by Blake Pye

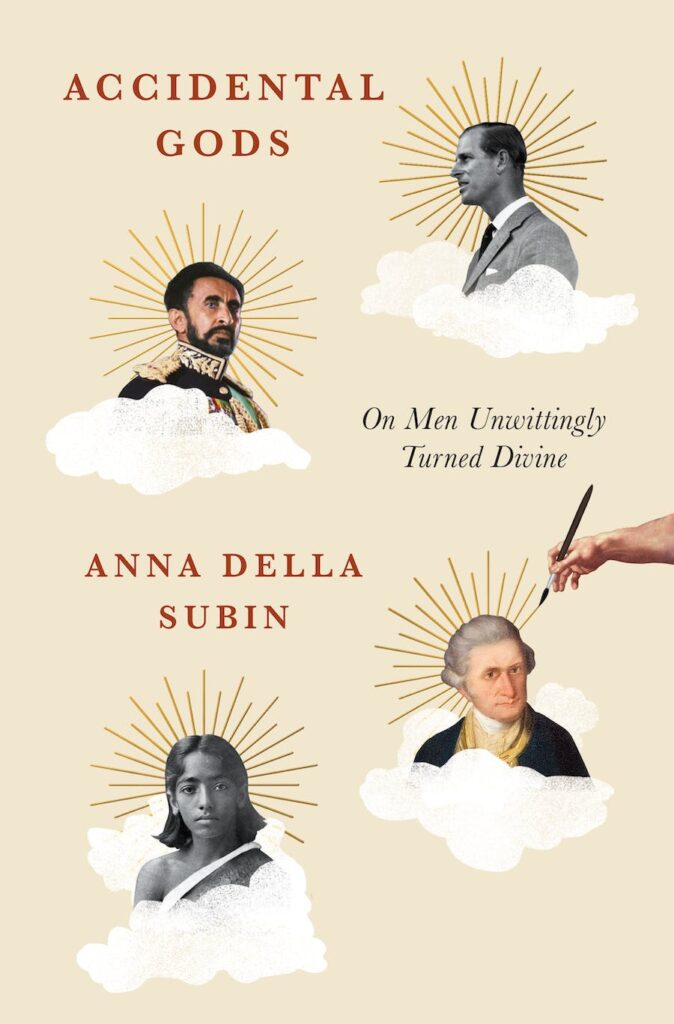

Accidental Gods: On Men Unwittingly Turned Divine by Anna Della Subin

New York: Metropolitan Books, 2021. 480 pgs. $35.00. Hardcover. ISBN 9781250296870.

Crafted with a general audience in mind, Accidental Gods is an engagingly written history of divinizations of humans in the modern era. Author Anna Della Subin, in response to those who would say that our world is disenchanted and the apotheosis of humans a thing of the past, shows how new divinities have regularly ascended since the dawn of Western colonialism. She further attempts to demonstrate that these deifications benefited from the modern Western conceptualizations of race and religion. In three parts roughly divided along the lines of decolonization, the rise and fall of British India, and the deification of whiteness in the Americas, this book centers on several deified individuals, some of whom include Prince Philip, US General Douglas MacArthur, Captain James Cook, and even some anthropologists.

The problem space of Accidental Gods is confined to the encounter between globe-traveling Europeans and indigenous cultures without writing, whose religious worldviews and attitudes make possible the deifications studied in the book. For European Christians, divinity was singular, abstract, and incomparable to humans, while for the indigenous peoples they came into contact with, and eventually conquered and colonized, divinity is diffuse, a matter of empirical reality, and applicable to living humans. The encounter between the two modes of thinking, many new gods were created and perceived. Indeed, as Della Subin states evocatively—her prose makes this book a joy to read—the making of gods is in humanity’s very nature:

Gods are made in sudden deaths, violent accidents; they ascend in the smoke of a pyre, or wait, in their tombs, for offerings of cigars. But gods are also created through storytelling, through history-writing, cross-referencing, footnoting, repeating. They ascend in acts of translation and misunderstanding. If to translate is to carry words from one language into another, it is also “to carry or convey to heaven without death.” Gods are made when language goes beyond its intentions. Occasionally, a god is born out of an excess of love. As the third-century theologian Origen wrote, in his commentary on the Song of Songs, “It should be known that it is impossible for human nature not always to love something.” It is also impossible for human nature not to love too much.

It may be that the surest way to find out what it means to be human is to ask what it means to be inadvertently, unwittingly, ingloriously divine. (12).

Although she does not mention the concept by name, her analysis of divinity maps onto the heuristic distinction between immanence and transcendence, as formulated by scholars like Karl Jaspers, Robert Bellah, and Alan Strathern most recently. According to this school of thought, divinity is either a matter of disenchantment and abstract belief or “faith” in a deity not of this world (transcendence) or of ritual exchange and knowledge of a non-ordinary presence or metaperson in this world (immanence). In those cultural systems which we have “etically” deemed immanent religions—among them the non-European peoples studied by Della Subin—to deny the divinity before one’s eyes is to deny the ground beneath one’s feet. The instances of divinization here thus happen organically through sequences of “accidents” or the unfolding of a cultural logic rather than through consciously planned or directed efforts.

To outline the cultural logic of Europeans and its role in the book’s case studies, Della Subin describes the impact of scholars like Max Muller, Max Weber, James Frazer, and Sigmund Freud upon the colonial-era development of religion and world religions as analytical categories. She further explores the link between Western colonizers’ conception of religion and exploitation, pointing toward genocides in the Americas, the violent aftermath of the 1947 partition of South Asia, and the rise of Hindu nationalism as at least partially the results of the imposition of Western conceptualizations of identity: race and non-Christian religion meld into a super-category for classifying peoples, and this new super-category then supersedes all other elements of identity. These subjects feed into the author’s understanding of how Europeans became accidental gods willing to use their newfound divinity to exploitative ends. The full effect of that exploitation is best brought out in the third part of the book, where she transitions from speaking about individual deifications of white Europeans by indigenous cultures to the glorification of the white race itself—the “deification of whiteness”—by the Europeans themselves.

Created in the colonial crucible, the deification of whiteness resulted from Europeans, whether British theosophists or Spanish colonizers, theorizing that non-white peoples were soteriologically inferior. In this view, only whites could be children of Adam, and thus fully capable of receiving God’s grace. Other races then belonged to a lesser genealogy, truly another species. Even when non-whites would convert to Christianity, their conversion would often be considered suspect because their physiology precludes them from the peak of religious thought. Pure monotheism is only for the whites, and divinity is in the Aryan DNA waiting to be brought out through purification. Quoting Colin Kidd, Della Subin declares that “religion [in the colonial period] had become an ‘epiphenomenon of race’.” She concludes with a suggestive section on how global society might go about killing the god of whiteness, although she does not advocate a specific plan of action, emphasizing the scope and difficulty of the problem.

. . .

Reading Accidental Gods, I appreciated the author’s brisk yet helpful summaries of the intellectual history of European theories of religion. They would work well as course materials for introductory classes, but with a necessary caveat. In giving her history of the idea of religion, she omits—as others have done before her—pre-modern, pre-colonial, and non-European instances of comparative religion, which necessitated the existence of religious identity as a category of social belonging. The author does mention the Mughal Emperor Akbar’s devotional cult, the so-called tawhid-i ilahi (“Divine Unity”), and his policy sulh-i kull (“Peace with all” religions) as pre-colonial instances of specifically religious tolerance but does not consider how this might complicate the Euro-centric narrative which holds that non-European peoples did not come up with abstract conceptualizations of religion and even of “world religions” prior to colonial intervention. Akbar’s policies would have been nonsensical without the social fact of different religious communities in South Asia: why would Hindus and Muslims need to be made to get along with each other if there were no distinct religious groups who did not see themselves as such? As recent research has shown, Sulh-i kull was meant to equally subjugate all religious communities to the emperor such that one could not have the power to persecute another.

But even the “early modern” Mughals did not develop this policy out of thin air; rather they innovated upon the policies of their ancestors, the Mongols, another non-Western empire that predated the Mughals by more than three centuries. When the Mongols conquered most of the Islamic world as well as China and other regions of Asia, they treated Islam as just one more religious community subject to the Khan, whom Eternal Heaven had ordained as sovereign over the whole world and its peoples. The Mongols, as it happened, also tended to conflate religious and ethnic identity. All of this galvanized a new search for religious identity and reconceptualization of the category of religion among Muslims who had lost their position at the top of the religious hierarchy. In this historical dynamic, Europeans are notably absent. Perhaps it would be more fitting, then, to associate the rationalization of religious identity with imperial structures, regardless of their geographical origin.

Specialists in religious studies may also object to Della Subin’s rather loose application of the idea of deification. She does not provide a theoretical framework to cover all of her case studies. In one sense, this allows for flexibility such that her study can cover Douglas MacArthur’s deification by Filipinos as well as the deification of whiteness more broadly. The first example is a person and the latter is an abstract concept. These instances only share two general commonalities: 1) that both occurred mostly through “accident” rather than through directed effort and 2) that both necessarily required the adoration of colonized peoples who did not share the European Christian perspective on the nature of religion. These two principles are not succinctly delineated in the book. In my view, this is a matter of genre and audience: Accidental Gods is a history aimed toward the general public, not a social-scientific study for specialists. As such, while she may give an historical account of social scientists’ development of theories of religion, she does not use social-scientific methods or even detailed citations as academic historians would. Some will see this as a lack of rigor, but creatively arranged historical data in a well-composed narrative can provoke the reader to think about things in a new, beneficial way.

Overall, Accidental Gods successfully incites the reader to consider the nature of godmen, the source of their power, and that power’s relationship to the world today, all while reaching literary heights that academic writing often shies away from. Religious studies scholars and general audiences interested in the historical interplay of religions and systems of domination will find much of value here. Lastly, Accidental Gods could serve as introductory course material because it offers a readable and socially-conscious summary of the early history of religious studies and its relationship to race and colonialism.

About the Reviewer:

Christian Blake Pye is a PhD candidate in Religious Studies. He specializes in the political history of medieval and early modern Islam, the Persianate world, Sufism, and Islamic sainthood. His dissertation addresses the development of the Andalusian Sufi Ibn ‘Arabi’s philosophy and its political reception as an epistemology which disrupts exclusivist claims to religious truth.

About the Author:

Anna Della Subin is a senior editor at the journal Bidoun. She is also a prolific essayist and independent scholar, with her work having appeared in the New York Times and Harper’s magazine, among other publications. She studied the history of religion at Harvard University’s Divinity School. Her personal website is http://annadellasubin.com.