political turmoil, the stability Porfirio Díaz established from 1876 onward allowed him to maintain a dictatorship. During his decades-long rule, he transformed Mexico’s economy through international investment, which primarily exported the country’s resources to the U.S. and Europe. To facilitate this extraction, Díaz used government and foreign funds to build Mexico’s railroad and communication infrastructure.

On the Eve of the Centennial

As the eve of its centennial approached, Mexico was in political turmoil. During the 1910 elections, Francisco I. Madero, a northern elite, led a popular anti-reelection movement against dictator Porfirio Díaz. Sensing an impending defeat, the Porfirian machine stifled the opposition, jailed Madero, and “re-elected” Díaz in June 1910, just in time to prepare for Mexico’s centennial celebrations.

At right and below, official photographs of Mexico’s September 1910 centennial celebrations.

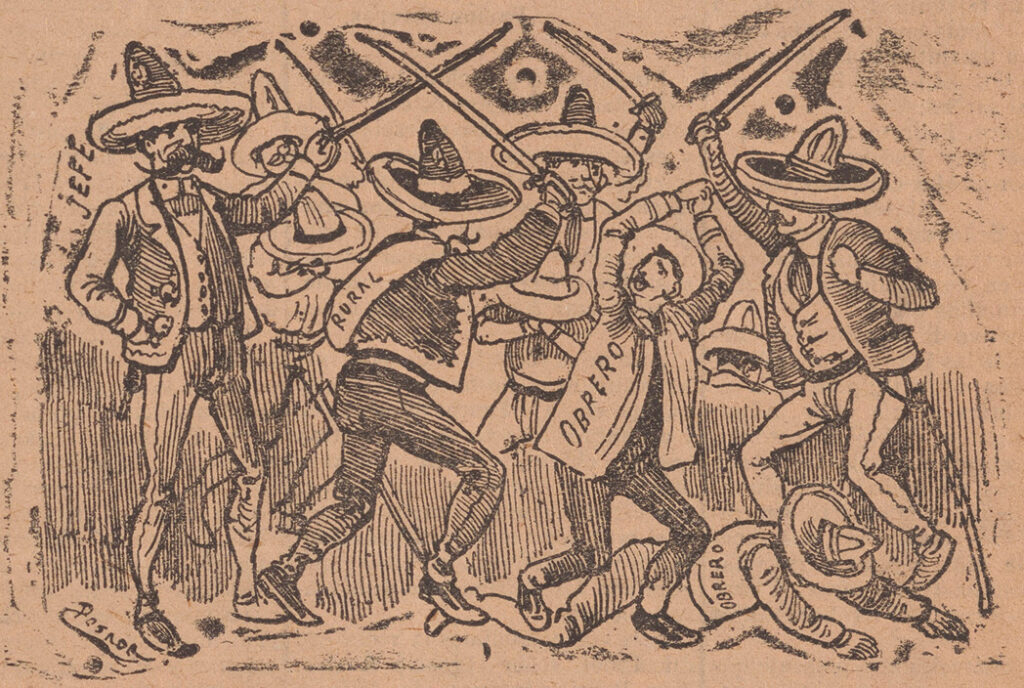

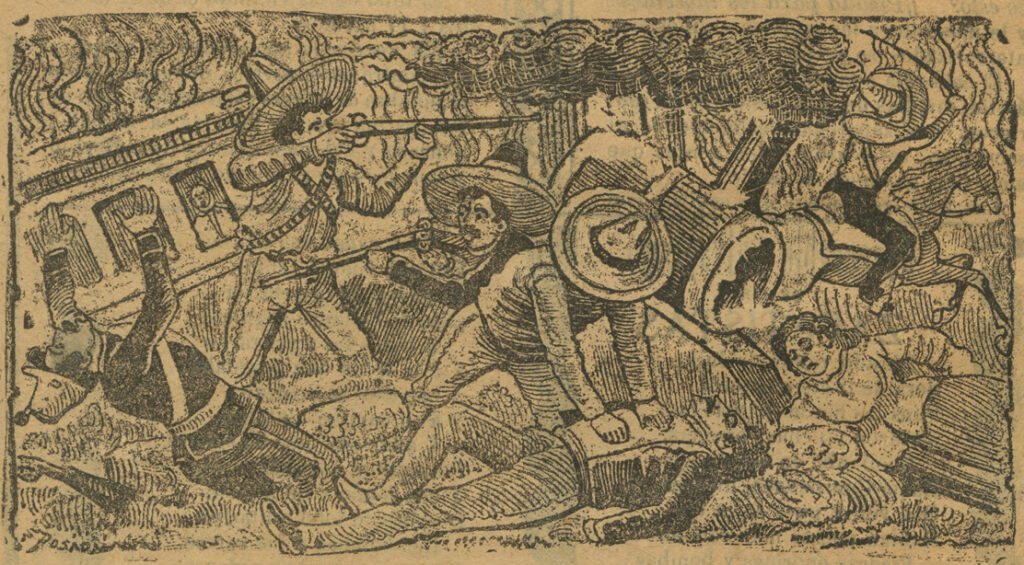

Revolution Erupts

Madero, from Texas, called for rebellion in October 1910, and Mexicans throughout the country answered. Fighters in the north included guerrillas led by Pascual Orozco and Francisco “Pancho” Villa, commanded by Madero beginning in February 1911. The following March, Emiliano Zapata and his agrarian soldiers revolted in central Mexico.

Women in the Fight

Soldaderas, or women soldiers, were a significant part of revolutionary forces. Some leaders acknowledged their importance to the movement. Emiliano Zapata famously made women, such as ex-Madero journalist Juana Gutiérrez, his colonels. Others, like Pancho Villa, considered them a burden at the barracks and on the battlefield. Although many did not receive recognition, it does not take away from the impact they had on the revolution.

Ten Tragic Days and U.S. Intervention

Longing for the Porfirian past, Mexico’s conservative elite and military pushed back in 1913. In a period that would come to be known as the Ten Tragic Days—la Decena Trágica—three army generals led a coup against President Francisco Madero and Vice President José María Pino Suárez, leading to their imprisonment and assassination at the hands of General Victoriano Huerta, formerly a Madero loyalist. Huerta assumed the presidency, and, refusing to support Díaz’s candidacy in the October elections, became Mexico’s next dictator.

Photographs show the U.S. invasion, destruction, and imprisonment of Mexicans in Veracruz.

Woodrow Wilson did not recognize Huerta as Mexico’s legitimate president. In an attempt to undermine “the usurper,” he authorized the invasion of Veracruz on April 12, 1914, to block Huerta’s importation of firearms. The U.S. occupied the port until November.

Revolutionary Borderlands

Huerta’s coup, which most Mexicans did not support, and his authoritarianism revitalized the revolution. While he encountered rebellions throughout the country, the northern states posed the greatest threat. After Huerta murdered Chihuahua’s governor, a coordinated insurgency started growing in Coahuila, Chihuahua, and Sonora. The region’s access to U.S. supplies, and to a railway system to transport them across the area, made the borderlands a revolutionary haven.

Pancho Villa joined the rebellion in 1910. As the leader of Chihuahua’s rebels, he began to command the North Division, the largest revolutionary force, in 1913, taking advantage of the Ciudad Juárez–El Paso link to supply it. His leadership would become infamous, controversial, and inextricably linked to the border.

Venustiano Carranza, governor of Coahuila, and General Álvaro Obregón commanded the Sonoran offensive. Rebels across northern Mexico joined their effort after Carranza called for the removal of “the usurper” Huerta and the reinstatement of constitutional rule in March 1913. Railroads and U.S. firearms soon made the “Constitutionalist” army a formidable force against Huerta’s army.

From Democracy to Reform

Carranza, Obregón, and Villa coordinated their northern forces with Zapata’s central militia to confront Huerta in the spring of 1914. Acknowledging defeat, Huerta resigned and fled Mexico on July 17, 1914. The revolutionaries held a convention in October 1914 to determine next steps. They agreed on prioritizing land and labor reform over democracy, but their loose alliance fell apart as ideological differences and personal ambitions surfaced. Starting in 1915, Carrancistas battled the Villista-Zapatista bloc for power until July, when Obregón handed Carranza the victory. Despite this defeat, Villa and Zapata continued to fight through 1916.

Like Díaz, Madero, and Huerta, Carranza used force to suppress dissent. He abolished the federal army, closed the courts, and suspended constitutional rights. Once he became provisional president, his government controlled the press and sidelined opposing revolutionaries in local and state leadership.

Carranza convened his supporters in November 1916 to create a constitution, which codified labor and land reform. Although he won a presidential election in March 1917, his government soon splintered, with some factions refusing to fall in line. This enabled sidelined revolutionaries and the working class to gain influence with votes until they eventually placed their own representatives in Mexico’s new democratic government. ✹

The reproductions shown here are from the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, The University of Texas at Austin. The traveling exhibition was organized by Dr. Albert A. Palacios and Ana A. Rico, designed by Jennifer

Mailloux, and financed by the U.S. Department of Education. To see the full exhibition, interactive maps, and other educational resources, please visit Mexico’s Fight for Democracy.

Dr. Albert A. Palacios is LLILAS Benson Digital Scholarship Coordinator.

Ana A. Rico is Resident Librarian at the Benson Collection.