Scott Balcerzak is Associate Professor of film and literature at Northern Illinois University. He was supported by the Dorot Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Jewish Studies and is currently writing a book on Stella Adler and male movie stars. [Read more…] about Fellows Find: Hear inside Stella Adler’s studio

Lee Strasberg

Fellows Find: Stella Adler and Harold Clurman papers shed light on evolution of Method acting

Justin Owen Rawlins is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Communication and Culture and the Department of American Studies at Indiana University. He visited the Ransom Center in May and June 2013 on a dissertation fellowship to conduct research for his dissertation, “Method Men: Masculinity, Race and Performance Style in U.S. Culture.”

Through a generous fellowship from the Harry Ransom Center, I was recently afforded the opportunity to conduct extended research for my dissertation on the historical reception of Method acting. My interest in the terms and conditions under which Method acting—and actors—accumulate meaning in U.S. popular culture led me to the Center’s Stella Adler and Harold Clurman papers. As founding members of the Group Theatre (1931–1940), Adler and Clurman were part of an ostensibly communal organization offering socially-engaged theatrical alternatives to the commercial New York stage. More importantly, the Group functioned as a crucial transitionary device, adapting the work of Constantin Stanislavsky and others to suit its own purposes and cultivating a community of performative philosophers—including, but not limited to, Stella Adler, Robert Lewis, Morris Carnovsky, Sanford Meisner, Cheryl Crawford, Harold Clurman, Lee Strasberg, Elia Kazan, Clifford Odets, and Phoebe Brand—whose teaching, writing, directing, and producing continue to permeate U.S. culture in ways we may never fully understand. Though it lacks the name recognition of some of its alums (especially Adler, Meisner, Strasberg, and Kazan), the Group has long been ensconced in the mythology of the Method.

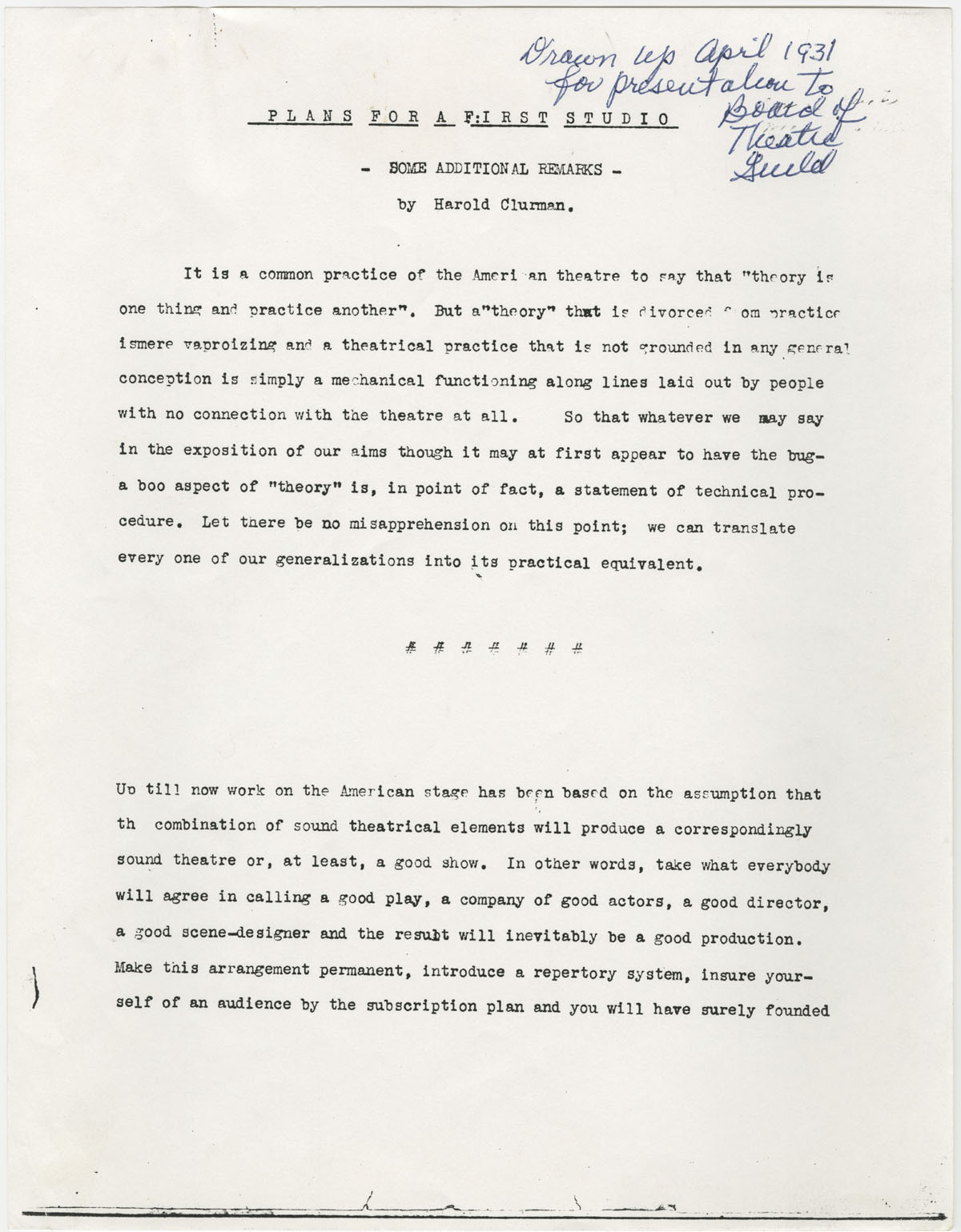

As the Adler and Clurman papers make clear, however, the lore surrounding the Group belies a more complicated organism. The April 1931 “Plans for a First Studio,” attributed to Clurman, provides us several examples in service of this reality. Although the “Group” did not yet formally exist, the case put forth in these “Plans” to the Board of The Theatre Guild (1918–) gives us a sense of the terms—and the tone—undergirding the proposed “First Studio” in this document and the eventual Group Theatre in reality. “Plans” also displays the careful negotiation of organizational philosophy and identity at work. The proposed First Studio is inextricably linked to The Theatre Guild, with Clurman’s historical narrative explicitly identifying the Guild as the medium through which this eventual group coalesced. At the same time, however, the mere proposal for a separate Studio carries with it this community’s desire to extend to forms of artistic expression beyond the ascribed capacity of the Guild.

The document also unintentionally highlights the difficulties in bridging acting language and practice. Clurman seeks to put the question to rest immediately, declaring in the first paragraph “[l]et there be no misapprehension on this point; we can translate every one of our generalizations [regarding theoretical practice] into its practical equivalent.” In fact, the remainder of the “Plans” presentation struggles to uphold this pronouncement. The ensuing existence of the Group is defined by many such debates revolving around the same gap between language and performance. As Clurman later admits in the very same “Plans,” “[i]f such a reply seems evasive it is not because we are vague as to what we want but because words are so inadequate for the definition of essences and because a lack of a common vocabulary creates so many harmful barriers in the minds of those that hear them.”

Exploring the factors that widen this gap and its cultural repercussions enable us to further demystify the Group Theatre and other Method-aligned organizations and figures. The Clurman and Adler papers are integral to that project.

Related content:

The Ransom Center is now accepting applications for the 2014–2015 fellowship program.

Image: First page of “Plans for a First Studio” from the Stella Adler and Harold Clurman papes.

Stella Adler scholar explores acting master’s interpretation of great American playwrights

“Mommy, is that God?” a little girl once whispered to her mother as Stella Adler swept into a party in New York City. The girl’s mistake was understandable: Adler was known as a presence of divine proportions, a tall, glamorous woman whose grand gestures and dramatic one-liners captivated audiences both large and small. Adler began acting at age four in the “Independent Yiddish Art Company,” run by her parents, and continued her acting career until 1961. In 1931, Adler joined the Group Theatre, where she worked closely with Harold Clurman and Lee Strasberg.

In 1934, she went with Clurman to Paris to study with Constantin Stanislavski, an acting great famous for developing the Stanislavski System, a set of acting techniques that was tweaked by Strasberg and is known today as Method acting. Adler believed strongly that actors should use their imagination to synthesize characters, whereas Strasberg relied on emotional memory exercises, and the two eventually split over their differences. Adler left the Group Theatre and later opened her own acting school, The Stella Adler Studio of Acting, in 1949 in New York City, where she taught famous actors such as Marlon Brando and Robert De Niro. She opened another school, The Stella Adler Academy of Acting, in Los Angeles in 1985 with her friend and protégé Joanne Linville, who continues to run the school today.

The Ransom Center hold Adler’s papers, which were used extensively by Barry Paris in his book Stella Adler on America’s Master Playwrights (Knopf). The volume peeks into Adler’s classroom and explores the acting master’s take on American playwrights such as Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, Edward Albee, Clifford Odets, and others.

The book was put together using transcripts from Adler’s script analysis classes, where lively discussions of American culture, socioeconomics, and history fleshed out the context of the plays—a practice on which Adler placed the utmost importance. Adler once said of the great artists featured in the book: “these playwrights all saw what was wrong.” She believed it was imperative for the actor not only to bring personal experience to the role, but to truly understand the beliefs, prejudices, and lives of the playwrights who crafted the plays she taught. Peter Bogdanovich, one of Adler’s former students, praised the book for “bring[ing] back the sound of Stella’s unique voice and thought processes, as well as her own particular vision.”

Paris, the book’s editor, did extensive research in the Ransom Center’s holdings on Stella Adler and Harold Clurman.