By Molly Wells

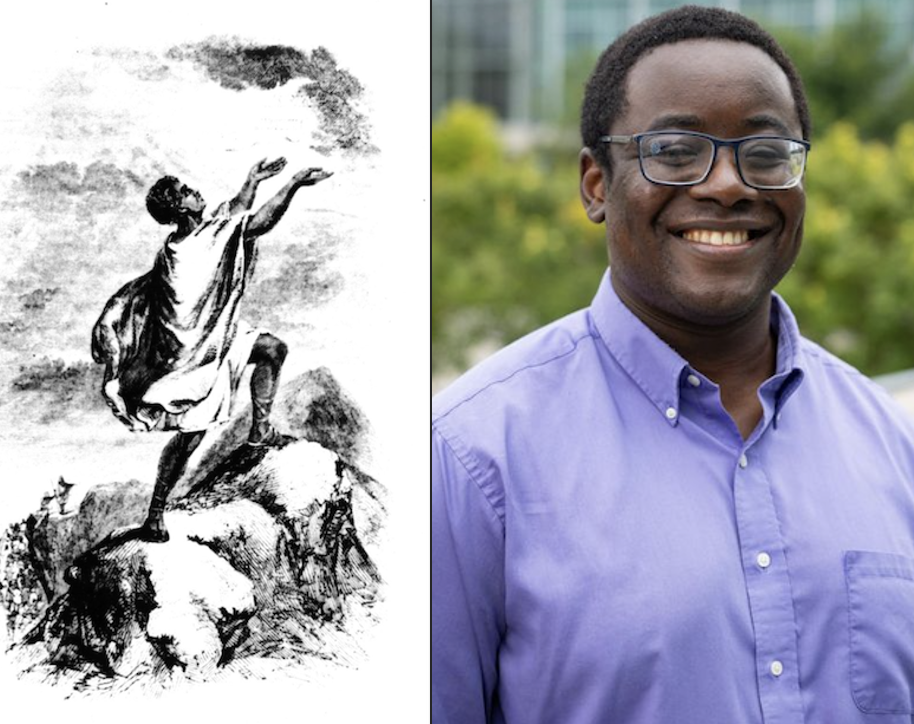

On Monday, October 20th, the Department of Religious Studies hosted Dr. Toni Alimi for its first colloquium of the fall semester. Dr. Alimi is an assistant professor in the Department of Religion and the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University, and his recent book, Slaves of God: Augustine and Other Romans on Religion and Politics, was published in 2024 by Princeton University Press.

Alimi has three main goals in Slaves of God. First, he explains and elucidates Augustine’s account of chattel slavery specifically. Second, he interrogates the connections between conceptions of chattel slavery and conceptions of universal slavery to God in Roman Christian theology. Finally, Alimi seeks to understand and connect Augustine’s ideas of slavery to his broader thought. In order to achieve these goals, Alimi considers Roman thinkers outside of Augustine, such as Cicero, Seneca, and Lactantius. Alimi convincingly argues that these three figures greatly influenced Augustine’s own conceptions of slavery. For example, Cicero believed slavery wasn’t inherently wrong; Seneca believed that slavery could benefit the slave; Lactantius believed that all humans were slaves to God. Augustine worked with these three main principles to come to his own conclusions.

In the book, Alimi’s argument is that Augustine used the concept of universal slavery to God to justify chattel slavery, writing “chattel slavery is legitimated by slavery to God, which is in many ways [his] fundamental description of the divine-human relationship” (257). Furthermore, Alimi shows that Augustine’s stance on slavery is inextricable from his broader theology. Alimi’s current project expands the inquiry into Augustine’s relationship with slavery to reconsider his attitude towards natural slavery. This current project, building upon the research laid out in his book, was the focus of the presentation at the colloquium.

Alimi began his talk clarifying the definition of a “natural slave.” A natural slave, he explained, is “someone permissibly enslaved (enslaveable) because nature designates her a slave” (quote from the handout provided during the colloquium). Thus, someone who condones natural slavery believes that some humans are born naturally enslaveable. Alimi explained that most scholars agree that Augustine condemned natural slavery theses, because, he wrote, “For we recognize it is on sinners that the condition of slavery is justly imposed. That is why we do not read of any slave in Scripture until the just man Noah punished his son’s sin with this designation until the just man Noah punished his son’s sin with this designation” (City of God 19.15, provided by Alimi, translation from the New City series). Alimi contends, however, that when we look more closely, Augustine considered four different natural slavery hypotheses, of which he affirmed three and rejected one.

Alimi’s criteria for a natural slavery thesis are that they all purport the following: “1) nature designates slaves; 2) people so designated merit being enslaved, 3) regardless of their actions” (quote from the handout provided during the colloquium). The first natural slavery thesis that Alimi argues Augustine affirmed is that all humans are slaves to God by nature of their creation. In other words, because all humans are created, they are therefore enslaveable by God, regardless of their actions. The second thesis is that some humans are naturally enslavable to other humans (Alimi calls this “original chattel”). This is the thesis that Augustine denied (as visible in the quote from City of God above). The third thesis claims that sinful nature appoints humans as slaves to sin, regardless of their actions. The fourth thesis, which Alimi calls “Fallen Chattel,” puts forth that sinful nature appoints some humans as slaves to other humans, regardless of their actions.

Alimi calls on Augustinian scholars and scholars of religion in antiquity to reconsider their dismissal of Augustine’s affirmation of natural slavery. By breaking the concept of natural slavery into four different hypotheses, Alimi expands our understanding of the phenomenon and shows how Augustine interacted with it – as he affirmed three of the four hypotheses. The next step for Alimi in this project, as he described it, involves deciphering the relationship between Augustinian theology, and Christian theology more broadly, and the colonial Atlantic slave trade. Part of the justification for chattel slavery initially involved the argument that it could help bring Christianity to non-Christians. Alimi points out, however, that slaves could convert – dismantling the argument for their enslaveability. Thus, the determining factor for enslaveability shifted from religion to race.

Alimi’s contribution with both his book and his subsequent intellectual projects challenges the status quo of Augustinian studies. Furthermore, it contributes to the field of religious studies more broadly as he grapples with the role religion plays in broader social and cultural phenomena such as slavery, citizenship, and categories of race. Alimi extracts Augustine’s theory of religion to show how closely intertwined it is with his ideas of slavery. This theory of religion has stood the test of time and is still relevant in theological circles today. Alimi’s intervention points out some of the uncomfortable consequences of Augustine’s legacy as well as the consequences of the field’s avoidance, or dismissal, of the topic. The department would like to thank Dr. Alimi for joining us for a stimulating discussion.

Molly Wells is a PhD student in the Religious Studies Department at UT. Her research focuses on medieval Islamic philosophy.