On Thursday, October 23, at 7 p.m., novelist Jayne Anne Phillips reads from Quiet Dell, a novel based on the true story of a murderous West Virginia con man who preyed on widows, in a Harry Ransom Lecture. A reception and book signing follow.

Stephen King said of Quiet Dell: “In a brilliant fusion of fact and fiction, Jayne Anne Phillips has written the novel of the year. It’s the story of a 1931 serial killer’s crime and capture, yes, but it’s also a compulsively readable story of how one brave woman faces up to acts of terrible violence in order to create something good and strong in the aftermath. Quiet Dell will be compared to In Cold Blood, but Phillips offers soothing Capote could not: a heroine who lights up the dark places and gives us hope in our humanity.”

Phillips, whose papers reside at the Ransom Center, is the author of Lark and Termite, a National Book Award finalist. Known for her poetic prose and in-depth study of family dynamics, Phillips has received critical acclaim and major literary prizes, including a Guggenheim fellowship and two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Phillips is professor of English and director of the Master of Fine Arts program in Creative Writing at Rutgers University, Newark.

Below, Phillips discusses the inspiration behind her novel Quiet Dell, her archival research for the book, her writing process, and her own archive.

Your work often seems to draw upon your own family history for inspiration. The murders in Quiet Dell, for example, took place near your hometown in West Virginia. Can you talk about how history and family memory evolved into your novel?

My mother remembered holding her mother’s hand at age 6, walking along a crowded dirt road in the heat and dust of August—cars parked on either side as far as she could see—past a “murder garage” being taken apart piece-by-piece by souvenir-seeking crowds. Ever after, when we drove past the hamlet, ten miles or so from my hometown, she would point out “the road to Quiet Dell.” Thousands walked past the scene in the summer and fall of 1931, attracted almost as though to a religious site: an unimaginable slaughter of innocents. A con-man led a double life, found “wealthy” middle-aged widows through matrimonial agencies, and skillfully courted them in letters for months. He imprisoned and murdered an Illinois widow and her three children, 14, 12, and 9, and a Massachusetts divorcee, all of whom came to Quiet Dell willingly. The tragedy preoccupied a Depression-era nation, and the media spun it as a warning and lesson to women. The murderer was christened a modern Bluebeard, but the deeper story was far more complex. Quiet Dell is true to an evolving real event, but creates the world in which it happened, beginning the Christmas before the crime. I was interested in the children, in whom the novel finds “the angelic core of the dark world,” in creating lives for the women that reveal why they were vulnerable. For me, the tale began in 9-year-old Annabel Eicher’s voice at the magical turning of the year. Quiet Dell meets the history of a family that vanished with a counterpoint story in which that family is alive, and then alive in memory, directly influencing the lives of those who seek justice for them. The reader is endowed with a foreknowledge of event, but the fact of the event touches only the surface of its effects.

Can you tell us about the archival research you conducted with primary materials while writing Quiet Dell?

The actual names and facts of the crime seemed a Victorian fairy tale set in the ’30s: Sherriff Grimm, Judge Southern, Duty (the Eicher dog, “twice bereft,” whose photograph appeared in newspapers across the country), the Gore Hotel—and the fact that the trial took place on the stage of an Opera House before a towering backdrop of painted forest trees, left over from a previous production. The Clarksburg Harrison County Public Library allowed me to Xerox numerous pages of newsprint, and many pages of a haphazard “scrapbook” on the crime assembled by a 13-year-old boy, James Law (who grew up to own the most important bookstores in the area). I’ve always found photographs, particularly of strangers, to reveal whole dimensions of information, and I carried a small copy of the last known photo of the Eicher family in my wallet for years. Annabel’s gaze in that image, so wary and adult, suggested her character in the novel. As I was beginning my research, a family friend who knew I was writing about the Quiet Dell crime gave me an envelope he’d found in an antique dresser in Rock Cave, West Virginia. Across the front in faded pencil, it read, Piece of sound proof board used by Harry Powers during his notorious Murdering in the fall of 1931. I opened the envelope and held in my hand a thick felt square marked with a 3. As Rilke said, “Every angel is terrifying.” I came to know the woman who grew up in the Eicher home in Park Ridge, Illinois, and lives there today; the playhouse, and the mural Asta Eicher painted on the walls for her children, still exists. I gleaned hints from newspaper interviews with those who said they’d known Harry Powers under one alias or another; the statements were wildly contradictory. Not so the obituaries I was able to find online: the phrasing and tone implied specific narratives. I found the grandchildren of photographer Floyd E. Sayres through a hint in his obit; they allowed me to include his images of scenes associated with the crime, though the images are far more beautiful than the versions that appear in Quiet Dell. Letters from Powers and women who wrote to him appeared in newsprint; the trial transcript was a matter of record. These events took place nearly 85 years ago; the history was distant enough that I could use real names, yet invent the perceptions, thoughts, relationships, of the characters to tell my own “dark fairy tale.” The scant patterns of a real history, for me, cast a spell that is almost bewitching.

As a writer, how do you approach establishing a sense of place and time for your reader?

There is the Pound dictum, “No ideas but in things,” to guide the writer: specific physical fact infused with sensory detail. Words, in careful association, are sensual triggers for the reader; each reader brings a world of unconscious and subconscious memory to the text. Certain sense memories, smells, sounds, can connect us to pasts we did not experience. Readers have said to me, “When I read your work, I don’t feel as though I’m reading a story; I feel I’m inside the story.” Another said, of Termite (from Lark And Termite), “You make us want to be him.” Every art is a form of alchemy: transforming one element into another, widening, deepening, until one world connects to worlds before and beyond it. Literature is a crafted seduction in which the reader actively participates.

Can you tell us about your writing process? (For example, do you write on a laptop or desktop? Do you have an office or studio space dedicated to writing? Do you write during certain hours of the day? How do you go about revising your work?)

I began writing as a poet, and I continue to compose line by line, slowly, aware of the music and stress of the syllables in the lines. I write both by hand and on the computer (laptops and desktops, since I live in three cities), and print out every page, not only because I distrust machines, but because I revise on paper. I write in the daytime, never at night, in front of a window. I often work on longer projects in the summers, when I’m not engaged in my labor-intensive day job. Editing, teaching, discussing literature, advocating for talented students, is far too compelling.

Your archive is now open and accessible to researchers. What do you hope people will be able to learn from your papers and work?

Those spiral notebooks in which I composed my early stories seem to belong to another universe I once inhabited, while the archive of the present, boxes of more recent drafts, artifacts, lists, and correspondence, piles up around me. Access to an archive, not in a writer’s rooms but in a neutral, sacred space, the clean well-lighted place that is the Ransom Center, is a privilege, an intimate investigation. Touching actual pages, photographs, letters, comparing small and large changes from one draft to another, takes the reader inside the books, into the works themselves. It’s delicious.

You are the director of the Rutgers University- Newark MFA program. How does teaching influence your writing, and how do your experiences as a writer shape how you teach?

I don’t think teaching influences my writing, except to intensify the pressure of not writing—a tool I have always used, pre-dating teaching. Part of writing is the yearning toward what is still unseen and unknown. For me, ideas, rumination, research, are not the true thing; they only swirl around it. A book begins with language: a line of prose, a paragraph. The book is inside those words and the long struggle is to deepen and sustain what is genuine. I suppose I teach that one’s relationship to writing is as complex as one’s relationship to the self: it’s endless and mysterious, full of the mundane and the celestial in shifting quantities. No writer approaches words the same way; the “why,” unique as a fingerprint, is ineffable. The writer creates meaning where none is obvious, invents the dots and connects them. We’re like practitioners of the same unrecognized religion: the process itself is the experience. It’s witchcraft and soothsaying, and hard, grinding work.

What books are currently on your nightstand?

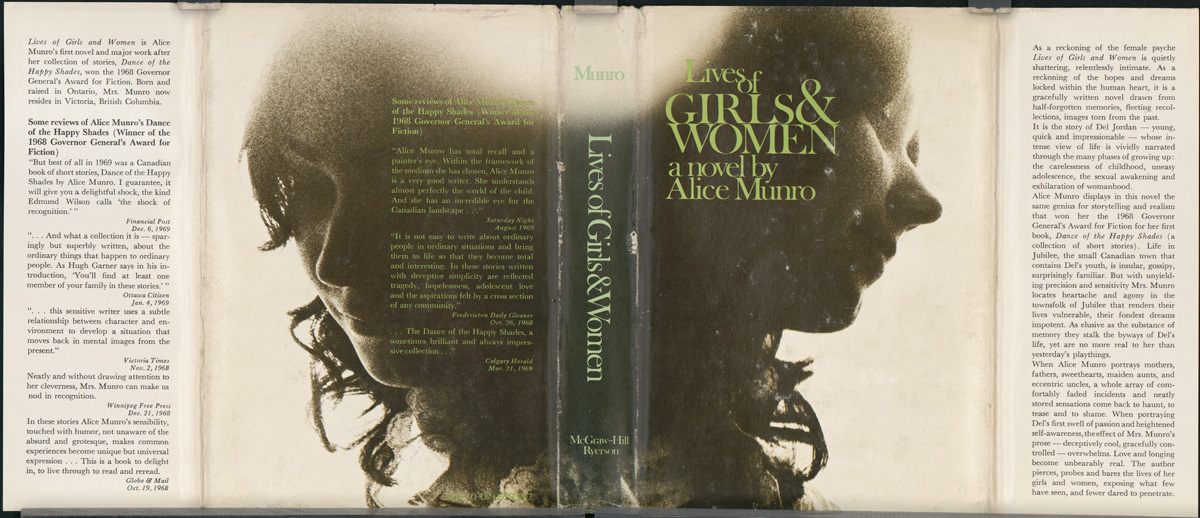

Fat City, by Leonard Gardner; The Beggar Maid, by Alice Munro; Mrs. Bridge, by Evan S. Connell (all books I’m teaching); a galley of Colm Toibin’s new Nora Webster; HER, a memoir by Christa Parravani, and Prelude To Bruise, just-published poems by Saaed Jones (these last two both recent graduates of RU-N MFA program).

Please click on thumbnails below to view full-size images.