James Sitar is an editor at the Poetry Foundation and teaches literature classes at Loyola University Chicago. Sitar’s work in the Spalding Gray archive was supported by the Andrew Mellon Foundation. He discusses his digital project that allows comparisons between Gray’s performance notebooks. The Ransom Center is celebrating the 25th anniversary of its fellowship program in 2014–2015.

Many who know of Spalding Gray’s storytelling first experienced it by watching the film version of Swimming to Cambodia or by reading the book. Gray performed over a dozen different monologues, but this one catapulted his career and ensured that his innovative performance style would influence a new generation of actors. I was certainly captivated by the movie when I was 10 years old (which was probably too young). And ever since my college days, I’ve been drawn to archival recordings, whether it was the all-encompassing lectures or “talks” of Robert Frost or the countless bootlegs of Bob Dylan. When I heard that the Harry Ransom Center acquired the archive of Spalding Gray, including scores of audio and video recordings, I knew I had to visit. After all, how often do your childhood fascinations align with your interests as an adult?

Thanks to a fellowship from the Ransom Center, I was able to spend a month listening to and comparing Gray’s performances of Swimming to Cambodia, which occurred over a span of about 20 years. Gray would record his one-man shows and then listen to them the next day, and this listening would inform his approach to the next performance. No performance is the same, which means that this monologue is what we refer to as a living text: there’s no one version of it that is more important or authentic than any others. It’s clear from interview and diary entries that he never thought of the film or the book versions as definitive or superior performances, though certainly he viewed them as successful versions that were true to the mediums of film and print.

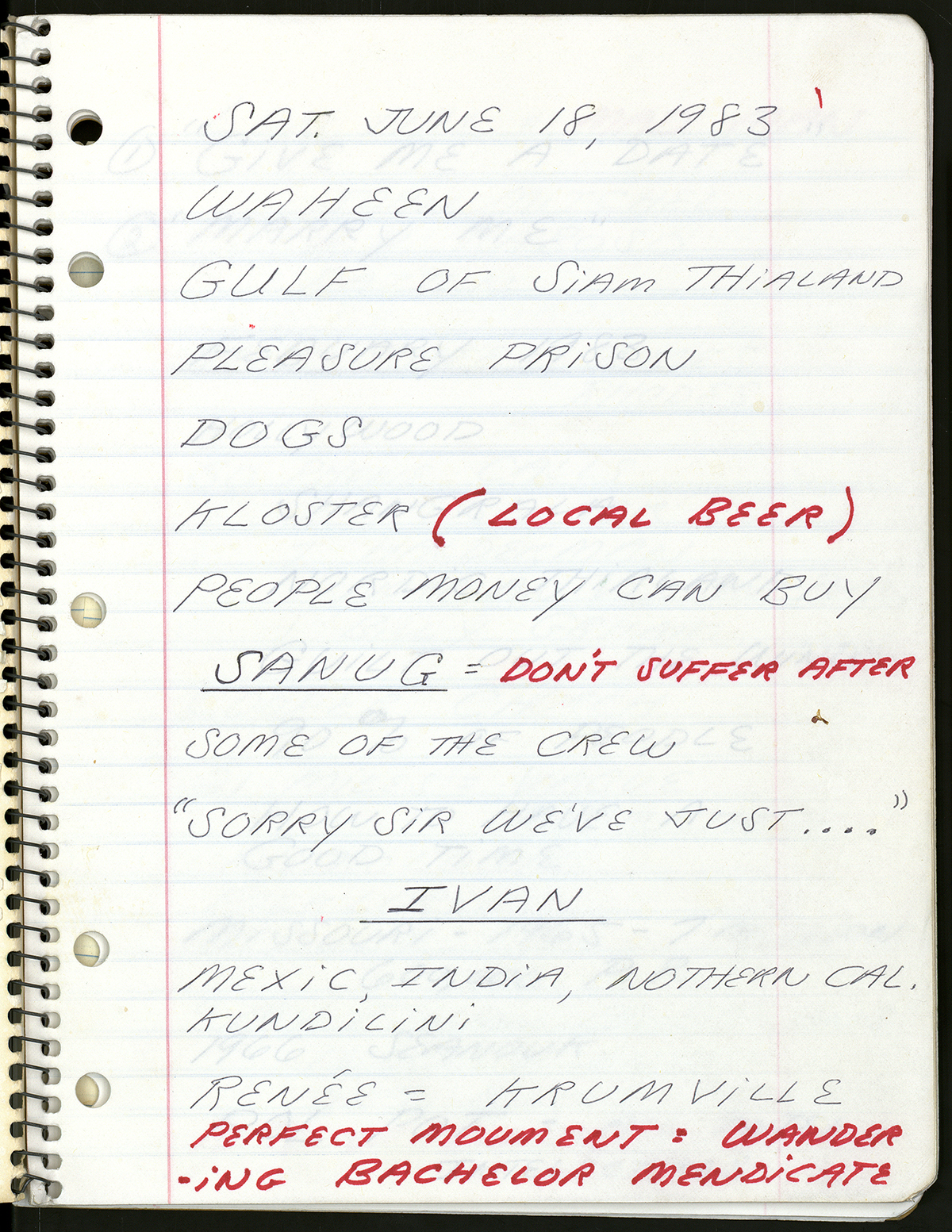

By listening along, I discovered how important this flexible, evolving, experimental approach was to Gray. He never worked with a script, or even solidified particular details or vignettes. Instead, he’d only sparingly glance at the spiral-bound notebook he had on stage, in which he had written certain important words or phrases; if he got caught up in a tangent, as he was wont to do, his notes would help him find his way back to his narrative arc. The opportunity to perform in person, in front of small audiences, was crucial to Gray. His loose narrative style and method, and his desire to make each performance a unique connection to place and time and audience, make each performance different. This fact also reflects his avant-garde approach to theater and his artistic preoccupations with the evolving natures of memories, the construction of personal truths, the production and performance of a public self, and the complications of making art out of life through the problematic notions of authenticity and confession.

As a researcher and editor, I want to deliver remarkable materials into the hands and ears of fans and scholars and to present these materials in the most helpful, enjoyable, responsible, and authentic ways possible. I’m currently building a website devoted to Swimming to Cambodia that’s true to the living nature of the monologue, with audio and video recordings, notebooks, and different types of transcripts with annotations and background materials that allow visitors to experience the monologue’s myriad iterations. I want to present Gray’s performances as moments, as I look for innovative ways to preserve some of the fluid and ephemeral essences of speech and performance in the fixed form of text. It will serve as an archive that collects all of the Swimming to Cambodia’s that we can revisit.

You can take a look at a very early and small sample of the work, which uses an inventive piece of software called the Versioning Machine. This sample presents the same passage from many different notebooks and performances of the monologue, a passage in which Gray chronicles his difficulty remembering some lines in filming The Killing Fields (1984). It’s Gray’s inability to memorize lines that makes this part of the monologue so funny and painful, and this inability is also what makes his monologues so unscripted and alive. It’s a revealing moment behind the scenes of filmmaking, and I hope my digital project can similarly look behind the scenes of Gray’s craft.

I’m grateful for and indebted to so many people’s help in making Gray’s work available online, including Tanya Clement, Quinn Stewart, Daniel Carter, Erin Donohue, the entire Ransom Center staff, and the estate of Spalding Gray.

Related content:

Ronald McDonald swims to Cambodia: A first glimpse at Spalding Gray’s notebooks

An iconic photographic moment with Spalding Gray

“The Journals of Spalding Gray”: An interview with editor Nell Casey

A Graduation Diploma: “The Eviction Notice Written in Latin”

Image: First page from Spalding Gray’s performance notebook for Swimming to Cambodia.