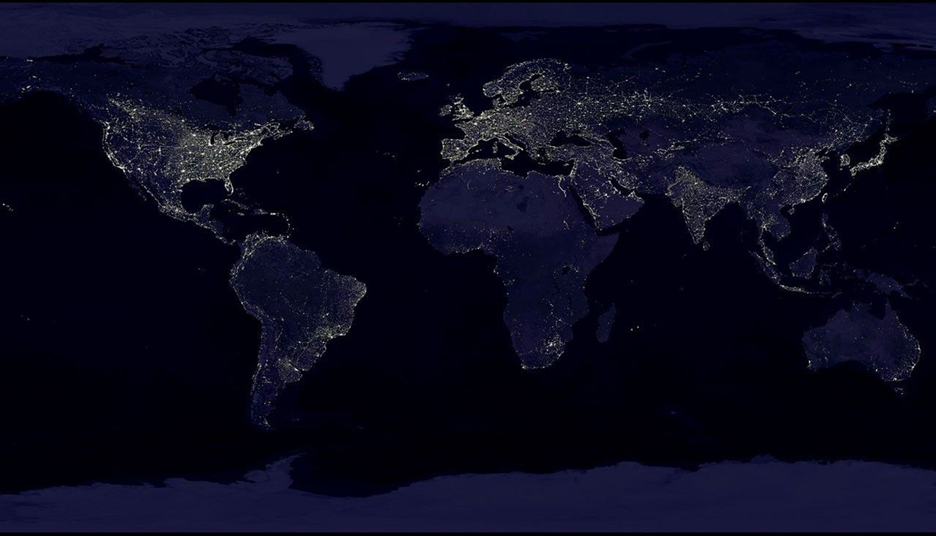

A view of nighttime lights from NASA/NOAA. https://science.nasa.gov/resource/earth-atnight/

By Chloe Fisher, F24 Environmental Clinic Student

With fossil fuel emissions driving climate change and the effects of climate change becoming reality, rather than conjecture, reducing our global carbon footprint is more important than ever for the health of our planet and its inhabitants. Climate change is likely to cause significant physical and financial destruction within our lifetime. And the people who are likely to shoulder the largest burden of climate destruction are the poor and impoverished. However, it is also the poor and impoverished that are more likely to experience energy poverty.

According to a recent paper from Science Direct, 1.18 billion people live in energy poverty across the developing world and 733 million people live without any electricity connection at all. Given these figures, we can see why poorer nations are adamant that they will electrify. For example, India has seen energy consumption more than double since 2000, coinciding with a period of rapid population and economic growth. After all, economic growth has a strong positive relationship with increased consumption of energy.

This brings us to a glaring challenge for a just transition: ensuring the rapid development and use of low-carbon technologies and the 1.18 billion people living in energy poverty who desire cheap, accessible energy. According to an article from Brookings, the most reliable and energy dense energy is from fossil fuels.

Therefore, to facilitate a just transition, we must simultaneously address the need to decarbonize and the need for global energy security. I posit the following possible solutions: (1) focusing decarbonization efforts on wealthier countries and (2) making clean energy cheap.

First, focusing on decarbonization in wealthier countries would benefit the goals of a just transition by targeting the largest emitters per capita, while leaving developing countries to focus on the immediate needs of their people. For example, Canada’s tax on luxury items, like certain vehicles and aircrafts, is a successful initiative that places the burden of decarbonization first and foremost on those both responsible for the most emissions and capable of absorbing the economic costs associated with decarbonization. This proposal is in contrast with ideas that wealthier countries should significantly interfere with the energy goals of developing countries, stifling their progress towards energy

security.

Second, making clean energy cheap would advance a just transition by providing both the benefits of keeping emissions down and bringing energy security to developing countries. According to a recent paper from Science Direct, the way to facilitate cheap, clean energy is likely focusing on innovation in nuclear, wind, solar, and geothermal energy dispatch. The more efficient and readily available these products are, the lower their costs.

However, though these strategies may forge a path towards a just transition, the conflict between addressing the climate change and energy insecurity is likely to remain a challenge. Both issues deserve attention and care as policymakers around the globe seek to meet the needs of today, without sacrificing the needs of tomorrow.

The articles published on this site reflect the views of the individual authors only. They do not represent the views of the Environmental Clinic, The University of Texas School of Law, or The University of Texas at Austin.