Far from being the greatest poets on the shelves or the greatest dramatists on the stage, the following individuals found their greatest triumphs in writing literary criticism. Unfortunately for them, these triumphs could not save their legacies from the sharpest satirical wits of the age, the Scriblerians. What follows is a clash between two classes of writers (namely poets and critics) who each held vastly different definitions of literary success.

John Dennis (1657-1734), poet, dramatist, and literary critic

John Dennis held the gaze of early eighteenth-century English society for over three decades. Although Dennis wrote some plays and poems, his literary criticisms earned him the most success. His long-standing reputation granted him power over public opinion as well as won him enemies. In retrospect, we remember Dennis best as the rival of Alexander Pope and the target of the poet’s ruthless farce.

The public feud between Dennis and Pope endured nearly two decades, the majority of Dennis’ career. No censure was off-limits, extending from criticism of individual works to jabs as his physical appearance, artistic ability, politics, morality, social status, and even the intellect of his supporters. Their feud began in 1711 with Pope’s publication of An Essay on Criticism, in which he dissed a failed play by Dennis, who came to his own public defense. With the release of every new work the two writers grew more merciless in their attacks, consistently blasting each other for seven years. Over the course of their correspondence, alliances formed. The rivalry became a war. In 1717 Dennis published Remarks Upon Mr. Pope’s Translation of Homer, which seemingly lulled Pope to rest. Ten years of quiet passed while Pope subscribed to Dennis’ work. Still reeling, Pope released Peri Bathous, or the Art of Sinking in Poetry in 1727 and then in the following year The Dunciad, his cruel magnum opus.

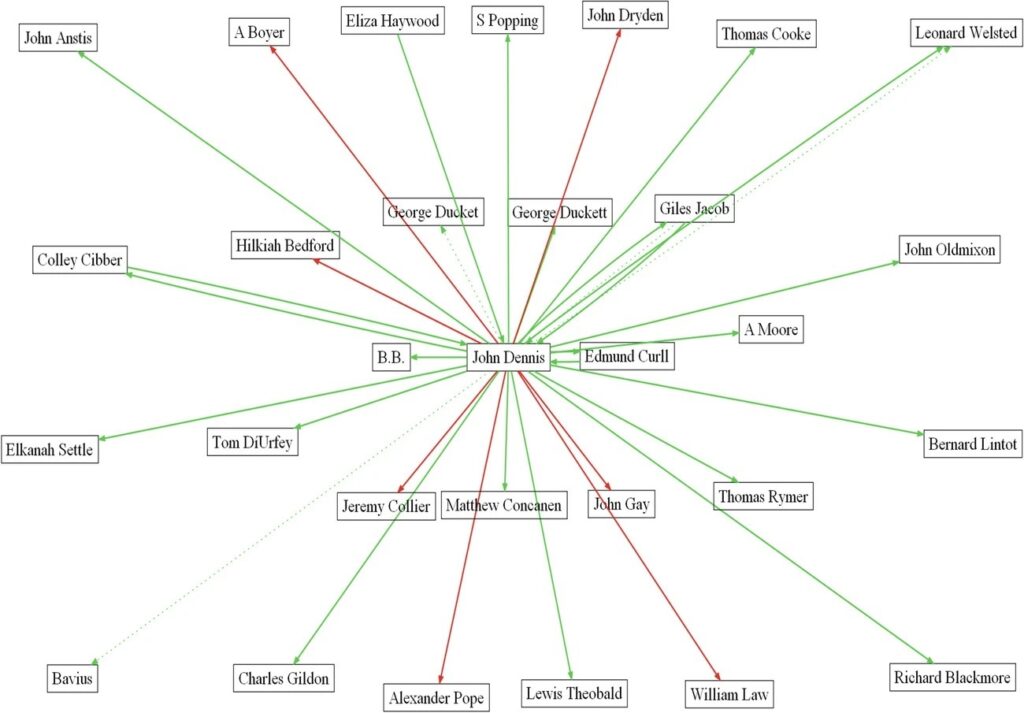

The Dunciad culminated Pope’s dissension. Dennis was connection to many relevant literary figures, whom Pope dubbed Dunces. His allies thus became Pope’s enemies. Pope attacked Dennis in The Dunciad with a total of 92 references, making Dennis his central target, as he was in public life. Pope showcased him in three Dunciad Illustrations, more than any other Dunce, and mentioned him eight times alone in the List of Abusers in Appendix II. The epic centralized Dennis through these many recurrences.

“But Fool with Fool is Barb’rous Civil War” (Pope, Book III, 170)

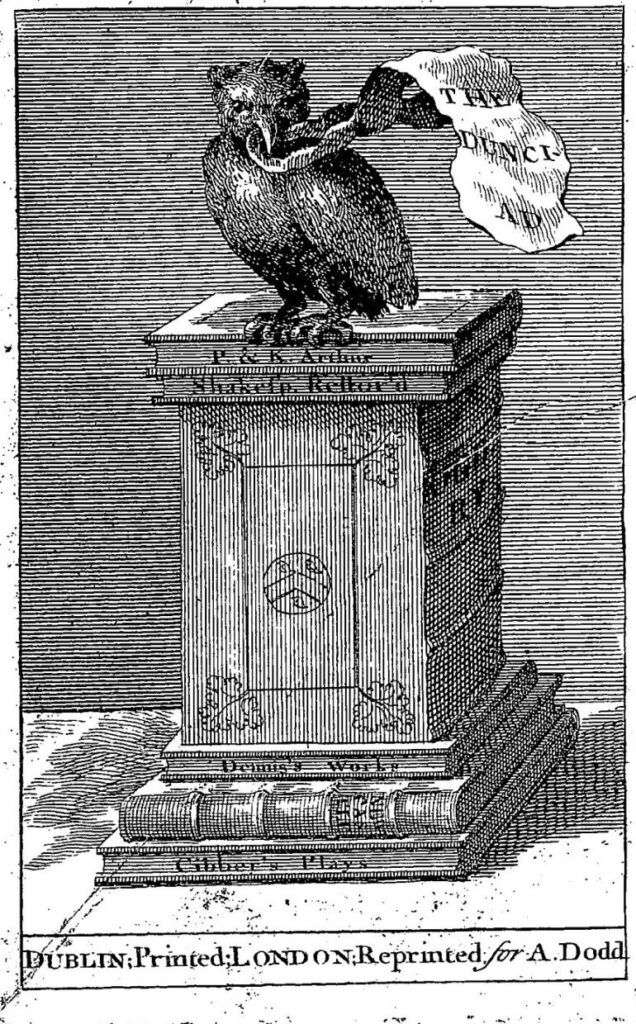

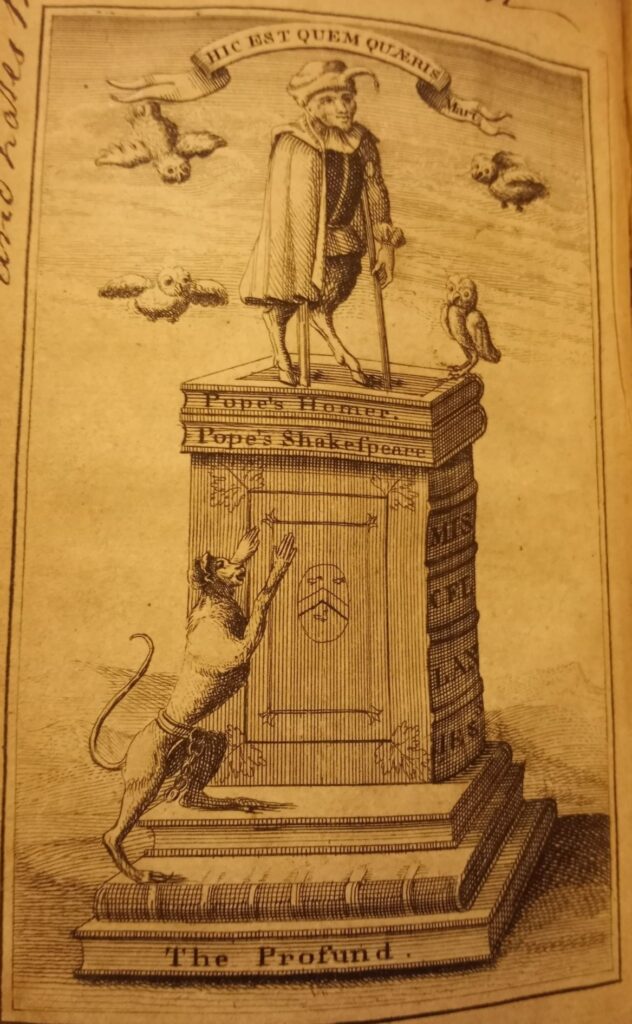

Throughout their rivalry, each recycled criticisms leveled at them, echoing each other. Pope’s growing influence and popularity particularly troubled Dennis. Pope built a reputation, consequently wielding power to shape others in his image. For Dennis, power in the hands of misfits like Pope, meant the ruin of society. Both Dennis and Pope mirrored each other’s modes of attack and perpetuated a vicious cycle, as demonstrated by these similar frontispieces. They despised one another, yet oddly expressed themselves in the same manner.

Pope presented a recurring argument that the Critic not only held a tyrannical and unnecessary profession but suffered artistic impotence. Since none of their creations were sufficiently sublime, the Critic was resigned to celebrate or condemn the works of others. These attitudes spilled over in the Dunciad and were at the core of their paper wars.

Lewis Theobald (1688-1744), editor, translator, and author

Despite beginning his career as an upstart poet and dramatist, Lewis Theobald ultimately found success by aligning himself with Shakespeare’s rising brand. His unwavering commitment and personal devotion to The Bard’s legacy secured his place as one of the early eighteenth century’s most prominent textual critics of Shakespeare.

The publication of Shakespeare Restored in 1726 marked Theobald’s first book-length, critical treatment of Shakespeare’s dramatic works. As a work of textual criticism, the book was notable for its use of “conjectural emendations,” which consisted of speculative textual improvements that held no precedent in either the First Folio or Quarto editions of Shakespeare. These kinds of improvements, while controversial at the time, effectively turned the editor into a textual critic. For Theobald, the application of conjectural emendations became a way of resolving the blunders of preceding editors and advancing, as the work’s title page boldly declared, a “True reading of SHAKESPEARE.”

With such grandiose self-proclamations of textual legitimacy, Shakespeare Restored provoked just as much as it “restored.” Its meticulous, line-by-line emendation of Alexander Pope’s 1725 edition of The Works of Shakespear (specifically his Hamlet) fueled personal tensions between the two editors and made Theobald a prime target for the Scriblerus Club’s mockery. Pope’s publication of The Dunciad Variorum in 1729 brought this fierce rivalry center stage with its satirical representation of “Tibbald” as the newly-crowned “King of Dulness.” As the poem’s mock-epic hero, Theobald surfaces as a “monster-breeding” poet and a pedantic critic who “[crucifies] poor Shakespear once a week” with his textual emendations (Book I, 106, 164). These kinds of personal insults reveal a resentment on Pope’s part for individuals like Theobald who, having fallen short of their poetic ambitions, sought fame and influence in the emerging field of criticism.

Theobald’s objective of completing a full textual “restoration” of Shakespeare’s plays eventually culminated in The Works of Shakespeare, a seven-volume work published in 1733. This edition directly challenged Pope’s 1725 Shakespear while also establishing its own textual authority over all preceding editions. For Theobald, achieving this authority meant achieving a new kind of prestige as a textual critic. But as the Shakespeare engraving in the work’s frontispiece shows, the critic’s name was inseparable from the image of the critical subject. In this way, Theobald’s efforts to achieve public renown for himself through criticism simultaneously elevated Shakespeare’s status in eighteenth-century literary society.

Richard Bentley (1662-1742), classical scholar

Posterity recalls Richard Bentley as a classical scholar and philologist but rarely acknowledges him as the formidable textual critic he was. As early as 1713, Bentley’s academic research allowed him to realize “that hundreds of hiatuses would disappear if the obsolete digamma (pronounced as ‘w’) were restored” to Homer’s texts. His important discovery, however, went “unappreciated until the nineteenth century” (Quehen). Unfortunately, Bentley’s death in 1742 prevented him from ever completing his restoration project.

Like Theobald, Bentley used conjectural emendations to shape his 1711 edition of Horace and the 1732 edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost. During the construction of his Horace, Bentley spent “less than a year for the text, but nearly seven for the textual notes” (Quehen). Predictably, the book faced “much [condemnation] for the great Liberty [Bentley] hath taken in altering the text” and “his Criticisms [were] also much despised” (Hearne, 295-296). Bentley continued to parade his critical audacity with his Milton, making “800 emendations in the margin (plus some seventy expulsions of text in brackets) [along with] notes defending this virtual rewriting” (Quehen). Bentley’s Milton also assisted in stimulating Pope’s ire toward critics as a species.

Pope displays this hatred for critics, and for Bentley in particular, within his “Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot.” He claims that though he could “[slash] Bentley down” (Line 164), Bentley would remain “preserved in Milton’s… name” (Line 168). Ironically, Pope’s disdain for Bentley culminates in the inclusion of the critic within Pope’s 1742 edition of The Dunciad, ultimately preserving Bentley far better than his fairly mediocre edition of Milton ever could.

The Dunciad refers to Bentley as Aristarchus, an ancient Greek grammarian notable for his influence on Homeric poetry. Pope hails Bentley/Aristarchus as a “mighty scholiast” (Book IV, Line 211) who “made Horace dull, and humbled Milton’s strains” (Book IV, Line 212). Pope did not limit himself to attacks against Bentley’s critical endeavors. He also mocked Bentley’s scholarly pursuits, referring to him as the “author of something yet more great than Letter” (Book IV, Line 216) who “[towers] o’er [his] Alphabet, like Saul” (Book IV, Line 217) and whose Digamma stands “o’er-tops them all” (Book IV, Line 218). Within the notoriously sarcastic footnotes of The Dunciad, Pope writes “the neglect of a Single Letter [is not] so trivial as to some it may appear” (719). The Dunciad solidifies Bentley as a nitpicking dunce—unskilled in scholarship, philology, or criticism—who ought to be forgotten by posterity altogether. Ironically, The Dunciad has preserved Bentley’s influence.

Sources Consulted

Baird, I. Fig. 2. Outliers, Connectors, and Textual Periphery: John Dennis’s Social Network in The Dunciad in Four Books. In: Baird, I. (eds) Data Visualization in Enlightenment Literature and Culture. (2021). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. Accessed 2 April 2023. John Dennis’s Social Network in The Dunciad in Four Books

Dennis, John, Concanen, and (Matthew) Concanen. Fig. 4. A Compleat Collection of All the Verses, Essays, Letters and Advertisements, Which Have Been Occasioned by the Publication of Three Volumes of Miscellanies, by Pope and Company. : To Which Is Added an Exact List of the Lords, Ladies, Gentlemen and Others, Who Have Been Abused in Those Volumes. With a Large Dedication to the Author of the Dunciad, Containing Some Animadversions Upon That Extraordinary Performance. London;: Printed for A. Moore …, 1728., 1728. Print.

Dennis, John. Reflections critical and satyrical, upon a late rhapsody call’d, An essay upon criticism. Printed for Bernard Lintott, at the Cross Keys between the Two Temple-Gates in Fleetstreet, [1711]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Accessed 4 Mar. 2023

Faithorne, William. Fig. 11. Frontispiece to Richard Bentley’s edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost. 1720. The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1874-0613-1439. Accessed 5 Apr. 2023.

Goeree, Jan. Fig. 10. Frontispiece to Richard Bentley’s edition of Horace. 1713. The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1901-1022-1953. Accessed 5 Apr. 2023.

Hearne, Thomas. Remarks and Collections of Thomas Hearne. Edited by C.E. Doble, vol. 3, Clarendon Press, 1889.

Pope, Alexander. An Essay on Criticism. 2nd ed., printed for W. Lewis in Russel-Street Covent-Garden, MDCCXIII. (1712). Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Accessed 4 Apr.. 2023.

Pope, Alexander. The critical specimen London, 1711. Accessed 4 Apr. 2023, The critical specimen. (nla.gov.au)

Pope, Alexander. Fig. 12. The dunciad, in four books. Printed according to the complete copy found in the year 1742. With the prolegomena of scriblerus, and notes variorum. To which are added, several notes now first publish’d, the hypercritics of aristarchus, and his dissertation on the hero of the poem. Printed for M. Cooper at the Globe in Pater-noster-row, 1743. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CB0129514452/ECCO?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=76bfd2b4&pg=181. Accessed 5 Apr. 2023.

Pope, Alexander. The Dunciad. An heroic poem. In three books. Dublin, printed, London re-printed for A. Dodd, 1728. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CB0126231877/ECCO?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=f0f8688a&pg=1. Accessed 30 Mar. 2023.

Pope, Alexander. Fig. 3. The Dunciad, variorum. With the prolegomena of Scriblerus. London: printed and reprinted, for the booksellers in Dublin, 1729. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0124760396/ECCO?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=de43ff88&pg=1. Accessed 30 Mar. 2023.

Pope, Alexander. The Poems of Alexander Pope. Edited by John Butt, Yale University Press, 1963.

Pope, Alexander. The Poems of Alexander Pope: One-Volume Edition of the Twickenham Text with Selected Annotation. Edited by John Butt. New Haven Yale University Press, 1977. Print.

Quehen, Hugh. “Bentley, Richard (1662–1742), philologist and classical scholar.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004, <https://www-oxforddnb-com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-2169>. Accessed 1 Mar. 2023.Thornhill, James. Richard Bentley. 1710. NPG, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitExtended/mw00527/Richard-Bentley?LinkID=mp00385&search=sas&sText=richard+bentley&role=sit&rNo=0. Accessed 1 Mar. 2023.

Swift, Jonathan. Fig. Featured Image. A tale of a tub. Written for the universal improvement of mankind. To which is added, an account of a battel between the antient and modern books in St. James’s Library. 5th ed., Printed for John Nutt, near Stationers-Hall, 1710. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CB0131107112/ECCO?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=8fd995e3&pg=280. Accessed 7 Apr. 2023.

Thornhill, James. Fig. 9. Richard Bentley. 1710. NPG, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitExtended/mw00527/Richard-Bentley?LinkID=mp00385&search=sas&sText=richard+bentley&role=sit&rNo=0. Accessed 1 Mar. 2023.

Theobald, Lewis. Shakespeare restored…London: printed [by Samuel Aris] for R. Francklin under Tom’s, J. Woodman and D. Lyon under Will’s, Covent-Garden, and C. Davis in Hatton-Garden, M.DCC.XXVI. [1726]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/apps/doc/CW0111313813/ECCO?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=1328c510&pg=1.

Theobald, Lewis, ed. Shakespeare, William. The works of Shakespeare in seven volumes. London: printed for A. Bettesworth and C. Hitch, J. Tonson, F. Clay, W. Feales, and R. Wellington, MDCCXXXIII. [1733]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/apps/doc/CW0110267340/ECCO?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-ECCO&xid=adee7db3&pg=503.

Vandergucht, John. Fig. 1. John Dennis line engraving. 1734. National Portrait Gallery, London. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp15111/john-dennis?search=sas&sText=john+dennis . Accessed 2 April 2023.