Featured Image [above]: “The Art and Mystery of Printing Emblematically Displayed,” satirical illustration of a printing house in three parts, from the Grub Street Journal, No. 147, 26 October 1732

Jacob Tonson (1655-1737), publisher

Conveying his status as an idealized publisher, Jacob Tonson’s portrait showcases a “plump, well-formed, middle-aged man, with jutting jaw (a mark of independence, even pugnaciousness?)” (Walker 424). Rightly displaying this reputation, self-made Tonson was apprenticed to the stationer Thomas Basset and set up his own publishing firm in 1678 after completing his apprenticeship (MacKenzie). In 1679, in the wake of publishing anonymous, inconspicuous works in partnership with other booksellers, Tonson began to publish the works of John Dryden and soon became Dryden’s chief publisher. After his first distinguished publication, Absalom and Achitophel (1681), Tonson bought the rights to Dryden’s earlier works and published a variety of the most significant writers of the time (MacKenzie). Particularly, Tonson issued John Dryden’s translation of Virgil (1697) and his anthologies of poetry (from 1684), poetry by Alexander Pope (1709), and numerous pieces by Joseph Addison (Encyclopædia Britannica).

As a young entrepreneur, Jacob Tonson bought half of the rights to Milton’s Paradise Lost from the printer Brabazon Aylmer. In 1688, Tonson and Aylmer “printed a folio-size fourth edition of the epic” with “illustrations, a frontispiece portrait of Milton, and an epigram by Dryden in which Milton is said to be the union of Homer and Virgil” (Kerrigan et al. 253). In 1691, Jacob Tonson purchased Aylmer’s half of the poem and the manuscript of Book I (Kerrigan et al. 253) Throughout the eighteenth century, Tonson and his family would print countless works by Milton in various configurations (Kerrigan et al. 253). Tonson had his own portrait, in which he holds a copy of his edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost, engraved by John Faber.

Tonson later became known for his “beautiful editions of Shakespeare and Spenser” (Kerrigan et al. 253). In 1728, Alexander Pope mentioned Tonson favorably in his first book of The Dunciad. Pope’s flattering reference to Tonson “Till genial Jacob, or a warm third day,” referring to the third day of a theatrical production when the writers get paid as akin to Genesis in Milton’s version in Paradise Lost (Dunciad, 354). Pope identifies Tonson as a publisher who doesn’t base his career on money but passion. In The correspondence of Alexander Pope, Pope mentions visiting Tonson at The Hazels, inviting his friend the earl of Oxford, and promising that he would find Tonson to be “the perfect Image & Likeness of Bayle’s Dictionary; so full of Matter, Secret History, & Wit & Spirit” (Correspondence, 176).

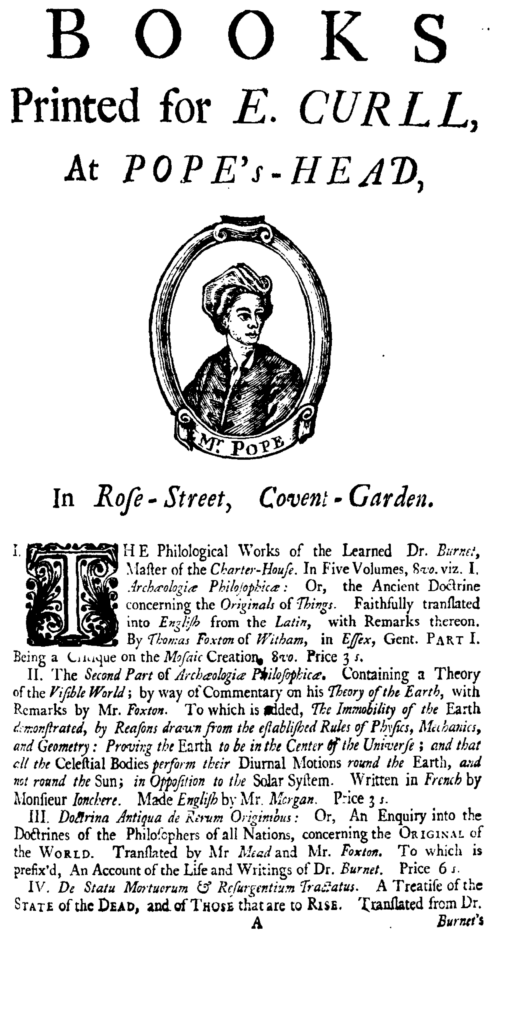

Edmund Curll (c. 1675-1747), bookseller and publisher

Curll established his place in history as a bookseller for whom success and scandal went hand in hand. He sold a wide variety of works, including translations, poetry, fiction, divinity, medicine, and antiquarian material, all at the price of one or two shillings. At a time when books were considered a luxury, Curll’s relatively low prices “help[ed] to create a new lower end for the book market” (MacKenzie). Curll also promoted many works written by women, which was innovative for the early 18th century.

Curll had many feuds throughout his career, the most famous being his lifelong rivalry with Alexander Pope. Their feud began after Curll published Pope’s “Court Poems” without permission in 1716. Pope and his publisher, Lintot, then invited Curll to Swan Tavern on Fleet Street where Pope laced Curll’s drink with a powerful emetic, making him violently ill. Pope published two pamphlets recounting the interaction, satirically reporting Curll as dead. Curll responded by printing two works that attacked Pope’s appearance and religion. The two continued to publicly defame one another for the rest of their careers.

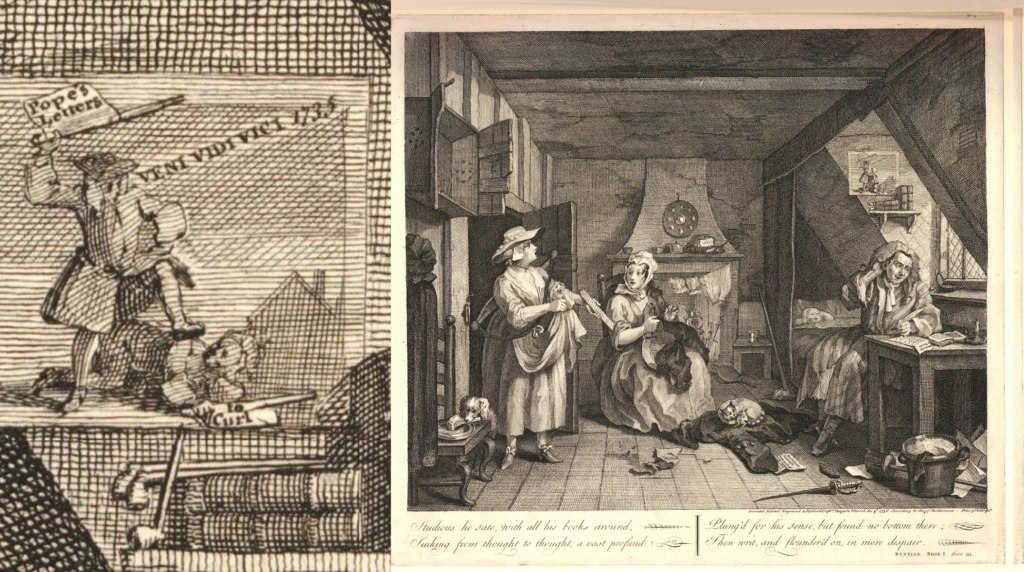

The hallmark of their feud occurred when Pope featured Curll in The Dunciad, where he slips in his wife’s waste and receives aid from the Goddess of the Sewer: “Oft had the Goddess heard her servant’s call, / From her black grottos near the Temple-wall. . . / Renew’d by ordure’s sympathetic force, / As oil’d with magic juices for the course” (Pope, 97-104). The Dunciad also references the incident in which Westminster scholars “forced [Curll] down on his knees and made [him] beg for forgiveness” before whipping him and tossing him in a blanket as punishment for publishing an unauthorized account of the trial of the earl of Wintoun: “Himself among the story’d chiefs he spies, / As from the blanket high in air he flies” (Pope, 151-152). In response to The Dunciad, Curll published a pirated version of the poem, a series of keys explaining its allusions, and a series of mocking poems in reply.

The rivalry between the two men became an accidental partnership, as both men expanded their readership through their attacks on one another. Their names became so inseparable that Curll eventually changed his shop sign, from the generically genteel Dial and Bible to the provocative Pope’s head. Although Curll’s name was tarnished by his many distasteful publications and public feuds, his popularity grew along with his reputation.

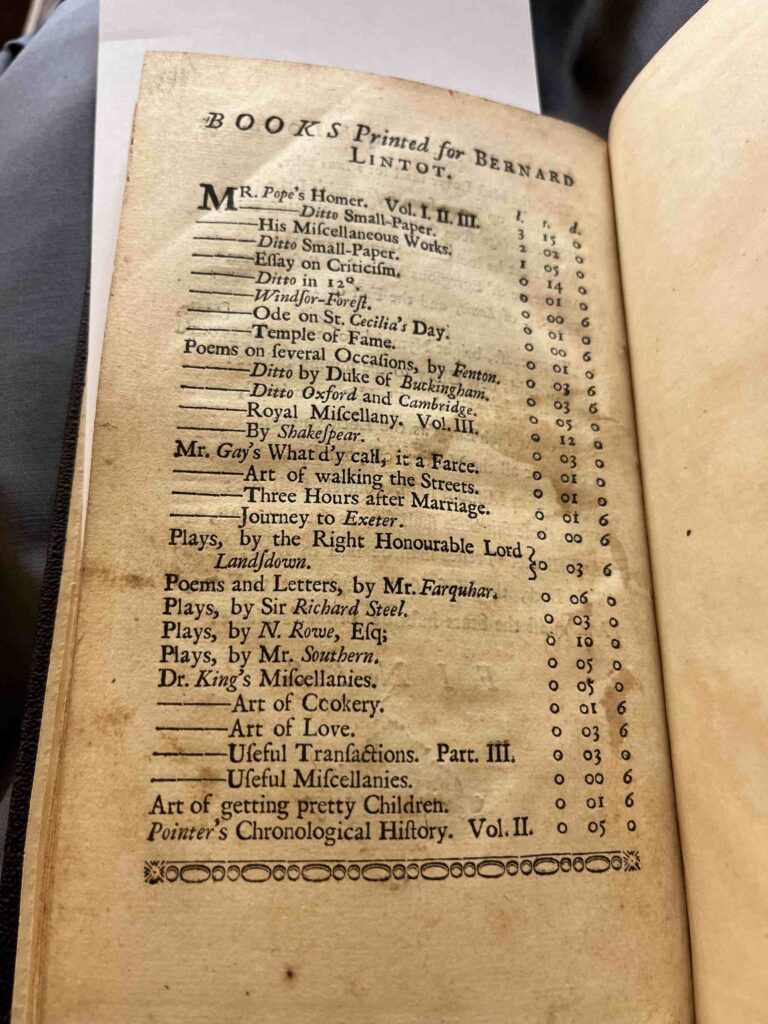

Barnaby Bernard Lintot (1675-1736), bookseller and publisher

Lintot published several members of the Scriblerus Club and is most often recognized for distributing Alexander Pope’s The Iliad through an innovative subscription system. The highly successful method was Lintot’s idea, and he networked to collect signatures (Ryskamp).

In 1724, Pope betrayed Lintot by asking his rival, Jacob Tonson, to publish The Odyssey. Lintot retaliated with Proposals by Bernard Lintot, for his own Benefit in 1725 (Johnson). In return, Pope referenced him in The Dunciad three years later. He mocked Lintot’s body, comparing him to a waddling chicken, and depicted him losing a contest to Tonson. Pope exaggerates, “Swift as a bard the bailiff leaves behind, / He left huge Lintot, and out-stript the wind. / As when a dab-chick waddles thro’ the copse, / On feet and wings, and flies, and wades, and hops; / So lab’ring on, with shoulders, hands, and head, / Wide as a windmill all his figure spread, / With legs expanded Bernard urg’d the race, / And seem’d to emulate great Jacob’s pace” (The Dunciad Book II Lines 59–64)

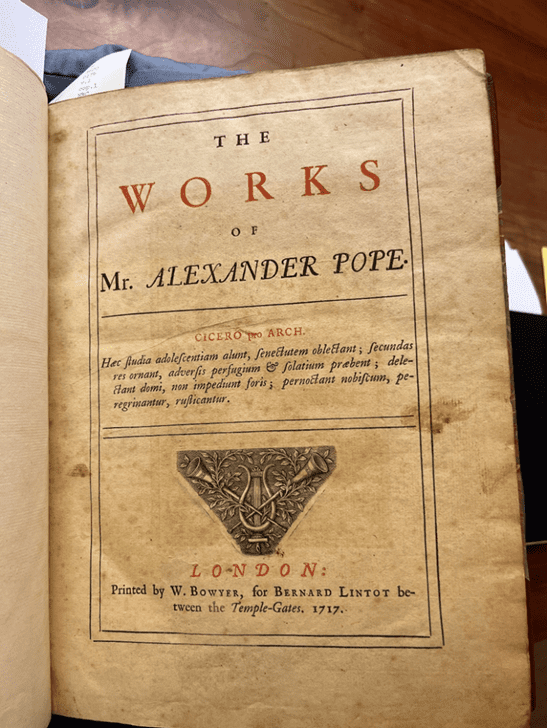

Not only is Pope’s portrayal of Lintot humiliating and grotesque, but by including him in The Dunciad, Pope implies that Lintot is partially responsible for the pervasive dullness in the literary sphere, and that he is chasing wealth and fame rather than literary excellence (Watt). In the “Verses to be prefix’d before Bernard Lintot’s New Miscellany,” Pope parodies what he perceives as Lintot’s self-importance, which manifests in bold capitalization and red ink. Pope declares, “I, for my part, admire Lintottus. – / His Character’s beyond Compare, / Like his own Person, large and fair. / They print their Names in Letters small, / But LINTOT stands in Capital: / Author and he, with equal Grace, / Appear, and stare you in the Face… / Their Books are useful but to few, / A scholar, or a Wit or two: / Lintot’s for gen’ral Use are fit; / For some Folks read, but all Folks sh-” (“Verses to be prefix’d before Bernard Lintot’s New Miscellany” Lines 6-12 and 27-30)

In the Verses, Pope calls Lintot useless and egotistical. The suffix “-us” in Lintottus could either be a sign of respect or a weapon of satire, but in this context, “Lintottus” is used derisively. Pope wrote the Verses in 1717 or earlier, which predates the start of their feud and thus reveals that Pope had been harboring resentment for years beforehand.

Despite Lintot’s involvement in petty squabbles, his legacy has remained formidable (Watt). The majority of people remember him for establishing The Iliad’s subscription system, which diminished class divides in literature, boosted Pope’s career, and popularized higher pay and autonomy of authors.

Works Cited

Curll, Edmund. Books printed for E. Curll, at Pope’s-Head, in Rose-Street, Covent-Garden. N.p.,[1735]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0118263669/ECCO?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=81aa35c6&pg=1. Accessed 3 Apr. 2023.

Faber, John, 1695?-1756, printmaker., and Kneller, Godfrey, Sir, 1646-1723, artist. Mr. Jacob Tonson [Graphic] / G. Kneller Bart. Pix. ; I. Faber Fecit 1733. 1821]. Folger Shakespeare Library, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.25238707.

“Head-Piece to Book I of Pope’s ‘The Dunciad’.” Works of Art | RA Collection | Royal Academy of Arts, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/head-piece-to-book-i-of-popes-the-dunciad.

Hogarth, William. The Distressed Poet. The British Museum, 1737, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_S-2-55.

Johnson, Samuel. “The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Samuel Johnson’s ‘Lives of the Poets’.” Project Gutenberg, 8 Jan. 2008.

Lynch, Kathleen M. Jacob Tonson: Kit-Cat Publisher. Univ. of Tennessee Press, 1971.

MacKenzie, Raymond N. “Curll, Edmund (d. 1747), bookseller.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 03. Oxford University Press.

MacKenzie, Raymond N. “Tonson, Jacob, the elder.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 Sept. 2004.

Milton, John, et al. The Complete Poetry and Essential Prose of John Milton. Modern Library, 2007.

Pope, Alexander. The Dunciad. Edited by John Butt, Yale University Press, 1963.

Pope. The Correspondence of Alexander Pope. Vol. 3. N.p., 1956.

Publisher: Jacob Tonson, the Elder (British, London 1655-1736 Barn Elms, Surrey), et al. Shakespeare’s Head Emblem. Wood cut and letterpress, 1735. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.27395381.

Ryskamp, Charles. “‘Epigrams I More Especially Delight In’: The Receipts for Pope’s ‘Iliad.’” The Princeton University Library Chronicle, vol. 24, no. 1, 1962, pp. 36–38. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/26402712. Accessed 3 Mar. 2023.

“The Dunciad .” The Poems of Alexander Pope: A One-Volume Edition of the Twickenham Text with Selected Annotations, by Alexander Pope and John Butt, Yale University Press, 1973, pp. 349–370.

The Editors of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, and Grace Young. “Jacob Tonson.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2022, www.britannica.com/biography/Jacob-Tonson.

Walker, Keith. “Publishing: Jacob Tonson, Bookseller.” The American Scholar, vol. 61, no. 3, 1992, pp. 424–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41212044.

Watt, Ian. “Publishers and Sinners: The Augustan View.” Studies in Bibliography, vol. 12, 1959, pp.3–20. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40371253. Accessed 1 Mar. 2023.