by Marina Schneider

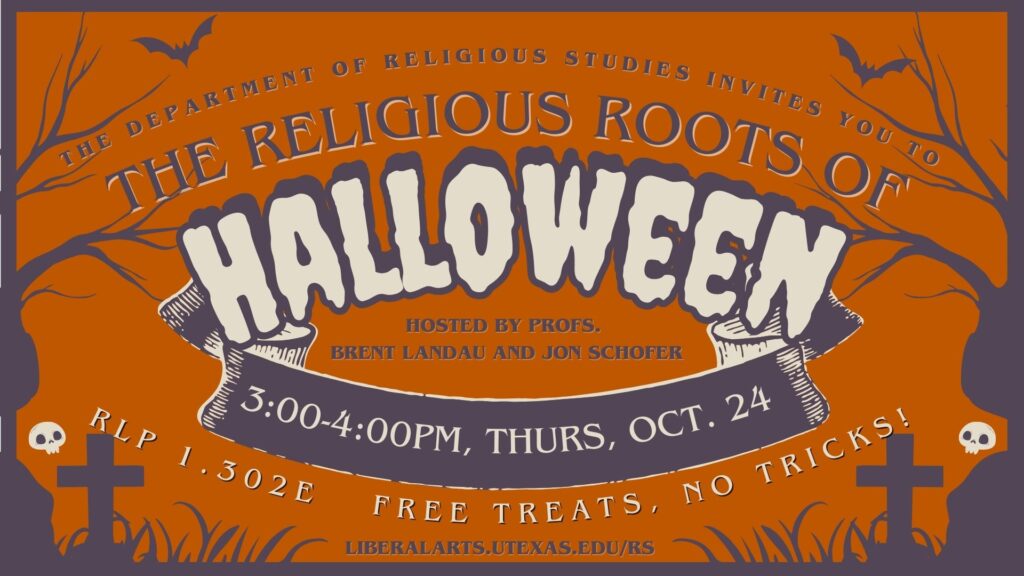

On Wednesday, October 24, Dr. Brent Landau and Dr. Jon Schofer delivered a joint lecture to a packed conference room of undergrads—crossed-legged-on-the-floor-room only!

Doctors Landau and Schofer took two differing but complementary approaches to discussing the potential roots of Halloween. Dr. Landau sought to explain why we have a spooky season. And for that matter, why do we even have seasons? Dr. Schofer then inquired into how we know about festivals in the past and the role of holidays in Roman, Jewish, and early Christian culture.

Bringing in content from his UGS course, Religion and Outer Space, Dr. Landau explained that the occurrence of seasons is actually quite rare in our solar system. The only reason the earth has seasons is due to a proto-planet crashing into the earth 4.5 billion years ago, causing the Earth to be tilted at a twenty-three-and-a-half-degree angle. The earth’s tilted axis is why we have shorter and longer days and nights during the year. In the northern hemisphere, the nights get longer between the fall equinox and winter solstice. The extended darkness of night creates a “spooky” season, during which various holidays in the autumn may have sprung up to make the growing darkness more bearable.

One such holiday was Samhain among the Celts in Ireland. Possibly the Celtic New Year, Samhain was a day when the boundary between the living and the dead was thought to be more permeable. It was believed that on this day the dead could take the form of nocturnal animals, so people would put out offerings of food and may have dressed up as the dead. In the 8th or 9th century, as northern Europe became Christianized, the Church decided to move All-Saints Day from May 13th to November 1st, the same day as Samhain.

Dr. Schofer’s lecture then introduced students to the writings of Asterius of Amasea, who, in circa 400 C.E., composed sermons condemning activities from the Roman festival of Kalends; this may have had some remarkable similarities to trick or treating. For example, Asterius complains in his sermon, “And these mendicants going from door to door follow one after another, and, until late in the evening, there is no relief from this nuisance.” Based on this complaint, scholars can theorize that Kalends involved a tradition of going door to door as modern-day trick or treating does. Through the writings of Asterius of Amasea, Dr. Schofer showed students what primary sources can tell us about what people may have been doing in the past.

The second part of Dr. Schofer’s lecture placed holidays in the Roman, Jewish, and early Christian context of the late antique world. The Roman festival Kalends involved members of the army and senate swearing an oath of allegiance to the emperor, as well as public rites. In the 4th century, Kalends celebrations spread across the empire. Since Kalends took place near the winter solstice, it competed with other important Christian and Jewish festivals. In the Jewish calendar, the holidays of Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, and Sukkot all occur in the fall, marking important moments in the Jewish calendar found in Leviticus.

The condemnation of Kalends in Asterius’s writings, and restrictions placed on Jewish participation found in the Babylonian Talmud, tell us about how religious distinctions were formed in the Late Antique world. Dr. Schofer closed his portion of the talk by noting that, as scholars, it’s our job to adjudicate between the values of the critic and the practices of those taking part in the festival.

Overall, this was a fun and informative lecture that invited curiosity into the historical and cultural origins of Halloween, giving students a peak at the topics a Religious Studies major could pursue.

Marina Schneider is a PhD student in the Department of Religious Studies at UT. Her research focuses on religion and the material culture of Medieval Spain.