Helen Shenton, Librarian and College Archivist of Trinity College Dublin, Ireland, presents “The Library of the Future; the Future of the Library” on Thursday, March 2, at 7 p.m. CST. This event will be livestreamed via the Harry Ransom Center’s Facebook page.

[Read more…] about “The Library of the Future”

libraries

Scholar: Will libraries of the future preserve cultural heritage?

Michele V. Cloonan, Professor at Simmons College and Editor-in-Chief of Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture, presented the talk “Exeunt Libri: Will Libraries of the Future Preserve Cultural Heritage?” for the 2013 Donald G. Davis, Jr. Lecture on Thursday, October 17. Below, she shares her thoughts about preservation.

Preservation is all around us. It encompasses continuity and change. I first encountered issues of preservation as a child living in Hyde Park, on Chicago’s south side. Three particular touchstones have stayed with me. One was the dismantling of the Fifth Army Base on the Promontory Point. While there was wide-spread support for it to be closed, some people advocated for the preservation of parts of the installation, so that there would be a permanent record of the site.

A second touchstone was the Museum of Science and Industry, my next-door neighbor. I explored every outside nook of it as a child and was intrigued by what little I knew of its history. Built as The Palace of Fine Arts, it was constructed for the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. One had to be captivated by this building, the only one to survive the vast White City.

Finally, the demolition of a beautiful brownstone apartment complex across the street from my house, which was replaced by a less-attractive high-rise, made me think about preservation as I watched people collect tiles and light fixtures right before the wrecking ball destroyed the building.

In ways like this, we are all touched by preservation. Each community shares its own stories of the old—and the newer. Most communities contain some legacies of their past, which may become “Places of Memory” (Lieux de Memoires, as Pierre Nora refers to them). Other historical artifacts are destroyed, or their sites become neglected. We contemplate the presence, as well as the absence, of cultural artifacts. They are part of our memory.

The rise and fall of physical monuments are part of the preservation continuum of cultural heritage.

As an adult, I have written about preservation, focusing mostly on libraries, archives, and museums. For my talk at the Harry Ransom Center, I will focus on preservation, memory, and libraries. Libraries represent many things. They may be storehouses of books and manuscripts, information centers, classrooms, and community living rooms. At the same time, the library exists in many physical and digital forms, some analog, others virtual. As a metaphor, the library may represent a fictional place (Jorge Luis Borges), or the concept of a library may occur within other metaphors such as the World Brain (H. G. Wells), the Memex (“memory” + “index”) (Vannevar Bush), or the Internet.

The Ransom Center is the perfect place in which to consider the interplay between preservation, memory, and libraries because it has been a leader in the American preservation and conservation movement; a preeminent collector of books, manuscripts, and objects; and a research center. Its original “temple-of-knowledge” architecture/building is now complemented by dramatic accents of glass, which invite us to reflect on its collections in new ways.

Letters in Knopf archive show challenges Ray Bradbury faced early in his career

Legendary science fiction writer Ray Bradbury, author of the classics Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, died last Wednesday at the age of 91. In his long writing career, Bradbury published hundreds of novels and short stories, becoming an icon in the world of literature that describes aliens, space ships, faraway planets—and the future of books.

Like the 13-year-old characters in his Something Wicked This Way Comes, Bradbury spent much of his boyhood visiting the public libraries of his Midwest hometown, where he was inspired by the works of such writes as Aldous Huxley, Jules Verne, and H. G. Wells. Throughout his life he was an enormous supporter of libraries, advocating them as some of the most important institutions in American life and culture. The son of an electrician father and a Swedish immigrant mother, Bradbury lacked the means for a formal college education and prided himself on being largely self-taught. In 1971, in aid of a fundraising effort for public libraries in southern California, he published the essay “How Instead of Being Educated in College, I Was Graduated From Libraries.” Like the characters in his most famous novel, Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury feared a future wherein books would become obsolete.

Bradbury faced an arduous challenge in making his own futuristic novels part of the libraries he so dearly loved. Early in his career, he had difficulty garnering interest for his science fiction stories from mainstream publishing houses. He was famously “discovered” by a young Truman Capote, then a staff member at Mademoiselle, who picked Bradbury’s 1947 short story “Homecoming” out of the slush pile of submissions to the magazine and encouraged its publication. The Alfred A. Knopf archive at the Harry Ransom Center, however, reveals that despite Capote’s early advocacy, Bradbury continued to meet with difficulties when seeking a home for his work. In a rejection letter from 1948, a reader at the publishing house professes hesitation toward Bradbury’s first novel, Dark Carnival. The evaluator states that though there is “much talk about town” of Bradbury’s “weird, unusual, and tricky” stories, “the style, while adequate, lacks distinction.”

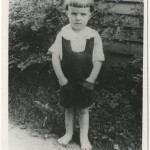

Three decades later Bradbury, by then a seasoned author with dozens of publications to his credit, became a highly valued writer at the Knopf firm. During the 1970s he worked closely with editors Robert Gottlieb and Nancy Nicholas, who published his Where Robot Mice and Robot Men Run Round in Robot Towns, Dandelion Wine, and When Elephants Last in the Dooryard Bloomed, among others. In a letter to Nicholas (shown in the slideshow above), Bradbury, who often wrote nostalgically of childhood, included a picture of himself at the age of three. He jocularly describes the photograph as “beautifully serious, as if the young writer had just been disturbed in the midst of some creative activity.”

The Ransom Center also houses manuscripts and letters related to Ray Bradbury in its Lloyd W. Currey, Sanora Babb, Eliot Elisofon, Lillian Hellman, B. J. Simmons, and Tim O’Brien archives. Additionally, the Ransom Center’s Lewis Allen collection contains screenplay drafts, correspondence, casting notes, call sheets, and promotional materials for François Truffaut’s 1966 film adaptation of Fahrenheit 451.

Please click on the thumbnails below to view full-size images.