In 1943, the Allies of World War II established the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Program—an organization tasked with recovering, restoring, and returning stolen or lost cultural artifacts. The members of the MFAA, known as the Monuments Men, included over 300 artists, architects, educators, directors, and scholars. Together, they made an unprecedented effort toward cultural conservation.

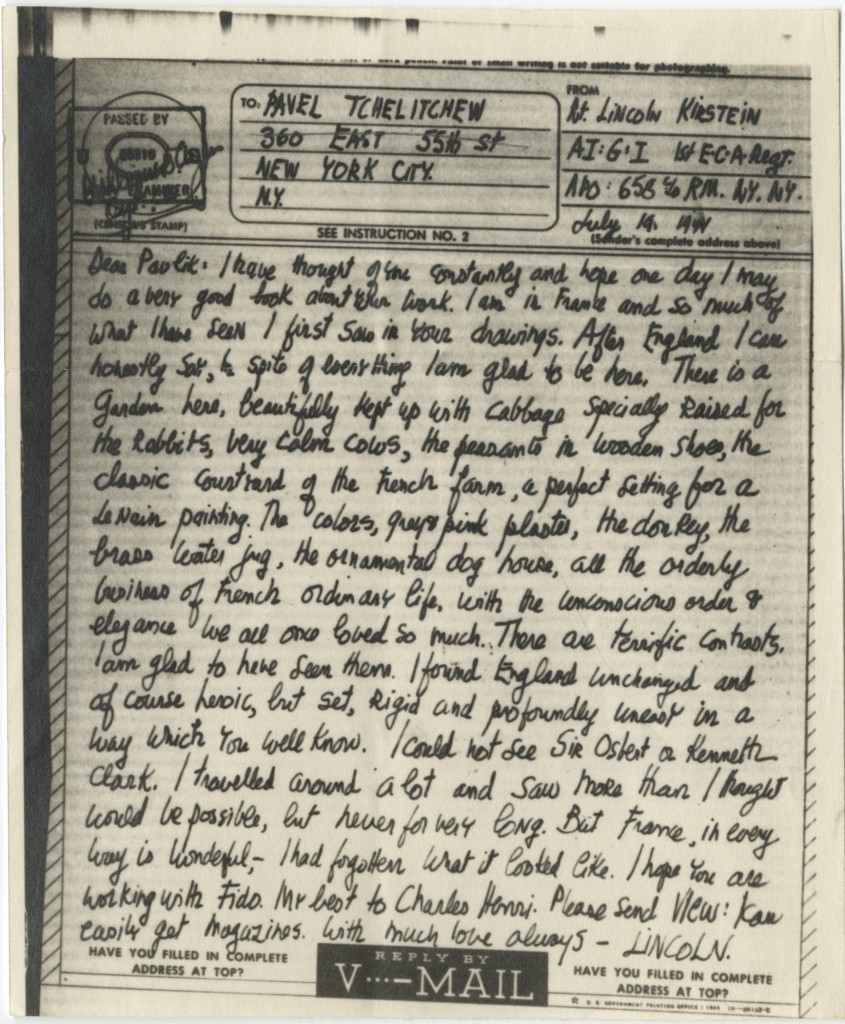

Lincoln Kirstein—art critic, writer, and co-founder of the New York City Ballet—served the Monuments Men in France and Germany from 1944 to 1945. While abroad, he maintained a close correspondence with Russian artist Pavel Tchelitchew, whose archive resides at the Ransom Center.

Through his letters, Kirstein expresses a deep reverence for his responsibilities and appreciation for the artwork itself. His solemnity is, however, shrouded by a veil of casual quips. On March 10, 1945, Kirstein candidly opens his letter to Tchelitchew by writing, “As you know, my work is to help prop up what war has knocked down, and to try to pick up the pieces if there are any left, to try to keep people from scratching names on carved stone and if an armoire is broken it need not be used for kindling.” Yet, to be sure, Kirstein does not ignore the severity of the situation. He closes the same letter by writing, “Do not believe that the war will either be over early or easily. I don’t read the newspapers, but I don’t have to.”

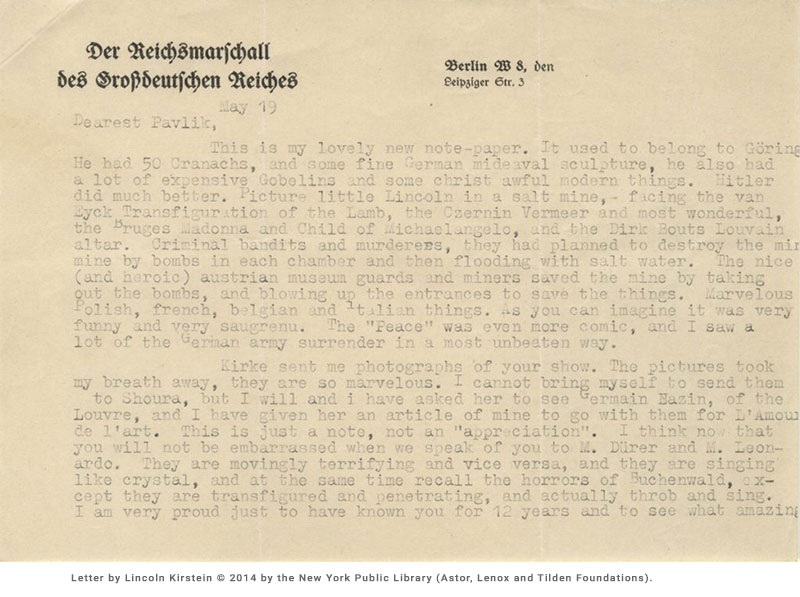

By May, Kirstein’s “work” was more exciting. He writes to Tchelitchew on German stationary—which he claims belonged to Nazi leader Hermann Göring—of a recent near-disaster.

“This is my lovely new note-paper. It used to belong to Göring. He had 50 Cranachs, and some fine German medieval sculpture, he also had a lot of expensive Gobelins and some christ awful modern things. Hitler did much better. Picture little Lincoln in a salt mine, facing the van Eyck Transfiguration of the Lamb, the Czernin Vermeer and most wonderful, the Bruges Madonna and Child of Michaelangelo, and the Dirk Bouts Louvain altar. Criminal bandits and murderers, they had planned to destroy the mine by bombs in each chamber and then flooding with salt water. The nice (and heroic) austrian museum guards and miners saved the mine by taking out the bombs, and blowing up the entrances to save the things. Marvelous Polish, french, belgian, and italian things. As you can imagine it was very funny and saugrenu. The “Peace” was even more comic, and I saw a lot of German army surrender in a most unbeaten way.”

By July, however, this excitement again waned. Kirstein complains to Tchelitchew of “nothing but tedious work and horrible Germans,” laments that there is “absolutely no one to talk to,” and describes himself as a “gloomy intellectual misfit.”

Perhaps partially instigated by boredom, Kirstein then shifts his rhetoric from that of dismay to that of veneration. He writes:

“Yesterday I had a very exciting day, as I was left alone and went down to Hitler’s house which is our art-collection depot, and spent the whole day looking at really amazing pictures. They are stacked up like books against the wall, and the frames are often heavy, but the glories are undiminished. Painting is so wonderful. Few people but you know the secrets of the renaissance attitude, the absolute devotion to the métier, the rewards of glorious workmanship and heavenly color.”

He continues by praising Titian and Raphael, Watteau and Vermeer, while also adding a bit of personal, poetic color:

“Also a lot of other unimportant pictures, a picture I guess you would not like but which is so wonderful, a lot of cowy cows and very tawny horsy horses, in a wild later summers landscape with all the leaves madly tossing against wild clouds, and the horses sniffy and neighing with pleasure, in the midst of which a very heavy healthy pink sexy goaty old man is flirting with Mercury who wears a sort of orange satin Turkish towel, Rubens, on an oak panel, fresh as a daisy and absolutely the packed-up glory of sensuality.”

These accounts of his service constitute a small part of Kirstein’s letters, usually claiming only a paragraph here and there. He preferred, it seems, to write to Tchelitchew about what was to him most familiar and precious: art, artists, friends, and ballet. Between insults directed at the Germans, he playfully teases the likes of Pablo Picasso and Ezra Pound. While writing of recovered Rembrandts, he begs to be sent copies of contemporary magazines. Thus, through his letters, Lincoln Kirstein displays a fundamental characteristic of the Monuments Men: he was one of many artists working in the service of art.

The film The Monuments Men, directed by George Clooney and starring Clooney, Matt Damon, and Bill Murray is in theaters now. The film is based on Robert Edsel’s book of the same title.

Letter by Lincoln Kirstein © 2014 by the New York Public Library (Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations).

Please click on the thumbnails below to view full-size images.