In Arabic literature studies, realism is taken for granted as the natural apogee of modern narrative fiction and a point of departure for “postmodern” narrative production. Realism is enshrined, in both Europe and the Arab world, as the canonical foundation of all literary modernities.

When Arab critics use the word “reality” to talk about Arabic fiction, they mean “national reality,” a term that raises the specter of a whole set of specific historical and social issues such as colonialism and the anti-colonial struggle, the rise and hegemony of national bourgeousies as well as the real and imagined social composition of the national community.

By examining the critical reception of the series of late nineteenth and early twentieth century Arabic texts that constitute what I will call, “illegitimate fictions”, we can better understand the ways in which genre is appropriated and constructed as a hegemonic cultural discourse at a given historical moment

The problems of genre and ideology in arabic fiction

Popular oral storytelling seen as corrupting and deceptive as opposed to the truth of fiction

Narration became the process through which the problem of the individual confronting society in an adversarial relationship was negotiated, managed, resolved.

In its efforts to forge its own destiny, this autonomous self is made to contain and resolve the existential contradiction produced by the new social order, thus emerging as a kind of “mirror” of the social body as a whole.

Tim brennan – the novel shows the one, yet many and allows people to imagine one community as the nation. (Why nation and not class, who worked to try to create this new belonging)

Novels inextricably bound to the linked ideologies of nationalism and romantic individualism as they emerged in Egypt roughly around the time of the First World War and the 1919 revolution

in Egypt, the “artistic” novel emerges at the point when a properly nationalist bourgeois intelligentsia begins self-consciously to articulate its role as a powerful and exclusive political and cultural vanguard.

Is the anxiety over the marxist novel due to the fact that the novel is a machine for bourgeois subjectivity?

Ideology is in effect the culture’s form of writing a novel about itself for itself. And the novel is a form that incorporates that cultural fiction into a particular story. Likewise, fiction becomes, in turn, one of the ways in which the culture teaches itself about itself, and thus novels become agents of inculcating ideology. (Lennard Davis, 1987, 24–25)

How would this limit the ability to depict multiple forms and complex class interactions

thick description” of locations that Muhammad Khayrat found so tedious in European novels was intended to inscribe the all- important nuances of class hierarchies and the social relationships between ownership, social power and moral character that developed in eighteenth and nineteenth century Europe.

Novelistic subjectivity—the minute charting of an individual self’s interior moral and psychological landscape—was the necessary narrative medium through which contempo- rary bourgeois ideology was refracted, negotiated and disseminated

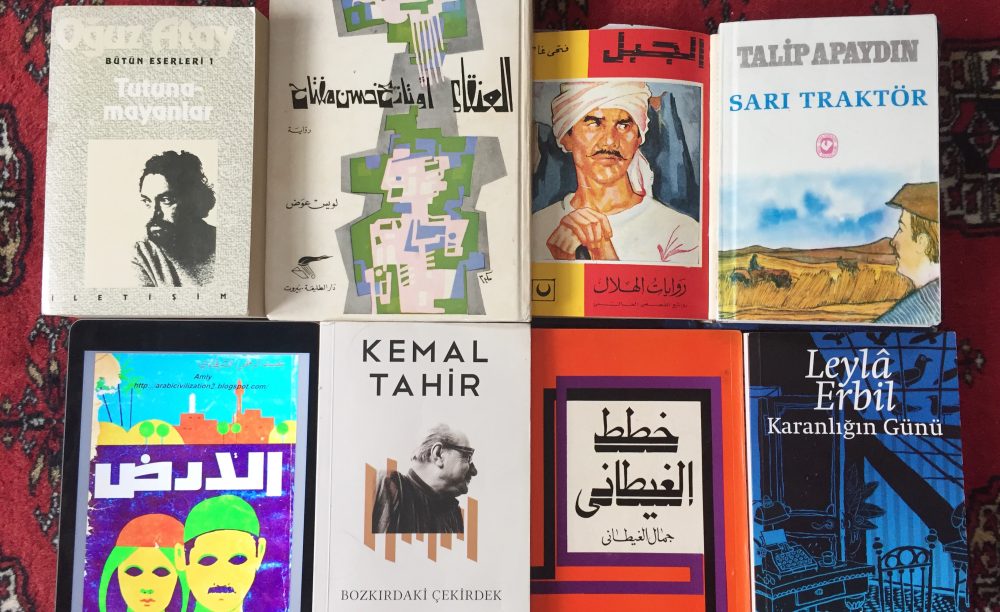

This completely explains why tutunamayanlar is tryingto break out of the novel form, by being so uncomfortable with novelistic-bourgeois subjectivity

Jabir ‘Asfur suggests that the intelligentsia of this new bourgeoisie appropriated the novel genre as a way of challenging and dismantling the old Ottoman and Arabic social and literary hierarchies. If classical poetry was the proper genre of the courtly aristocracy and the folk tale or epic that of the popular classes, then the novel was the perfect literary vehicle by which the emergent nationalist middle-classes could assert their dominance on the cultural stage

Who has claimed that the novel is irredeemably bourgeois?

from simply being a neutral and/ or “maturing” mimetic strategy of representation—as implied in ‘Ubayd’s idea of “the dossier”, as well as by developmentalist critical discourse—realism in Nahdawi fiction encoded a specific social ideology, a specific set of social attitudes towards class, gender and culture as they were in the process of being instituted

Husayn here clearly understands the representational mechanics of the new fiction as, above all else, a strategic craft that involves a hierarchical and disciplinary relationship between a middle- class national elite, and the rest of society—particularly its “base” classes. It is this kind of understanding of the politics of representation within a particular social context that Arabic novel studies have neglected to take into account when describing and cataloguing the history of the genre.

It was not until the period of social and political upheaval of the second half of the twentieth century in the Arab world that the representational politics of narrative realism were interrogated and radically rearticulated by a new generation of social realist and neo-realist writers.

It should be noted here that the iconoclastic social realist critics that emerged in the early 1950s (such as Mahmud Amin al-‘Alim in Egypt and Husayn Muruwwa in Lebanon) certainly did both question and elaborate on the representational politics of realism. However, they were mostly interested in the content of realist narrative rather than its semiotic and structural mechanisms