In my classroom at The University of Texas at Austin, I teach a relatively new class called Design Pedagogy – aka the methods and practice of teaching design. We have a mix of MFA design students and students pursuing graduate degrees in higher education. According to the University catalog, all students are supposed to spend six hours engaged in “asynchronous learning” outside of class, in addition to the three hours we spend together during pre-scheduled class time.

What is asynchronous learning?

Time (not duration) and place of learning are the units of analysis for asynchronous instruction. Students have the autonomy to choose when they learn and where they learn. Synchronous learning, on the other hand, is learning that happens at a predetermined, specific time and place – with no choice. Here’s a quick contrasting case explaining the differences.

What are the benefits of asynchronous learning?

There are several, however, in my opinion, the biggest benefit is that asynchronous learning affords autonomy, and more specifically autonomy of choice. In the case of learning – students can choose when to learn, where to learn, and often how (the path they will follow, long they will spend on a task, etc). Autonomy is a potent motivator of human behavior and has a host of benefits including greater well-being and academic achievement in schools ( Deci et al. (1991).

Asynchronous learning is not new.

Asynchronous learning is a newish phrase for an age-old concept. I was born and raised in Las Vegas, so I always like a friendly bet. And, I would wager that everyone reading this post and everyone they know, and everyone they know has engaged in substantial asynchronous learning throughout their lives vis a viz doing homework.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines homework as “schoolwork assigned to a pupil to be done outside lesson time (typically at home). In extended use: An assignment or exercise to be completed in one’s own time.” Homework is the most basic form of asynchronous learning.

Asynchronous learning needs as much attention as synchronous learning.

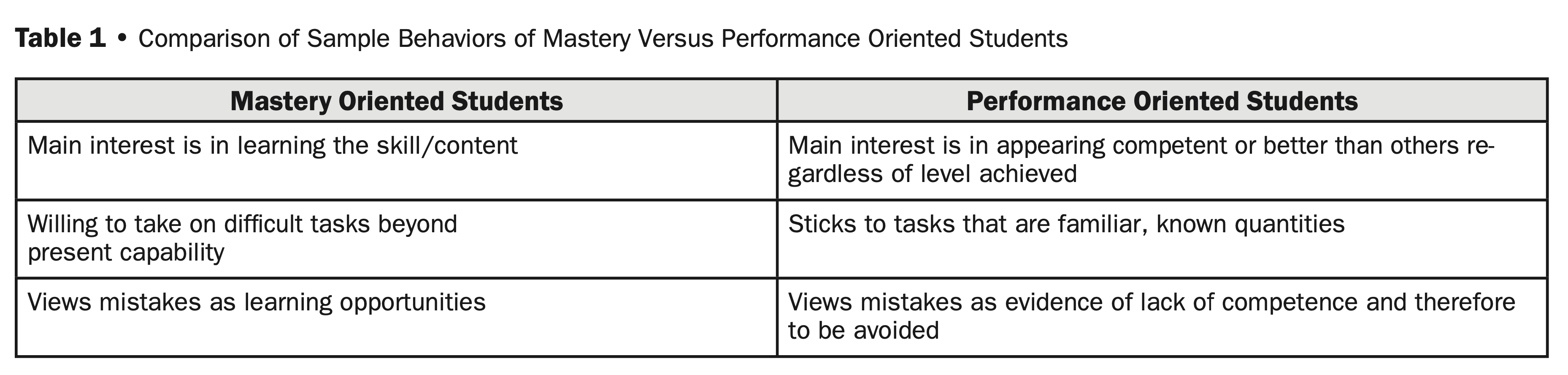

For most college students, homework is about as enjoyable as a plate of boiled Brussel sprouts. Homework is generally something that you do on your own, and it is most often a hoop to jump through. Performance orientated students won’t do it unless it counts toward a grade, and mastery orientated students need more than a few boxes to tick off (see Svinicki, 2005).

During the Fall of 2020, I put as much effort into my asynchronous design as my synchronous course design. Other educators, such as my post-doc advisor Eric Mazur, are doing the same. And we are both finding that contrary to popular belief – students are engaged and doing their “homework” when instructors put thought and effort into their asynchronous designs.

A Framework for Asynchronous Learning: Explore, Collaborate, Retrieve

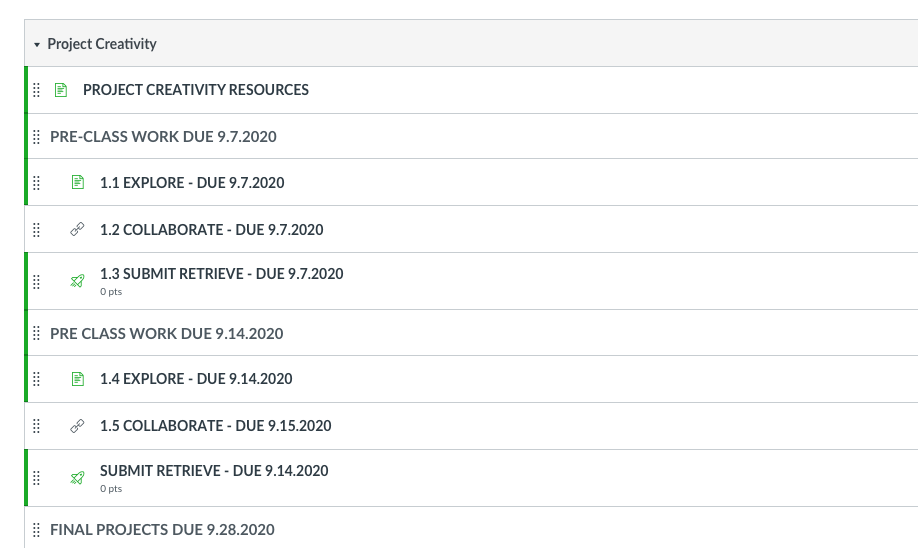

My asynchronous framework involved a learning path with three distinct stops that students visited before very class:

Explore: Students explored key content, always with an element of choice, autonomy, and freedom.

Collaborate: Students constructed knowledge in a community of inquiry with their peers and me using Persuall.

Retrieve: Students retrieved content from memory via Canvas quizzes.

Students navigated through the learning path in Canvas with clearly indicated deadlines, as shown in this screenshot.

Why use a framework to plan asynchronous learning activities?

According to asynchronous learning researchers, ” when online students are presented with an easy-to-read and feasible timeline of tasks to complete, their locus of control increases, enabling them to tackle and complete one thing at a time.” It also saves me a ton of time to have a template for planning course activities. Whether it’s Explore, Collaborate, Retrieve, or any other framework – I recommend using a consistent structure for students when designing asynchronous work. Structure and consistency are soothing and will make the “homework” more appealing for all of us.

Leave a Reply