“Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.”

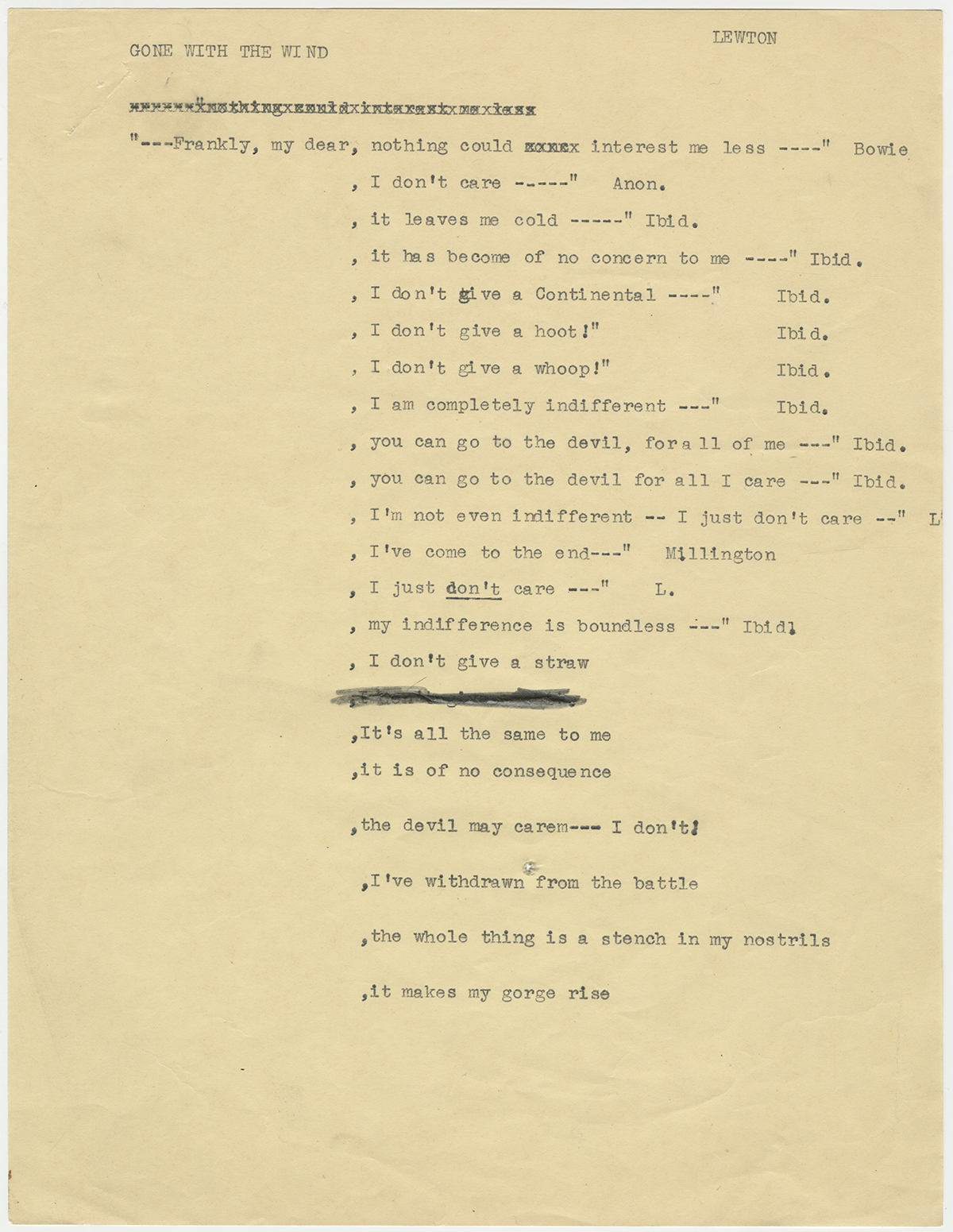

The iconic last words of Rhett Butler in Gone With The Wind almost weren’t, because use of the word “damn” in films was expressly prohibited in the Production Code. Anticipating objections by the Hays Office (the entity that governed moral code in film), producer David O. Selznick asked his story editor, Val Lewton, to compile a list of uses of the word “damn” in print media and, if possible, cinema.

A list of alternate lines was also compiled, including such gems as:

“Frankly, my dear, nothing could interest me less.”

“Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a hoot!”

“Frankly, my dear, my indifference is boundless.”

“Frankly, my dear, the whole thing is a stench in my nostrils.”

Selznick knew that the Code would have to be changed for him to be able to keep Rhett Butler’s final line, a change that could only be approved by the board of directors. Leading up to a decisive October 27, 1939, meeting, Selznick and business partner Jock Whitney lobbied board members to change the Code. Although deliberations were described as “very stormy,” Selznick prevailed, and the Production Code was amended to make future use of the word “damn” discretionary.

Although Selznick promised to “put up a strong fight for the line,” he took Lewton’s precautionary advice to film the scene twice, once as written, and a second time substituting “Frankly, my dear, I don’t care.”

What would you have suggested as an alternate line? Give us your best family- and censor-friendly versions of the line via Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram using the hashtag #franklymydear.