On July 20th, 1969, the world stopped.

While the Earth kept spinning, people from around the globe froze, captivated by the black and white footage of a man taking one small step onto another world. Following Neil Armstrong’s famous journey for all humankind, 11 more men touched down upon the surface of the Moon, ending with Gene Cernan in 1971, who boldly promised, “we leave as we came and, god willing, as we shall return.” However, in the 50 years since, Cernan’s proclamation has slipped from promise, to prophecy, to far off dream.

The greatest barrier keeping humankind from the Moon isn’t technology, but politics.

The Apollo missions were driven by the Cold War politics of the US and USSR battling for supremacy across every frontier. Conquering space was the holy grail of challenges that would prove to the world which regime was better, but the space race that followed scared the world as much as it did inspire. The United Nations enacted the Outer Space Treaty (OTS) in 1967 to ensure that the ongoing space race would be done “for peaceful purposes” to protect the province of all mankind. The OTS was a broad set of principles, little more than a framework, to guide the development of more detailed international laws, but other than a few small resolutions, it remains the primary legal structure for all international activity in space. The imprecise nature of the Outer Space Treaty has created immense problems for the international community as nations disagree on how the resources of space should be allocated.

The US seeks to return to the Moon, not for humankind, but for itself and its eight partners.

In 2017, the United States declared that it would return to the Moon under the Artemis Program and bring with it a new framework for operating in space. The Artemis Accords, bilateral agreements between the United States and eight other countries, would operationalize the loose framework of the OTS and allow for greater security and prosperity of all nations involved. Notably, the Artemis Accords eschewed traditional forms of international space law like the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPOUS) for a faster and more controllable system. This nationalistic approach has angered many dominant space-faring nations¬ – Russia, China, ESA, and others – who see this as a tactic by the US to dominate the new space era. Beyond its formation, the Artemis Accords are contentious in how they divide the resources of space amongst nations.

The most contentious part of the Artemis Accords is a fight over Moon rocks.

Much of the Artemis Accords is an extrapolation of the principles outlined in the Outer Space Treaty as an assuagement to other nations that the US isn’t trying to control space. The Accords have ten driving principles around transparency, interoperability, and the sustainability in space, but the two last principles have deterred many international partners. Specifically, these principles allow for the mining of space resources and the institution of safety zones around each nation’s operation. The exploitation of space resources directly conflicts with excerpts from the Moon Agreement – a UN attempt to expand upon the Outer Space Treaty in 1979 – that claims the resources of celestial bodies belong to all nations. While the United States and many other countries never ratified the Moon Agreement, the direct conflict between the Artemis Accords and the United Nations’ treaty highlight the contentious US decisions to pursue bilateral rather than international agreements. Furthermore, other nations have expressed major concern that safety zones are a pseudo claim of sovereignty over part of a celestial body, which is strictly outlawed by the Outer Space Treaty.

How then to revise the Artemis Accords to realign with Gene Cernan’s promise?

If the United States seeks to return to the Moon for the benefit of all humankind, then it must make a commitment to adhering to international law. While the Artemis Accords were designed to operate faster than the tedious process of passing international treaties, the US should commit to a date in which it uses the lessons learned from Artemis to design an international treaty. Furthermore, the United States should ensure that no one nation can exploit all of a space resource by delegating power to an international committee that determines resource caps and specific areas of operation, rather than a first come, first serve basis.

With these revisions in mind, the United States can assuage fears of hegemonic control and refocus on the true mission of the Artemis Program: advancing the agency of humanity, one giant leap at a time.

Uncategorized

When Carbon-neutral Is Not Environmentally Friendly

Photo: PSNH / Flickr / Creative Commons

Carbon-neutral has become a buzzword that often conjures images of clean energy and a greener planet. Recently China has pledged to be carbon-neutral by 2060, and Japan aims to do the same by 2050. However, when a buzzword such as this proliferates, it becomes important to scrutinize its usage and inquire into its true meaning.

Theoretically, an activity is carbon-neutral if the amount of carbon emitted into the atmosphere equals the amount of carbon taken out of the atmosphere. However, in practice, it is not always that straightforward. The rates at which carbon is put into the atmosphere and taken out of it are important in determining if an activity is truly carbon neutral.

Energy generated from biomass, or plant material, is one example of an activity that appears to be carbon neutral, but may not be in practice. Biomass is often burned in the form of wood pellets, made from trees, manufactured for energy generation. Theoretically, a wood pellet manufacturer could plant one tree for each tree they cut down to make into wood pellets. In practice, though, the process is more complex. When the wood pellets are burned, the carbon they store will be released immediately into the atmosphere. However, the newly planted tree will take carbon out of the atmosphere slowly over its lifetime. Consequently, in the short term, burning biomass for energy will put more carbon into the atmosphere.

Regardless, the EPA designated all energy generated through biomass combustion as carbon neutral in 2018. This policy incentivizes investment in biomass generated energy because there are fewer regulations on carbon-neutral energy sources than those without a carbon-neutral designation. Because of these incentives, there is a risk that the policy will lead to an overall increase of carbon in the atmosphere, the opposite of its intended effect.

It is also important to consider that a carbon-neutral designation does not necessarily mean that an activity has a neutral impact on humans or the environment. Generating energy from biomass also poses risks to human health and biodiversity.

The process of burning biomass emits a variety of pollutants other than carbon. In fact, a biomass energy plant is dirtier than a coal plant. For each unit of electricity generated, a biomass plant emits 62% more nitrogen oxide, and 367% more particulate matter compared to a coal plant. These pollutants have harmful effects on the lungs and threaten the lives of people with preexisting conditions, like asthma.

Additionally, the creation of wood pellets for combustion degrades soil quality and reduces biodiversity. Wood pellets are often created from trees harvested from industrial lumber farms. The industrial planting and harvesting processes replace native forests, displace many species that rely on the forests, and strip the soil of nutrients.

Considering the risks that can arise when potentially harmful activities receive carbon neutral designations, we should carefully consider how and when we employ this term. It is even more important to be cautious when using carbon-neutral as a policy designation, which reduces the regulation of an industry. Carbon-neutral energy does not mean clean energy. We can produce more effective environmental policies by ensuring that activities we incentivize are beneficial for humans and the planet, rather than relying on theoretical claims of carbon neutrality.

Identity Crisis: US Digital Identity and Lagging Technology Leadership

The US government’s embrace of technology, even technology the government itself developed (see: ARPANET), often lags well behind its private-sector counterparts. Part of this is attributable to the glacial pace of large bureaucracy – but as more nations begin to embrace the internet as a weapon to be used in defense of government, the inadequacies of how slowly the US is embracing its own creation are laid bare.

I want to propose a digital identity policy framework that adapts the strategic elements of a strategy released by the Obama administration and integrates modern technology into the many functions of the US government. First, however, I want to briefly discuss the shortcomings of the past two administrations’ approaches to digital identity, then segue into how we might close the gap with governments around the world which are innovating more rapidly than in the US.

As a quick disclaimer, I am focusing this proposal on the federal government; many state, county, and municipal governments in the US have taken to the digital age with fervor and have actively begun implementing many of the same policies that I propose here. A few examples, that might lead to further research into how we might integrate the internet and digital technology into bureaucratic operations are the Wyoming state government’s work in cryptocurrency regulation and blockchain, the Kansas City government’s embrace of universal internet access and smart city innovations, and the San Diego government for its cybersecurity strategies.

One of the critical building blocks of this proposal is the National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace (NSTIC). The Obama administration’s strategy outlines a move toward more robust cyber infrastructure catered to individuals. The proposed strategy is broad and far-reaching (the administration cites eight principles to improve in their Identity Ecosystem: privacy protections, convenience, efficiency, ease-of-use, security, confidence, innovation, and choice) but contains few concrete programs that facilitate these goals. The strategy is effective, however, at communicating the pressing nature of digital identity programs and the need for greater protection of democracy, individual rights, and trust in the internet age.

Unfortunately, the policy was only revisited once, with a $3.7 million commitment in 2015, and has received little acknowledgement from the Trump administration for the past four years. In fact, the web page for the digital identity initiative, found on the NIST site, throws up an error message if you try to navigate for more information.

As such, I recommend we build on the NSTIC with a significant reinvestment in the program. An investment somewhere in the vicinity of $250 million would match similarly scaled private sector networks and would provide a significant basis for a digital program that could expand and improve the efficiency and efficacy of existing government programs, as I will show. This recommendation follows three phases: immediate, near-term, and long-term.

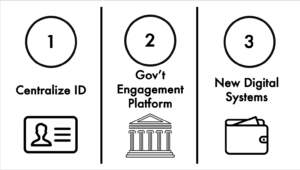

Step one – We centralize identification factors including government issued IDs, passports, and drivers’ licenses in a secure digital platform that encrypts user da

ta but allows instant access to forms of identification for all US citizens and residents.

Step two – We build out a platform and digital infrastructure to connect government assistance programs, taxation, and other services to those who are eligible – a process that has begun but is not well-known or widely-used. The programs this might benefit (including SNAP, the ACA, affordable housing assistance, Medicaid, and the CARES Act) are widely available, although often unwieldy and susceptible to fraud due to inadequate verification processes.

Step three – We begin work to integrate digital systems into new policy, including digital wallets, census counting, and voter registration.

This proposal will increase the US. government’s capacity for verifying the identity of citizens, decreasing the incidence and claims of fraud. It will also make the programs the US government implements more efficient in allocating funds and more effective at providing aid to individuals in need, potentially recouping the original investment if applied strategically. It will make our governance functions more accurate and targeted and will enable the potential expansion into other digital programs. And, an effective digital identity program might mark the reemergence of the United States as a leader and an innovator in cutting edge technologies and bureaucratic innovation.