by Harsha Gautam

The fiction of Indiana Jones found competition in the real-life encounters of Dr. Sonya Rhie Mace, the George P. Bickford Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art at the Cleveland Museum of Art and Adjunct Professor of Art History at Case Western Reserve University, who delivered a talk on November 7th, 2022, entitled: Repatriation, Cooperation, and Exchange: Three Case Studies in Cambodia and shared her first-hand experiences with three monumental Khmer antiquities that moved between sites and museums in and out of Cambodia.

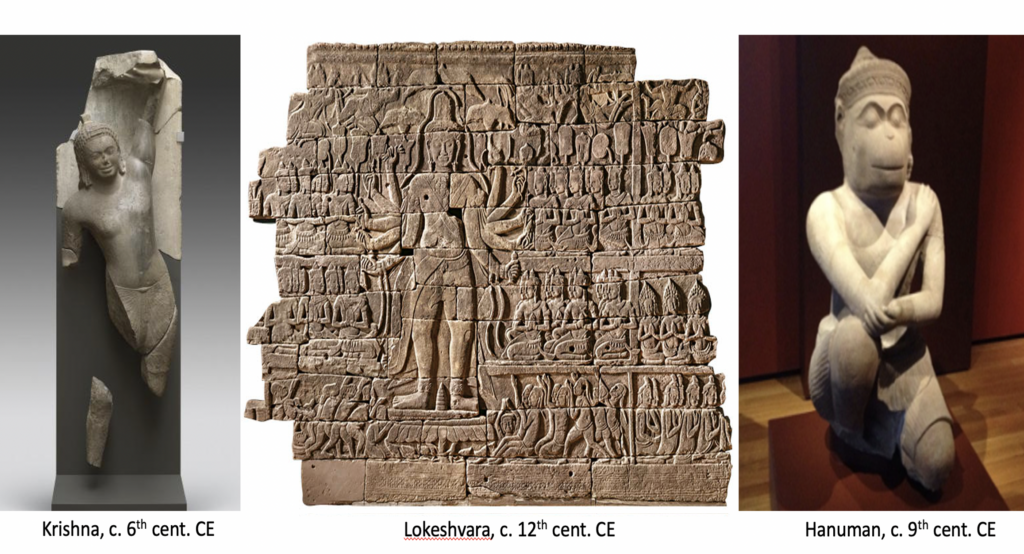

Her detailed narrative of the journeys of a sixth-century Krishna sculpture from Phnom Da, a ninth-century Hanuman sculpture from Koh Ker, and a twelfth-century Buddhist Lokeshvara from Bantaey Chhmar, from Cambodia, to private collections to museums to Cambodia again, showed how an important but often overlooked institution played a significant role in facilitating these expeditions, scilicet, the museum.

Introducing Dr. Mace to a packed audience, art historian Dr. Janice Leoshko, remarked how museums allow sitting objects to be turned over to reveal new information. The talk further revealed how museums become sites of interaction and collaboration of experts from various disciplines, such as history, archaeology, religion, anthropology and digital experts, to not only explore the multitude of facets of an object, but more importantly to contextualize the artifact both in its own historical time and space and in the spatio-temporal location of the audience at the museum. The religious objects in museums make for an interesting case study in this regard, and Dr. Mace’s talk weaved three fascinating narratives of religious objects from the Hindu and Buddhist religious traditions of medieval Cambodia.

She began her talk with the story of a sixth-century sculpture discovered from a bat-infested cave in Phnom Da in 1911, that found no takers in the form of worshippers in a Buddhist majority country for it was an unfamiliar Hindu deity, Krishna lifting the Govardhan mountain. Exchanging hands through French military personnel, a French sailor, and a European art dealer, this sculpture finally found a home in the music hall of a Belgian palace in Brussels, Palais Stoclet, and was baptized as ‘the dancing prince’ by the owners. While this sculpture was to bear its new name until it was rediscovered in the 1960s, another sculpture of Krishna lifting the Govardhan mountain revealed itself in the cave adjacent to the previous one. This sculpture invited earnest attention of the locals and, in consequence, was refashioned as a Vietnamese-styled Buddha and made its home as the destination of the worshippers, visiting to pay homage to their Lord Buddha. These two sculptures might have remained in their inapt abodes, if not for the intervention of the museums.

In 1973, the sculpture from Brussels was acquired by the Cleveland Museum of Art and around the same time, the one in the cave was taken by the National Museum of Cambodia, which also left behind a plaster cast of the Buddha, for the worshippers to continue revering their deity. During their journeys through caves, continents, worshippers and institutions, the sculptures lost significant fragments (seventeen of those were eventually discovered) and what remained intact were the torsos. It was these incomplete torsos, that were to sediment long-term communication and exchange between the Cleveland Museum of Art and the National Museum of Cambodia. When successful modes of interactions were established, and the remaining fragments were distributed between the two institutions, it was discovered that the limbs of one belonged to the one on the other end of the planet.

Through the diligent efforts of Dr. Mace and others in charge, the exchange of the limbs was successfully made, after the Cleveland Museum offered to send its beloved sculpture from ninth-century Cambodia, one that of a sitting Hanuman from Koh Ker, as a token of friendship and collaboration to Cambodia’s National Museum.

This sculpture of another popular Hindu deity had its own share of striking snippets from its travelogue through lands and ages. Traveling on the back of a farmer’s elephant, it was sold at the border of Thailand for a sum of $100 in 1967, passed through private collections in the 1980s, and finally become a kids’ favorite at the Cleveland Museum. In traveling back home to Cambodia as a token of goodwill, this sculpture of Hanuman solidified channels of international communication and opened many doors of opportunities for the expansion of museum expertise in Cambodia.

The last object that concluded Dr. Mace’s fascinating talk was a ten-armed Lokeshvara, one of the original eight life-sized Bodhisattvas, from Bantaey Chhmar in Northwest Cambodia. This artifact stands out as an example of what can be called ‘complete repatriation’, as it not only made its way back from the Cleveland Museum to the country of its origin, but also to the exact historical site it was looted from. Through the industrious work of an NGO, Heritage Watch, the temple complex at Bantaey Chhmar was revived, ensuring livelihood for the local villagers through tour guide and home-stay programs and weekly visits of the local student community.

Dr. Mace took the opportunity of emphasizing the necessity of building friendly networks and continued international cooperation to an attentive audience, not only to enhance the knowledge and professional experience with these objects, but to also cultivate care for them. Her recent curation at the Cleveland Museum, entitled, Revealing Krishna: Journey to Cambodia’s mountain, tells the success story of international cooperation and exchange of knowledge that manifested in the form of it becoming the highest-rated exhibition at the museum. By venturing with these objects through digital galleries, as the objects made their way through historical time and space to greet them in stone in the final gallery, the visitors on the soil of the States were not only able to learn immensely about a distant religious tradition but were also able to build a personal connection with these antiquities.

About the Speaker:

Sonya Rhie Mace is the George P. Bickford Curator of Indian and Southeast Asian Art at the Cleveland Museum of Art and Adjunct Professor of Art History at Case Western Reserve University. Previously, she served as the Curator of Asian Art at the San Diego Museum of Art and taught classes in South Asian and Himalayan art history at UC Irvine, UCLA, and UC San Diego.

About the Author:

Harsha Gautam is a Ph.D student in the Religions in History track at the Department of Religious Studies at UT, Austin. She specializes in the study of premodern South Asia, early Buddhism, Sanskrit and Pāli literature and South Asian Art. Her research interests also include religious identity-formation, power relations, comparison and intellectual history.