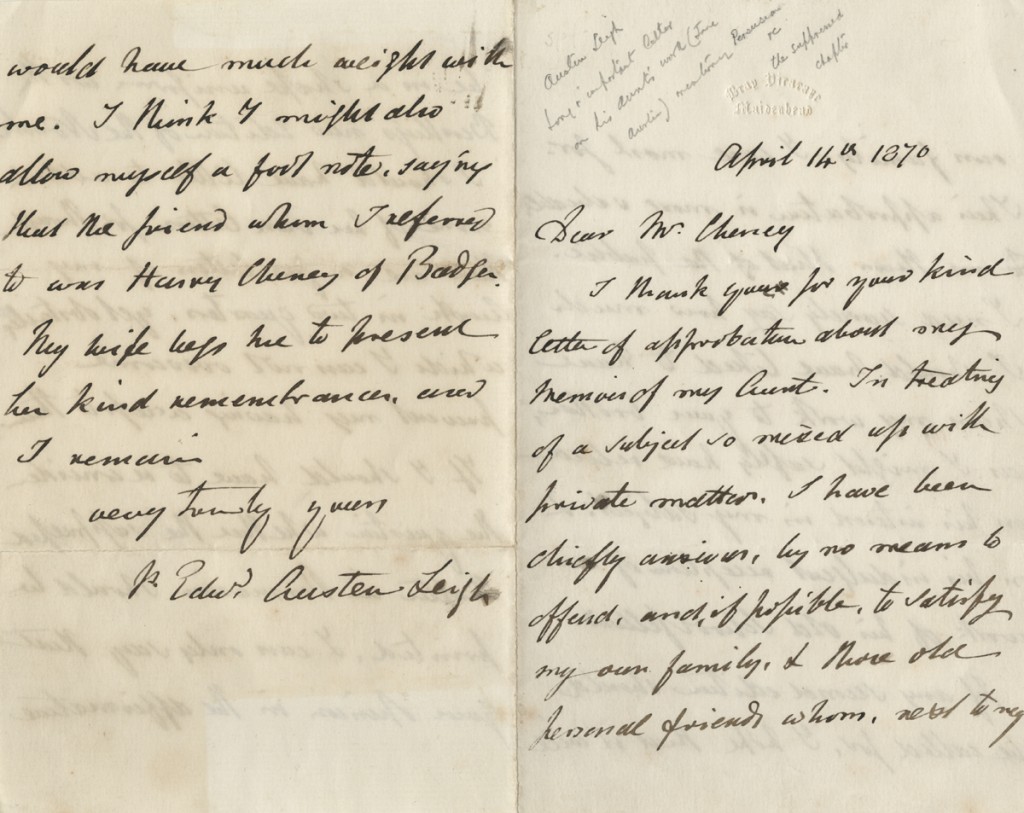

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mansfield Park, Jane Austen’s most ambitious and controversial novel. To celebrate both the author and the cultural history behind this complex work, students in English Professor Janine Barchas’s fall 2013 graduate seminar curated two display cases relating to Austen and her culture. Below, students Chienyn Chi, Dilara Cirit, Gray Hemstreet, Brooke Robb, Megan Snell, and Casey Sloan share some of the items displayed.

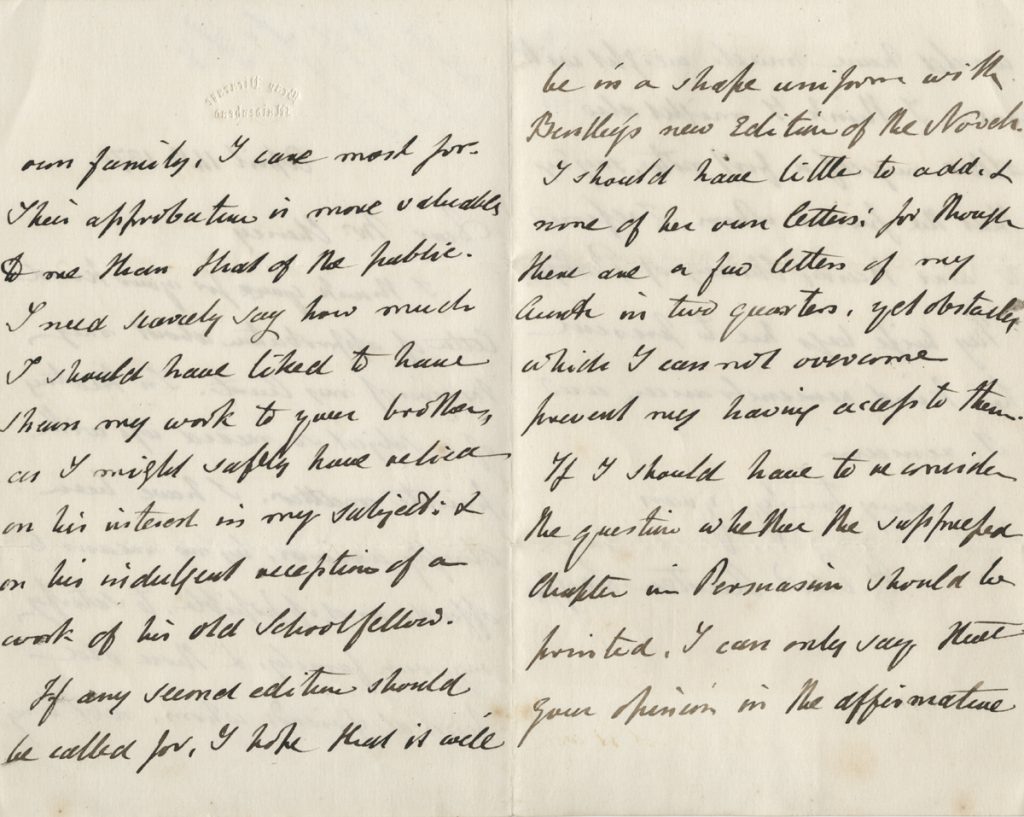

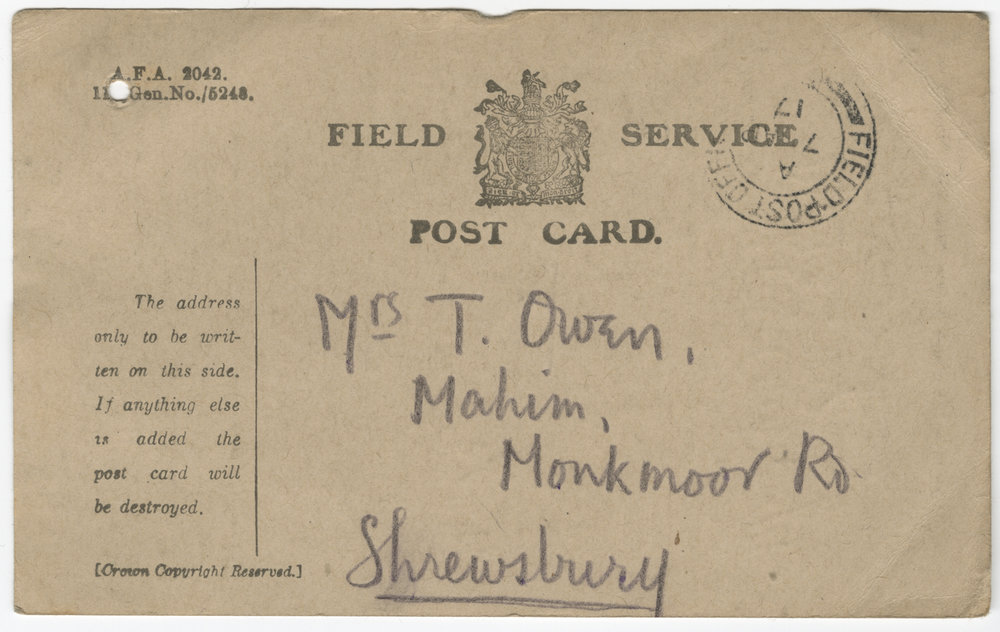

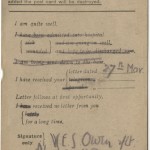

From family correspondence to uniquely inscribed copies of the novels, the Jane Austen items held by the Harry Ransom Center allow us a rare and intimate view of this beloved author. Georgian fashion plates, landscape illustrations, and other Regency-era artifacts further help to illuminate the culture in which Austen lived and wrote. This display can be seen during reading room hours through May 30.

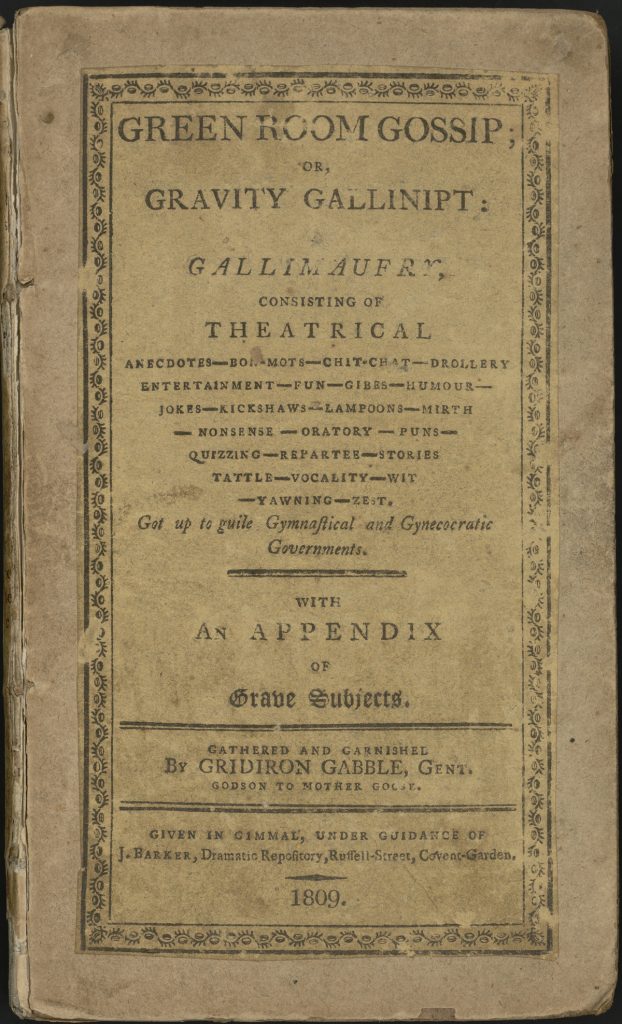

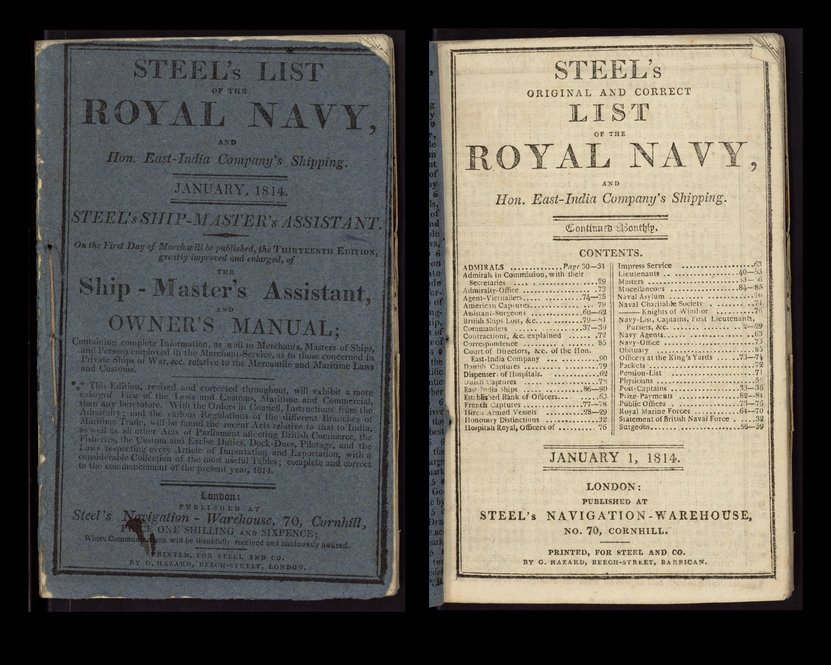

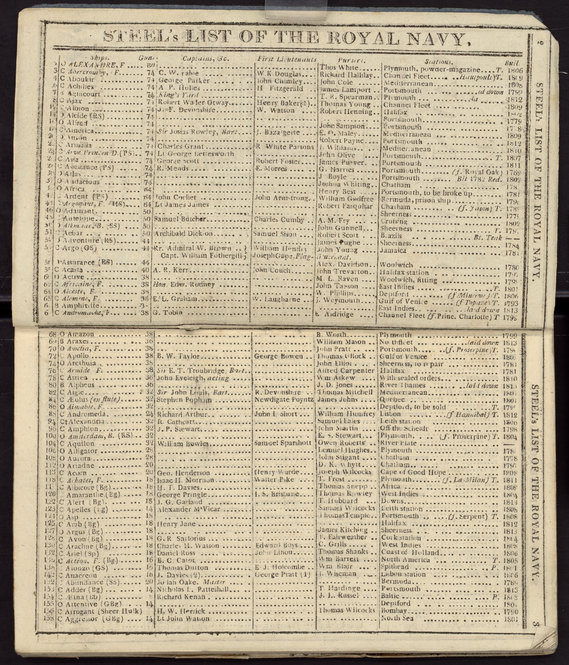

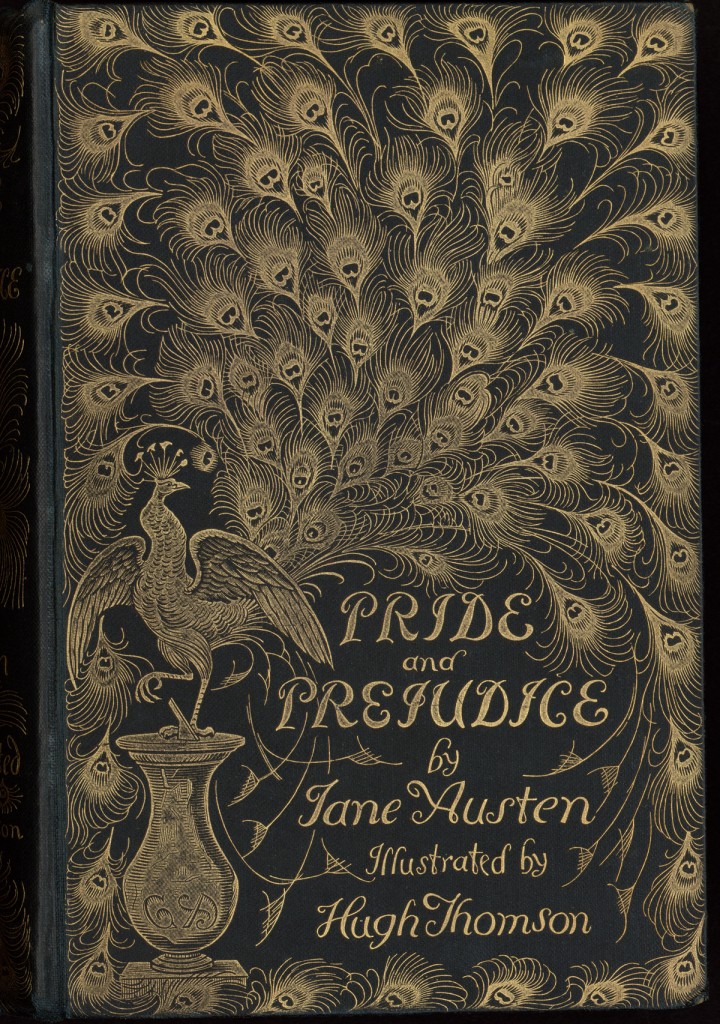

One case contains items relevant to the world described in Mansfield Park, first advertised as published on May 9, 1814. In telling the story of the modest and physically fragile Fanny Price, Austen created a complex and challenging work that critics often contrast unfavorably with the more popular Pride and Prejudice, in which the heroine is pert and talkative. Austen herself judged Pride and Prejudice “rather too light & bright & sparkling.” In Mansfield Park, Austen alludes to the vogue for large-scale “improvements” by popular landscaper Humphry Repton, sentimental drama and theater culture, and the Royal Navy’s role in the Napoleonic Wars. Such references reveal Austen’s awareness of the large cultural concerns of her day.