By Marina Schneider

Rather than a comprehensive review, I have instead highlighted some of the arguments made in Adam Jasienski’s book with the hope of pointing out some of the ways this study could enrich religious studies as well as how some of the arguments would have benefited from interdisciplinary engagement with religious studies.

In his book Praying to Portraits: Audience, Identity, and the Inquisition in the Early Modern Hispanic World (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2023), Adam Jasienski seeks to elucidate some of the ambiguity surrounding early modern portraiture. In the interest of inclusion and capturing broader contexts, his text looks at artistic examples from mainland Spain as well as from the Spanish colonies in the Americas. The central thesis of Jasienski’s book is that any early modern portrait had the potential to become a sacred image (2). The ability for portraits to move between sacred to profane or profane to sacred made them flexible image types that challenge the supposition that portraits were “harbingers of secular modernity and autonomous selfhood” (4). Jasienski contends that in contrast to being emblems of secularity, portraits in the early modern Hispanic world played an important role in knowing, contemplating, and experiencing the divine.

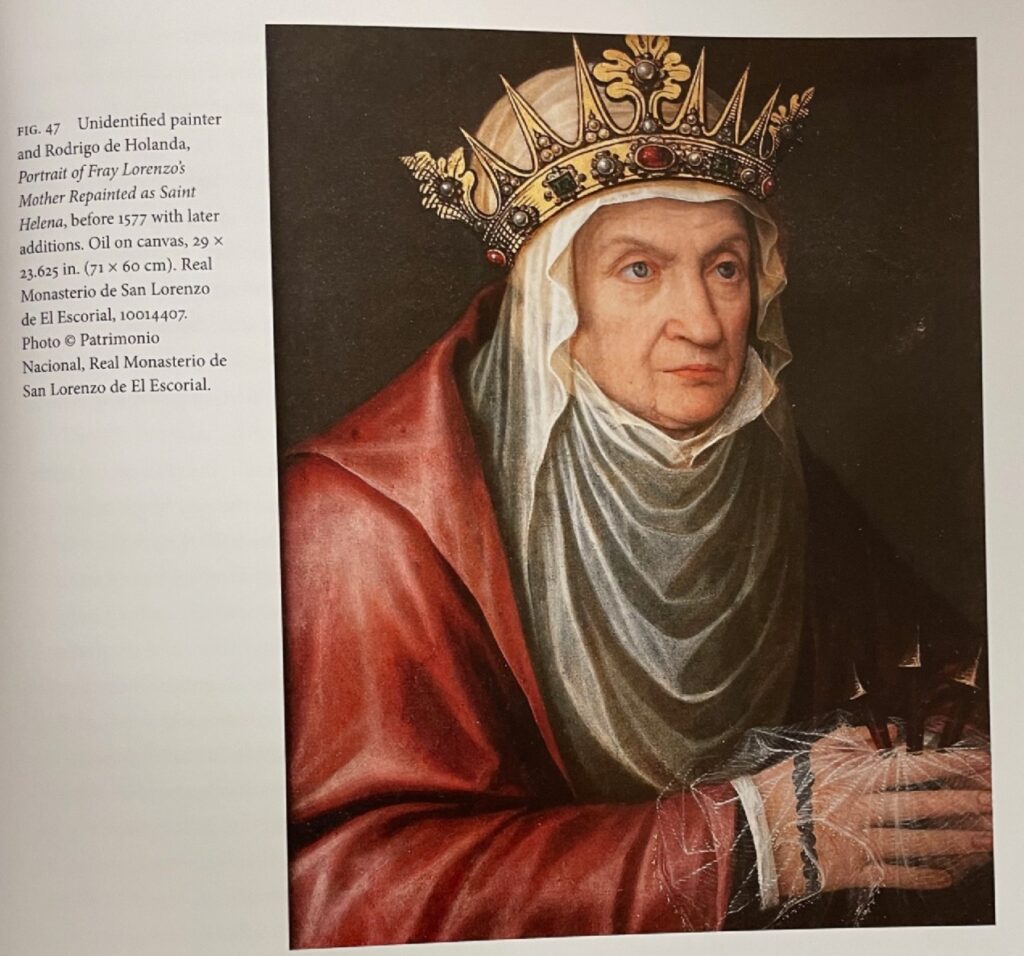

Chapter 3 is the strongest section of the book. In this portion, Jasienski outlines the potential reuses for portraits that no longer held significance for the viewer. When portraits were no longer recognized by anyone in the community, the author notes that they could be repainted to serve a religious function. The example the author examines is a portrait of the mother of a Friar Lorenzo, that after his death was ordered by King Phillip II to be changed into the image of Saint Helena (98). While the portrait of the woman was preserved, attributes of the saint were added, such as a crown, veil, and nails of the true cross in order to transform the portrait into an image of the saint. The reuse of portraits that could no longer be identified is a significant contribution to the field. While many scholars in religious studies focus on textual sources, this chapter engages with the material-based questions at the core of art history. This chapter prompts further reflection about the ways material culture can take on new meanings and interpretations over time. For religious studies, it may provide additional avenues for understanding shifts in religious practices over time such as the reinterpretation of or reengagement with textual sources.

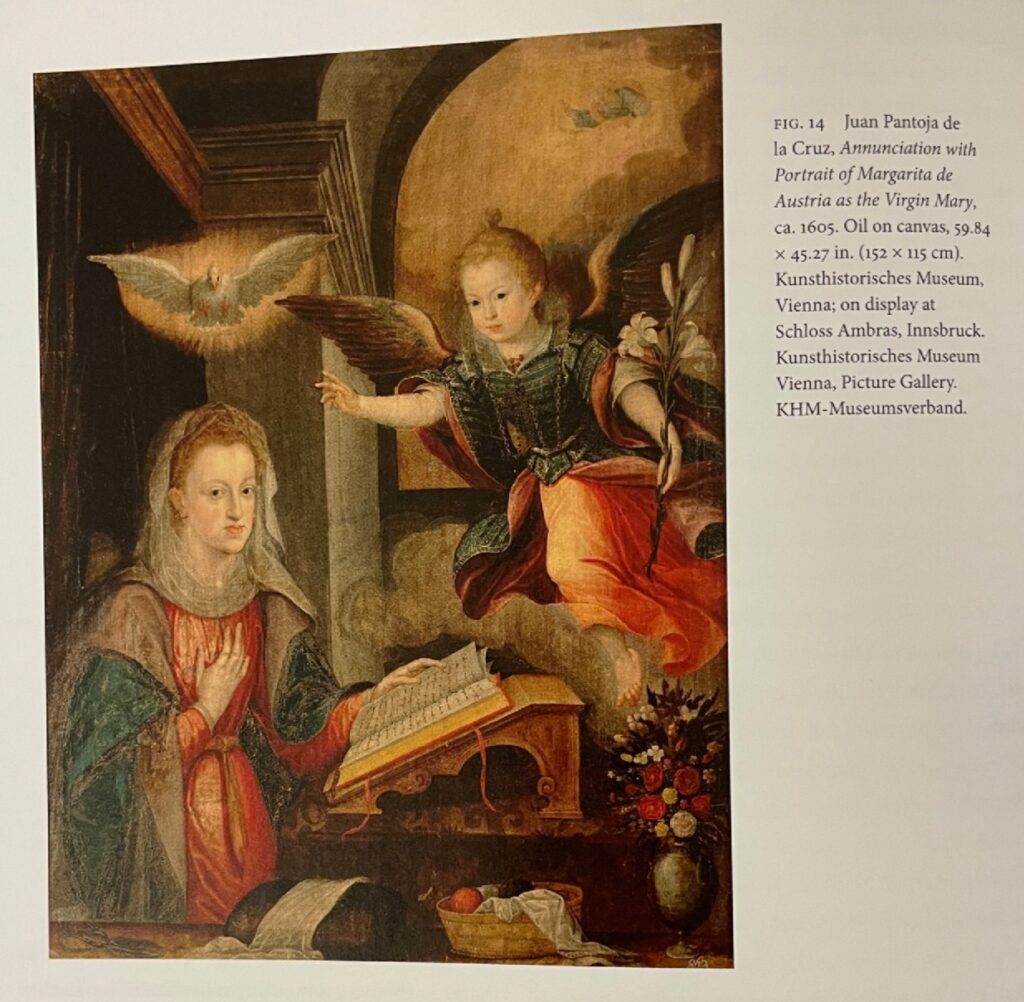

In the first chapter, Jasienski considers portraits of royal women, like Annunciation with Portraits of Margarita de Austria as the Virgin Mary, created by Juan Pantoja de la Cruz in 1605 (above). Jasienski notes that this portrait has been previously interpreted as visual evidence for a monarch’s reign as divinely sanctioned. In contrast, Jasienski follows the argument that unlike its European counterparts, the Spanish monarchy was not sacred, due to not following the same rituals or wearing the trappings of power such as crown and scepter (25). The painting shows the queen Margarita of Austria (wife of Phillip III) and her daughter Ana enacting the scene of the annunciation with Margarita as the Virgin and Ana as the Archangel Gabriel. In order to explain the portrait of the Queen as the Virgin as well as other analogous portraits produced around the same time, Jasienski argues that the portraits were produced for personal devotion, specifically the constant labor needed to dismantle selfhood. The idea being, only after dismantling her own selfhood could the queen look at the portrait of herself and see the Virgin (32). The process Jasienski believes the queen went through, in order to dismantle her sense of self, involved meditative practices such as Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises administered by her Jesuit confessor, Richard Haller. “That Haller was a Jesuit is crucial here, she would have exposed Margarita to period forms of eschatologically motivated meditative practice, likely including Ignatius of Loyola’s Spiritual exercises…which announces that the goal is for the exercitant—or practitioner—to… ‘vanquish oneself’” (32). Although, as the authors states, there is no evidence that the queen undertook this exercise, there were arguments within the order about whether women could be administered the Exercises (32).

The analysis of royal women and meditative practices has some gaps. A factor that the author does not address in discussing the paintings’ role in personal devotion is the scale of the paintings. The canvases showing the queen in the role of the Virgin are quite large, around five feet by three feet or eight and a half feet by five and a half feet. If the portraits were meant to help the queen dismantle her own selfhood, why were they made so large? Later in the chapter, the author states that the paintings do not appear in the list of payments made to the artist, perhaps due to their unorthodox nature. If this is the case, and the portraits were made to assist in “moving from the limitations of her own self to the universality of the holy figure” (34-35) as St. Francis did in his contemplation and imitation of Christ, what is unorthodox or transgressive about them? Additional teasing out of specific contextual particularities would have strengthened this line of argumentation, and helped distinguish the ways various social strata engaged sacred portraiture.

Chapter four returns to the subject of royal portraiture, this time the king’s portrait. Jasienski views Hapsburg royal portraits as unrecognizable royal portraits, because they lack royal symbols to identify the monarch as a king such as crowns or scepters. While these portraits lacked specific symbols of royal power, they were strictly controlled. The author points to an example from 1633 when the royal artists Diego Velazquez and Vincente Carducho were ordered to evaluate portraits of the king and royal family in order get rid of depictions that did not meet the standards of royal representation. Of eighty-four paintings collected from studios around Madrid, only twelve were deemed to possess the requirements for representing royalty. (128) Like portraits of saints, textual sources described instances when viewers spontaneously recognized portraits of the king due to their majesty, treating them with the respect and ceremony dictated for royal images. The author draws attention to the fact that although royal portraiture looked like other portraits, it functioned like religious artworks. One example of this is that portraits of the king contained his essence so they could stand in for the king, such as in ceremonies in the Spanish colonies. Significantly, the overlap between royal and saintly portraiture sometimes caused friction between the monarchy and the Church. In the early modern period, royal portraits were displayed beneath dosel, a canopy or baldachin which in the medieval period were primarily used by church authorities. The way royal portraits were instructed to be displayed beneath framing devices such as dosels is nearly identical to the customs of display for sacred images.(137). One example of conflict that could erupt between the church and monarchy over the display of images is in 1666, when Quito Alonso de la Peña Montenegro wrote to the court in Madrid to address an accusation that he had inappropriately appeared beneath a baldachin during a bullfight (136). Who was allowed to use dosels or portray themselves in certain ways was a site ripe for contestation. This is a chapter where the blending of royal, ecclesiastical, and saintly symbolism would have benefitted from engaging with literature in religious studies. Specifically, I think religious studies would give art historians new ways of addressing the complex negotiations of power and authority in both religious and political contexts.

In each of Jasienski’s chapters he considers multiple categories of images in order to showcase the variety of sources and interpretations available to the scholar. However, the way the various sources were presented at times blended and conflated the images without always adequately drawing distinctions between the different social contexts for which each could have been produced. While his argument that early modern portraits served various functions is important, the execution of the argument at times obscured nuance; the author also seemed to contradict himself. For example, although the author stresses that the Spanish monarchy was not sacred, he notes multiple examples where royal images took on the trappings of sacredness, but does not consider this a challenge to the supposed secular nature of the monarchy. While the author seeks to understand sacred portraiture in the early modern Hispanic world, for this reviewer there was not enough separation between cases to adequately parse out the contextual specifics of the varied uses for portraiture in the early modern Hispanic world.

Marina Schneider is a PhD student in the Department of Religious Studies at UT. Her research focuses on religion and the material culture of Medieval Spain.