Top Image: A detail from the headpiece to the 1735 edition of Book III of The Dunciad, drawn by William Kent and engraved by Paul Fourdrinier. We interpret the monster as an image of Alexander Pope criticizing the writers featured below (Royal Academy of Arts).

Unfortunately, the following authors are remembered not for their literary contributions but as victims of The Dunciad’s cruelty. If the Scriblerian group threw shade, these writers caught the worst of it. Yet each made innovative and noteworthy contributions to so-called Grub Street.

Laurence Eusden (1688-1730), Poet Laureate

Born in 1688, Laurence Eusden served as Royal Poet Laureate from 1718 until his death in 1730. He was appointed Laureate by Thomas Pelham-Holles, Duke of Newcastle, whose good graces he earned by flattering his marriage to a Lady Henrietta Godolphin. His other works include Verses at the Last Publick Commencement at Cambridge, The Origin of the Knights of Bath, and a particularly flattering letter on the king’s ascension to the throne. He also translated and commented upon Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Joseph Addison’s Cato, and other works.

In the years leading up to his appointment, Eusden actively contributed to the literary scene, corresponding with authors such as Richard Bentley, Joseph Addison, and Richard Steele. Addison and Steele mention Eusden and his poetry in The Spectator and The Guardian, two early London newspapers. All four men, and indeed most of the other authors whom Eusden befriended, identified as Whigs, and that, along with associations to Addison, was enough to make Laurence Eusden a target of Alexander Pope’s Dunciad.

In The Dunciad, Eusden is lauded as an avatar of Dulness. Pope makes this connection by saying “And Eusden eke out Blackmore’s endless line,” and “Beneath his reign, shall Eusden wear the bays,” referring first to Richard Blackmore, another target of Pope’s satire. Pope also points to Eusden as the harbinger of a new “Saturnian,” or Lead Age (as compared to a Golden or Silver Age) (The Dunciad Variorum, Bk I, Ln 102, Bk. III line 319). In his footnotes, Pope writes, “Mr. Eusden was made Laureate for the same reason that Mr. Tibbald was made Hero of This Poem, because there was no better to be had” (footnote to Bk III, Ln 319). After Eusden’s death, Pope writes that he sleeps “Safe, where no Critics damn, no duns molest; Where wretched Withers, Ward, and Gildon rest,” referring to George Wither, Edward Ward, and Charles Gildon, all former satirists and writers, all deceased by 1731 (The Dunciad, Bk I, Lns 295-96).

Pope’s ire influenced opinions on Eusden for decades. Author Thomas Gray, in a letter to William Mason dated 1757, said that “Eusden was a person of great hopes in his youth, though at last he turned out a drunken parson” (Sambrook, Eusden, Laurence). As Eusden did not ever respond to attacks on his person or poetry, no information exists to prove Gray wrong, but historians postulate that such descriptions, along with Pope’s insults, were exaggerations that survived only because Eusden’s work was not notable enough to outshine such rumors. As such, Alexander Pope’s defamation preserves Eusden’s memory.

Eliza Haywood (c. 1693-1756), writer, actress, and publisher

Eliza Haywood, one of the most prominent and prolific writers of the eighteenth century, published more than 75 volumes of conduct literature, criticism, journalism, fiction, drama, translations, history, pseudo-memoirs, and parody. Haywood’s staggering canon contributed to the advent of the British novel and benefited from the rise in literacy. Mockingly dubbed “Ms. Novel” by Henry Fielding, Haywood’s amatory fiction drew the jealous eyes of her male contemporaries, notably Alexander Pope in The Dunciad. Despite this, Haywood’s work dominated bestseller lists throughout career, revolutionized Grubstreet print culture, and reshaped the role of satirist.

In 1728, Pope published the first installment of The Dunciad, a mock epic ridiculing London print culture. Throughout, Haywood’s role as novelist is associated with moral promiscuity. Martinus Scriblerus first singles her out as a “libelous novelist” in the preface. Eventually, Haywood and her works are offered as a prize in an opprobrious pissing contest (Pope). The game suggests a territorial claim to Haywood and emphasizes the two publishers’ mindless engagement with the print industry. Pope further insults Haywood as a something which pollutes London. In Pope’s first published footnote to the contest, Haywood is representative of the “shameless scribblers” of her sex as well as all authors of “libelous Memoirs and Novels” who transgress propriety. The note is remarkable for both its prejudice and its falsity: no “romans-á-clef” were attributed to Haywood at the time (Backschieder). While Pope’s ire might have in part been motivated by personal slights, such as Haywood’s well-publicized Whig sympathies or her attacks on Savage (a close associate of his), Haywood’s impressive literary presence may have caused anxiety about a female writer (and a novelist to boot) on the literary scene.

Modern critics assert that, rather than retreating from publishing after the attack, Haywood took advantage of a theatrical revival brought about by the popularity of The Beggar’s Opera. Haywood would also continue to offer political commentary in the experimental works Eovaai (1736) and The Invisible Spy (1754). Her ambitious novels are reminiscent of Scriblean satire in their indictment of public figures .

Haywood’s works survived both critical defamation and her own death in 1756. She remains one of the most revolutionary and successful writers in English.

Elkanah Settle (1648-1724), last of the City Poets

Elkanah Settle was a poet and playwright in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. His best known work is The Empress of Morocco (1673), a play that was artistically successful and a catalyst for his petty feud with John Dryden (Brown 13-15). After the publication of The Empress, in which the preface included nameless but clear insults to Dryden, the two writers bickered through a triad of Empress of Morocco rewrites.

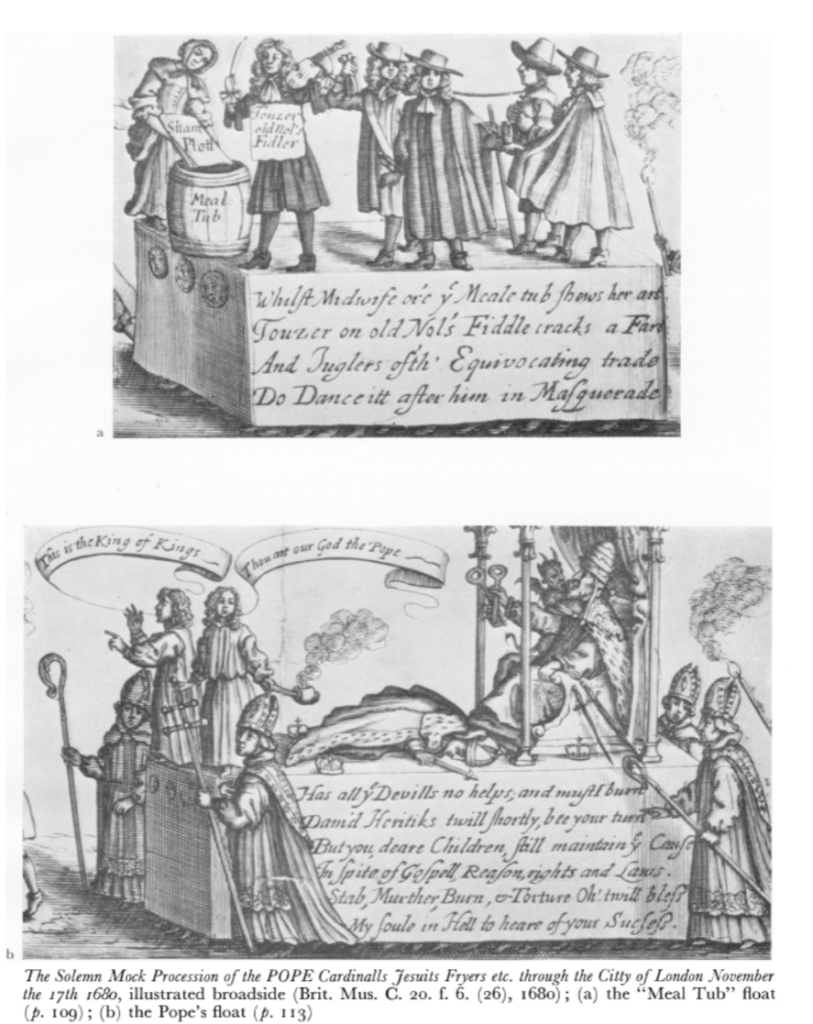

anti-catholic events in which statues and monuments of the pope were burned in a celebratory fashion. While the image above is not from Elkanah Settle, Settle spent his time as a Whig loyal to the Earl of Shaftesbury and managing these processions.

Beyond The Empress, Elkanah Settle’s writing was primarily political. However, due to constantly fluctuating party allegiances, his credibility and impact remained minimal. From 1679 to 1683, Settle wrote propaganda in support of the Whigs, denouncing potential catholic rulers and managing pope-burning pageants (See Fig. 1) (Brown). In 1683, Settle’s stance changed when, due to the financial insecurities of the Whig party, he turned Tory. Settle then produced two pieces, The Narrative and A Supplement to the Narrative (1683), to defend and gain support for his turnaround. The Tories, however, were not eager to have him. After the Tories’ economic success dwindled in 1688, Settle switched parties a third time and halted his political work.

In The Dunciad, Settle, like many, did not escape Pope’s wrath. Settle appears in the last book as a guiding spirit to Cibber, the hero of the satire. Settle takes Cibber to the Mount of Vision, where he explains the past, present, and future of Dullness’s empire. He then tells of his experiences, recalling, “long my party built on me their hopes, for writing pamphlets and for roasting popes, yet lo!… Reduced at last to hiss my own dragon” (Pope). Here, Pope comments on Settle’s political shifting, how his party “built on [him] their hopes,” only for him to fail them. Further, Settle “reduced at last to hiss [his] own dragon” refers to his real-world participation in the Bartholomew Fair, where Settle pretended to be a dragon in a cage. Settle was often ridiculed for his role in the fair, as the event was known for promoting drunkenness, prostitution, and disorder.

While his feud with John Dryden and his role in The Dunciad suggests Elkanah Settle was a literary failure, his career was anything but. Settle wrote 22 plays and dozens of poems, his tragedies were performed on stage with elaborately adorned sets (see Fig. 2 & 3), and his dramatic works proved monumental in the theatre of the Restoration era.

Nahum Tate (1652-1715), poet and lyricist

Nahum Tate was born in Ireland in 1652 and served as poet laureate of the United Kingdom for twenty-three years, from 1692 until his death in 1715 (Spencer 11, 15, 31). Tate created a variety of literature throughout his career, including The Second Part of Absalom and Achitophel, and the libretto for Henry Purcell’s operatic Dido and Aeneas (Spencer 15). While serving as poet laureate, Tate’s most significant work was his 1696 collaboration with Nicholas Brady on A New Version of the Psalms of David, a translation which churches used until the 19th century (Spencer). One of Tate’s hymns, “While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks by Night,” is still sung today (Spencer).

But Tate remains most famous for his 1681 adaptation of Shakespeare’s King Lear, which most notably gave the tragic work a happy ending (Spencer 68; British Library). Theatrical productions used Tate’s version for over 150 years, although it later received criticism for its alterations (British Library; Spencer 70).

In the later editions of The Dunciad, Alexander Pope condemns Tate to the Kingdom of Dulness for what Pope maintains is unimportant and non-influential work. Tate first appears in the 1742 edition of the mock epic when Pope writes: “She saw slow Phillips creep like Tate’s poor page” (Pope 442). The footnote for the line then adds, “Nahum Tate was poet laureate, a cold writer, of non invention; but sometimes translated tolerably when befriended by Mr. Dryden. In his second part of Absalom and Achitophel are above two hundred admirable lines together of that great hand, which strongly shine through the insipidity of the res” (Pope 442). Pope also criticizes Tate and the poet laureateship:

“O! Pass more innocent, in infant state,

To the mild limbo of our father Tate:

Or peaceably forgot, at once be blessed

In Shadwell’s bosom with eternal rest!” (Pope 451)

While unkind, Pope’s description of Tate in “mild limbo” is not an inaccurate reflection of Tate’s legacy. Pope was not Tate’s only critic, and his works later garnered such lackluster reception that critics devised the term “Tatefication” in the 1800s to describe the corruption or unfounded alterations of a translated work (Spencer 14). While the length and extent of his legacy remain minimal, Tate’s writings reflect important history, as they spanned the reign of five monarchs and resulted in works that made their mark on theater, hymns, the art of translation, and poetry (Spencer 15).

Works Cited:

Anonymous. “The Stage’s Glory”. BritishMuseum, circa 1731, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1868-0808-3540.

Brown, Frank Clyde. Elkanah Settle, His Life and Works, by F.C. Brown. The University of Chicago press, 1970.

“David Garrick’s Annotated Copy of The History of King Lear, an Adaptation by Nahum Tate.” British Library, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/david-garricks-annotated-copy-of-the-history-of-king- lear-an-adaptation-by-nahum-tate.

Dryden, John, 1631-1700. Notes and Observations on the Empress of Morocco, Or, some Few Errata’s to be Printed Instead of the Sculptures with the Second Edition of that Play. , 1674. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/notes-observations-on-empress-morocco-some-few/docview/2248541949/se-2.

Eusden, Laurence. A poem on the marriage of His Grace the Duke of Newcastle to the Right Honourable the Lady Henrietta Godolphin, inscrib’d to His Grace. By Mr. Eusden. 2nd ed., printed for J. Tonson, at Shakespear’s-Head over-against Katharine-Street in the Strand, 1717. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0111229192/ECCO?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=0227d16a&pg=1.

Eusden, Laurence. The royal family! A letter to Mr. Addison, on the King’s accession to the throne. By Mr. Eusden. London: printed for J. Tonson: and re-printed and sold by E. Waters in Essex-Street, 1714. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0124763008/ECCO?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=a0ac1c67&pg=1.

Eusden, Laurence. Verses at the Last Publick Commencement at Cambridge. Written and spoken by Mr. Eusden. 2nd ed., printed for J. Tonson, at Shakespear’s-Head over-against Catherine-Street in the Strand, 1714. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0113597967/ECCO?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=1e83603a&pg=1.

Fielding, Henry. The Author’s Farce: With a Puppet-show, Call’d The Pleasures of the Town. As Acted at the Theatre Royal in Drury-Lane. Written by Henry Fielding, Esq. United Kingdom, J. Watts, 1750.

Kent, William, “Head-Piece to Book III of Pope’s ‘The Dunciad,’” 1735. From The Works of Mr. Alexander Pope. Vol. II, London: Lawton Gilliver, 1735. Royal Academy of Arts, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/head-piece-to-book-iii-of-popes-the-dunciad.

Koon, Helene. “Eliza Haywood and the ‘Female Spectator.’” Huntington Library Quarterly, vol. 42, no. 1, 1978, pp. 43–55. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3817409. Accessed 3 Mar. 2023.

“News.” Grub Street Journal, 21 Jan. 1731. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Burney Newspapers Collection, link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/apps/doc/Z2000495515/BBCN?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-BBCN&xid=265a9566. Accessed 6 Apr. 2023.

Nichols, J. & Co. Fig. 3. “The Duke’s Theater, Dorset Gardens [graphic].” The Folger Shakespeare. July 1, 1814. https://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/detail/FOLGERCM1~6~6~42486~103030:The-empress-of-Morocco%25C2%25B7-A-tragedy–?qvq=q:empress%20of%20morocco&mi=3&trs=7.

Nicholas, Brady, and Tate, Nahum. A New Version of the Psalms of David, Fitted to the Tunes Used in Churches. London: Printed by M. Clark, for the Company of Stationers, 1696. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/newversal00brad/page/n5/mode/2up. Accessed 2 Mar. 2023.

Ovid. Ovid’s Metamorphoses, in fifteen books. Translated by Mr. Dryden. Mr. Addison. Dr. Garth. Mr. Mainwaring. Mr. Congreve. Mr. Rowe. Mr. Pope. Mr. Gay. Mr. Eusden. Mr. Croxall. And other eminent hands. Publish’d by Sir Samuel Garth, M.D. Adorn’d with sculptures. … 2nd ed., vol. 2, printed for J. Tonson: and sold by J. Brotherton and W. Meadows, at the Black Bull in Cornhill, MDCCXX. [1720]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0114237941/ECCO?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=0eaf2e3a&pg=4.

Pope, Alexander. Alexander Pope: The Major Works. New York, Oxford University Press Inc., 2008.

Pope, Alexander. The Poems of Alexander Pope : A One-Volume Edition of the Twickenham Text with Selected Annotations. Edited by John Butt, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1973, pp. 317–459, 709–805.

Richardson, Jonathan. Portrait of Laurence Eusden, 1720.

Sambrook, James. “Eusden, Laurence (1688–1730), poet.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23. Oxford University Press. Date of access 9 Feb. 2023, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-8934.

Settle, Elkanah, 1648-1724. Notes and Observations on the Empress of Morocco Revised with some Few Errata’s to be Printed Instead of the Postscript, with the Next Edition of the Conquest of Granada. , 1674. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/notes-observations-on-empress-morocco-revised/docview/2240954374/se-2

Settle, Elkanah. Fig 2. “The empress of Morocco· A tragedy. With sculptures. As it is acted at the Duke’s Theatre. Written by Elkanah Settle, servant to his Majesty.” The Folger Shakespeare. 1673. https://luna.folger.edu/luna/servlet/detail/FOLGERCM1~6~6~42486~103030:The-empress-of-Morocco%25C2%25B7-A-tragedy–?qvq=q:empress%20of%20morocco&mi=3&trs=7#

Settle, Elkanah, 1648-1724. The Empress of Morocco a Tragedy, it is Acted at the King’s Theatre / Written by Elkanah Settle. , 1698. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/books/empress-morocco-tragedy-is-acted-at-kings-theatre/docview/2240953168/se-2.

Spencer, Christopher. Nahum Tate. New York, Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1972.

Tate, Nahum. “An Ode Upon His Majesty’s Birth-Day. Newberry Library, 1693. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/case_6a_159_no_23/page/n1/mode/2up. Accessed 6 April 2023.

Tate, Nahum. While Shepherds Watched Their Flocks by Night. Boston: D. Lothrop and Company, 1886. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/whileshepherdsw00hngoog/page/n8/mode/2up. Accessed 2 Mar. 2023.

The Dunciad. London: N.p. Print.

Williams, Abigail. “Settle, Elkanah (1648–1724), playwright.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 04. Oxford University Press. Date of access 2 Mar. 2023, https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-25128

Williams, Sheila. Fig 1. “The Pope-Burning Processions of 1679, 1680 and 1681.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 21, no. 1/2, 1958, pp. 104–18. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/750489. Accessed 6 Apr. 2023.