Tentative New Chapter Outlines

- The history of language ideology in modern Egyptian and Turkish literature

- language policy and politics in the post-war period

- The sociolinguistic landscape of Turkey and Egypt

- Language ideology and normative grammar

- Literature and metalinguistic awareness

2. Ideological Stylistics: Orhan Kemal and Kemal Yaşar find a voice

- Introduction with work from Orhan Kemal in prison developing style

- Considerations of language ideology play central role in the stylistic development of novelistic language

- The need to iconize certain registers as mimetic and develop sociolinguistically “neutral” register of narration

- Generic conventions help to reinforce this illusion (i.e. dialogue and the assumed stance of the narrative voice)

- Searching for elevated literary register in the 20th century

- There is a need for distinction because of language ideology and metalinguistic awareness, moving from Corneille to Flaubert means finding a language register that addresses “nobody in particular”

- How to adapt the language to address modern reading audiences

- Sabry Hafez on the use of the short story to train readers and the reading public and the change in artistic sensibility

- Class dynamics and appeals to populism

- Salama Musa

- Developing post-Ottoman literary stylistics

- Register stripping in Turkish to get rid of Ottoman stigma

- Ahmet Midhat critiquing the decadence of servet-i funun

- Trying to build language ideology appropriate stylistics in early Republican literature (AYCAN, Gizem A.)

- Looking for linguistic authenticity

- The “challenge” of Ammiya

- The village novel and the presence of vernacular speech

- Debates about addressing ammiya, realism is what heightens the question of ammiya to metalinguistic awareness

- Fusha as the only register which can express the full range of thought

- Lack of narrative voice in vernacular

- Populism and the search for Anatolian speech

- Search for folklore, dialects, obscure lexicon

- The “challenge” of a national language rather than accepting heterogeneity, conflating normative and imminent language

- Anxiety about the stifled national register and plenitude of vernacular speech, expressing the full range of thought

- Lack of narrative in vernacular, folklorism always mediated

- The “challenge” of Ammiya

- Dialogue becomes the compromise, able to preserve the narrative stylistics while attending to the particularities of time and place specific speech

- Look at Orhan Kemal’s strategies

- Look at Yusuf Idris’ strategies

- A form of realism with standard language ideology intact

- The shortcomings of realism and imminent language

- Direct discourse fallacy

- The narrative voice as a voice from nowhere (not a problem in film because there is usually not a diegetic voice, nor in poetry because there is no attempt at mimesis)

- The novel form as trying to separate out the imaginary and the fictiona3

- The language of ideology and the ideology of language

- The history of leftist discourse over “reaching the masses” as a form of metalinguistic anxiety

- The Roman à thèse, political slogans and Lecercle, and a sociolinguistic account of how political beliefs actually circulate (i.e. the indexical order)

- petit bourgeois anxiety on the failure to build class consciousness, the assumption that the use of slogans and political rhetoric is a top-down process of ideological persuasion

- Close reading of the Phoenix by Louis Awad and One Day All Alone by Tarık Buğra as example, or al-fallah

- Lost in normative grammar

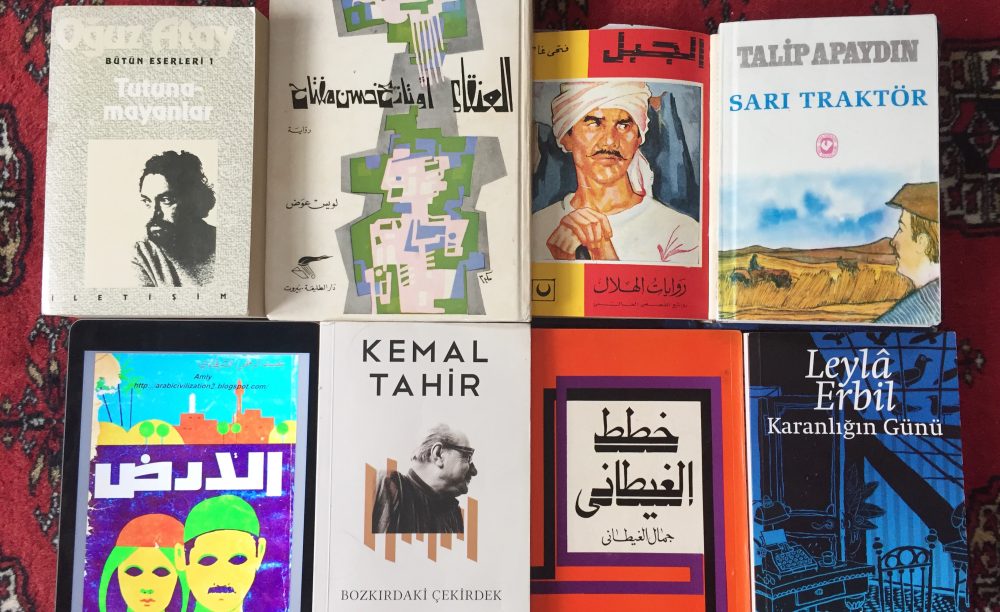

- Certain famous intertextual novels like Tutunamayanlar and the Plans of al-Ghitani rebel against the perceived strictures of monoglossic language by, ironically, resorting to those same language practices which generate monoglossic language: in Arabic by going back to historical forms of Fusha that were themselves a performative use of normative grammar (i.e. Gamal Ghitani recreating Ibn Iyas’s register of Arabic), and in Turkish through language play and invention that relies on the same methodologies as the Kemalist reforms (i.e. Atay’s playful use of Öztürkçe and reenactment of combing through historical sources for answers)

- Reacting to state censorship and lexical politicization (left/right) through a certain type of metalinguistic awareness (i.e. by focusing efforts on normative grammar)

- searching for the real (the cause of Selim’s suicide, a topography of al-khitat) in artificial language and getting nowhere.

- 1980s shift in language hegemony and rise of the marketplace of imminent grammars.